When In Doubt, Stop the Bout: A Revolutionary Approach to Boxing Safety and Reform, by Mike Silver (Hamilcar Publications, 224 pp., $21.99)

While boxing can inspire lofty words such as grace, speed, courage, and power, it is, at its most basic level, soft tissue damage, blunt force trauma, subcutaneous hemorrhage, and subdural hematoma. The logical outcome of two trained athletes exchanging precise, deliberate blows is injury—and that more fighters are not maimed from their exertions reflects their remarkable physical conditioning and skill. Even so, as the most hazardous sport in America, boxing corrodes the past, present, and future of its participants simultaneously. In an extended career, the physical punishment from sparring, training, and fighting inevitably leads to damage of one kind or another. Most fighters face a retirement marked by neurological deterioration (including, in the worst-case scenario, CTE) and markedly reduced circumstances. Some of the greatest fighters, despite lucrative ring earnings, wound up living the harrowing posthumous existence triggered by what was once known as pugilistic dementia. A (very) short list of these once-celebrated athletes includes icons such as Muhammad Ali, Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson, and Mickey Walker. And these tragic after-effects exclude the specter of death and incapacitation that looms over every match.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

In When in Doubt, Stop the Bout, veteran writer and historian Mike Silver tackles the question of boxing safety in what amounts to a quixotic pursuit in 2025. After all, boxing is no longer an established part of the American sports-pop purview, as it was for much of the twentieth century. Where boxing was once used by network television to counterprogram prestige events such as the U.S. Open and even NCAA basketball during sweeps season, it is now relegated to the often-confusing world of apps.

Despite its disappearance from the public eye, organized boxing, notwithstanding its development in regency England, is a uniquely American pursuit, underscoring themes of exceptionalism, individualism, and egalitarianism. Theoretically, the ring is a level playing field where hereditary advantages are meaningless and fighters forge their own destinies. This, to some extent, explains its brute appeal, yet boxing has slipped so far from its past heights that not even the bootstrap narrative appeals as it once did. These days, boxing strikes some as a barbaric anachronism, even as other disagreeable pursuits thrive: mixed martial arts, bareknuckle fighting, and the unholy Power Slap. Boxers still die in the ring—two on the same card in Japan recently died, after separate bouts—but in the United States, at least, fewer participants mean a much lower casualty rate.

As with many longtime observers, Silver, once an inspector at the New York State Athletic Commission, eventually gave up on boxing altogether. His 2008 jeremiad, The Arc of Boxing, outlined in almost perverse hyper-detail the decline of a sport once second only to baseball in popularity. The fight aficionado of Silver’s imagination once dined regularly on chateaubriand steak and mousse of sole while today, the uninformed hoi polloi are gorging themselves on C-rations or White Castle sliders.

Some of what Silver proposes in When in Doubt, Stop the Bout is offbeat, to say the least, and tinged by his view of boxing being in a terminal decline. At times, in fact, Silver seems to use safety as a pretext to excoriate the modern iteration of a sport he used to love; as a result, he often sounds like an abolitionist. Indeed, if there is one route to finally eradicating boxing in America, it would be to implement his suggestions across the board. A theoretical bout under the Silver Safety Protocols would be a six-rounder between two pros with a combined 40 fights. There would be a standing eight-count (implemented and abandoned in several jurisdictions over the past few decades), two doctors at ringside with air horns, headgear worn by each participant, and a slew of new rules concerning mouthpieces, taking a knee mid-fight, and scoring.

Other suggestions seem like pipedreams. For example, Silver calls for a global overhaul of boxing, an idea not only dubious but also logistically, culturally, and politically impossible. While regulatory oversight is lax in a North American stronghold such as Mexico, it’s virtually nonexistent in some Asian countries, such as Thailand, where leading fighters often square off against non-pugilists making their pro debuts.

One of Silver’s main theses in When in Doubt, Stop the Bout is that boxing is more dangerous now (due to the ineptitude of contemporary professionals and longer bouts) than it was during its golden age, which Silver defines as roughly stretching from the 1920s to the early to mid-1970s. In outlining the lethality of boxing, Silver relies primarily on statistics from 1980 to 2020. Unfortunately, he fails to produce fatality statistics from, say, 1940 to 1980 for comparative purposes, seriously undermining his argument. Another questionable claim concerns CTE. Using anecdotal evidence, Silver has arbitrarily decided that contemporary fighters suffer from CTE at higher rates than those from his beloved golden age. We do not, in fact, know if CTE is more prevalent today; CTE can only be diagnosed postmortem.

Though he sketches a few contemporary tragedies, Silver saves his ire for case studies from decades ago, as if nothing has changed since 1980, when a woefully unfit Muhammad Ali took a brutal beating from a young Larry Holmes in a fight that should never have been staged. Silver devotes several paragraphs to the Holmes–Ali fiasco, though it has been autopsied over the last 40 years in newspapers, books, and documentaries. Similarly, extended passages on Kim Duk-koo (killed in the ring by Ray Mancini in 1982), Willie Classen (killed in the ring by Wilford Scypion in 1979), and promoter Don King, now 94 and a nonfactor in boxing for nearly 20 years, are outdated, especially since Silver is not writing an historical overview of fatalities and injuries.

Much has changed since the early 1980s, when the American Medical Association, in response to the deaths of Kim Duk-koo and Johnny Owen, made a concerted effort to ban boxing. Joining the AMA were various high-profile media figures, including George Vescey of the New York Times and Frank Deford of Sports Illustrated, both openly contemptuous of the sport. (Boxing being boxing, Deford sometimes appeared as a pay-per-view host for big-ticket fights, offering hackneyed commentary about a sport he supposedly abhorred, at least once with a Collins glass in hand.) Most famously, perhaps, Howard Cosell, audibly disgusted while working the blow-by-blow call of the Larry Holmes–Tex Cobb mismatch on ABC in 1982, quit as ringside commentator a few days after the fight.

Title fights are no longer 15 rounds, most state commissions require a minimum number of physicians at ringside, and thumbless gloves, introduced in the early 1980s, reduce detached retinas, once a major occupational hazard for fighters. Weigh-ins are now held a day before the fight, allowing weakened fighters 24 hours to rehydrate. Though this has the negative effect of allowing fighters to blow up to unnatural weights by the time the opening bell rings, it remains, to some degree, an advantage exploited by all boxers. Curiously, while Silver points out that dehydration is a significant if not yet fully understood risk for boxers, he nevertheless favors the return of same-day weigh-ins.

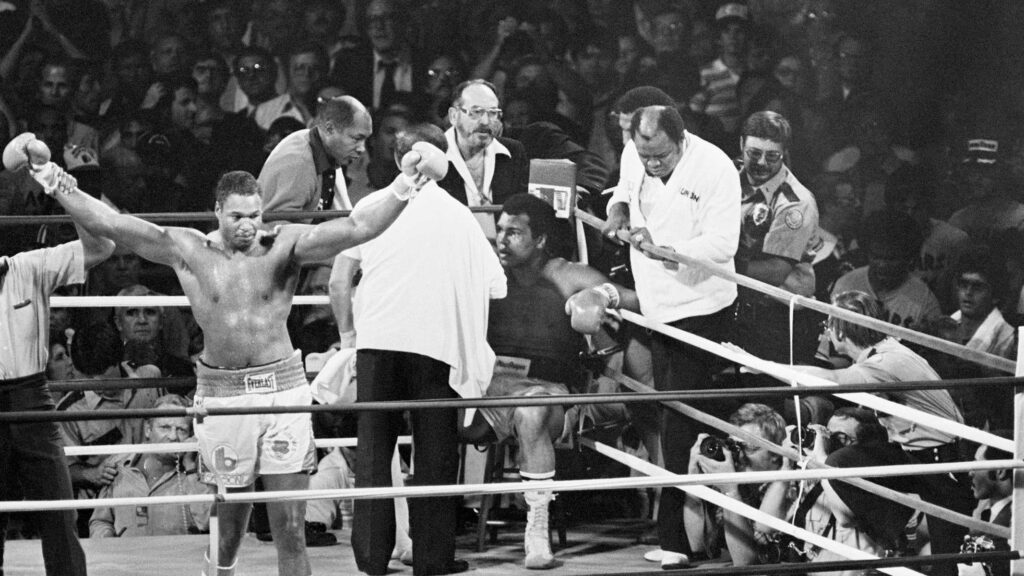

Boxing has become, in general, far more merciful since the Golden Age. Until the 1950s, or thereabouts, a referee would often terminate a contest if he deemed it insufficiently violent. No longer will the bloodthirsty be able to see massacres such as 1959’s Ingemar Johansson–Floyd Patterson I (where Patterson suffered seven knockdowns before Referee Ruby Goldstein finally halted the bout) or 1973’s George Foreman–Joe Frazier I (where Frazier hit the canvas six times), much less the pathetic 1953 showing on live television of Tommy Collins, battered to the deck ten times by lightweight champion James Carter in just a few rounds. As for legendary fights from bygone times, the gory Jack Dempsey–Jess Willard bout (the infamous 1919 massacre under the sun), is unimaginable today; ditto the hell-on-earth, early-twentieth-century brawls featuring Battling Nelson and Ad Wolgast, in which both men were irreparably damaged. In addition, fighters no longer perform every two or three weeks, as they often did in the twenties, thirties, and forties; instead, they enter the ring on a yearly basis, preserving themselves physically while simultaneously limiting their skills and marketability. (Not surprisingly, Silver is not so sure that fighting twice a year is safer than fighting 20 times a year.)

As in The Arc of Boxing, Silver reserves most of his ire for the notorious sanctioning bodies—self-interested, self-appointed governing organizations that rank fighters, crown champions, and cause all sorts of administrative havoc to a sport whose (theoretical) simplicity is part of its appeal. This is where Silver is at his best: fulminating against the institutionalized rot of an industry with little oversight and few scruples. According to Silver, the peripheral figures and entities involved in boxing—physicians, judges, managers, referees, promoters, trainers—are, with rare exceptions, either scoundrels or nincompoops. Even state athletic commissions, which function as de facto regulatory boards within their jurisdictions, are overrun by blockheads. “The boxing commissions serve an essential role,” writes Silver, “but their effectiveness is often compromised by bureaucratic inefficiency and incompetence. State boxing commissioners are frequently appointed not for their expertise in boxing but rather because of political patronage, as governors often use these positions to repay political favors. This often results in poor governance and oversight of the sport.”

The sanctioning bodies are transparently corrupt and unregulated. Anybody can start one, as history bears out with near-surrealist aplomb. In 1981, an Oklahoma scamp named Pat O’Grady founded the WAA after his son Sean O’Grady was stripped of the WBC lightweight title. Pat promptly installed Sean as the first WAA champion, a distinction on par with being the inaugural winner of the International Pancake Race. Then, he named his son-in-law, Monte Masters, WAA heavyweight champion. It was a short-lived reign for Masters, who was stripped of his designation when he divorced O’Grady’s daughter.

Today, the four major sanctioning bodies are the WBC, the WBA, the IBF, and the WBO, collectively and derisively known as the Alphabets. By manufacturing synthetic titles with the speed and efficiency of an assembly line, they have produced an atmosphere where most broadcast fights are contested for some overblown designation. Of course, billing a match as a “championship bout” is a trick as old as boxing itself, and its original intent—to bamboozle marks unfamiliar with the flimflam world of prizefighting—is only partially extant today. The marks remain, of course, now on a mass scale across global media platforms, but the true beneficiaries of these titles are the fighters, whose purses rise exponentially after winning one, and, especially, the sanctioning bodies themselves.

“Limited to one champion for each weight division, the Alphabets sought other creative ways to increase sanctioning fees,” writes Silver. “Adding more weight divisions—it was already up to seventeen from the original eight—would be too hard a sell. To circumvent this roadblock, the WBC came up with a clever innovation that the other Alphabet organizations quickly copied. What the WBC did was multiply the number of belt-holders by inventing additional titles within each of the seventeen weight categories.” The new titles were given names like “International,” “Global,” “Pan Pacific,” and “Interim.” All required a sanctioning fee from both challenger and champion for the privilege of fighting for a “title.” Even pro wrestling wouldn’t have had the nerve to create this many specious “champions.”

The sanctioning bodies are often the target of the otherwise-obsequious boxing media, which avoids criticizing promoters or television networks in hopes of maintaining access and receiving press credentials. Sanctioning bodies have no such authority over the ragtag press and as such come under withering fire from every platform imaginable.

But it is Silver who best understands the real damage these organizations do—and it goes far beyond distorting the historical record by handing out fugazi titles. These organizations make boxing more dangerous by multiplying the number of 12-round fights. Consequently, dozens of comparatively inexperienced boxers engage in fights beyond their physical capacities. Out of all the recommendations found in When in Doubt, Stop the Bout, the most sensible one is reducing the number of fights scheduled for 12 rounds. As Silver notes: “Shortening the scheduled distance for most professional boxing matches will not eliminate brain damage or even death, but it can reduce the incidence of both. Fewer rounds can save an inexperienced, exhausted, dehydrated, or overmatched boxer from additional damage that is often exacerbated by poor refereeing and inadequately trained or hesitant ringside physicians.”

Another commonsense proposal Silver offers is the adoption of a “mercy rule,” so fighters are spared prolonged beatings in fights they have little chance of winning. Confabs and calculations by ringside officials—such as Silver recommends—are unnecessary. Anyone who has witnessed a fatal match, whether from ringside or from a couch, has felt the growing sense of unease as a one-sided thrashing progresses, almost inexorably, to its tragic outcome. That a similar feeling apparently does not afflict referees or physicians is inexplicable.

While Silver makes a compelling case for the elimination of most 12-round fights, his idea of adding dozens of four-and-five-round fights to the records of most professionals is implausible because it sidesteps entirely the diminishing trajectory of boxing as a sustainable industry. Where once there were hundreds of arenas and venues across America dedicated to staging weekly prizefights, now they are as common as jai alai frontons. His recommendation of having young professionals knuckle up dozens of times in what amounts to preliminary fights (bouts scheduled for eight rounds or fewer) is similarly farfetched. Unlike in the 1920s or 1930s, when fighters might perform a dozen times a year, boxing, once a regional grassroots sport, lacks the infrastructure to add thousands of matches to an ad hoc schedule.

Silver rightly asserts that all officials—including referees, judges, and inspectors—should be adequately trained, which is not always the case in a sport as off-the-cuff as boxing. Among those in need of refresher courses are the physicians who work for the state commissions and are often incapable of recognizing faded boxers. Medical professionals, absent negative CT scans, are unable to ascertain whether a fighter poses a risk to himself because medical professionals are not in the habit of frequenting gyms; nor do they consider previous performances as a baseline to determine physical deterioration. An over-the-hill boxer is not the equivalent of a center fielder struggling with reduced bat speed or an aging NHL goalie whose reflexes have abandoned him or the three-point specialist who has lost his range from behind the arc. No, the weatherworn boxer is a man whose lack of coordination, diminished reaction time, and loss of resilience augurs possible neurological damage, if not worse.

The late Ferdie Pacheco, a physician who worked with Muhammad Ali for years, best highlighted this dilemma in an interview with Thomas Hauser: “Just because a man can pass a physical examination doesn’t mean he should be fighting in a prize ring. That shouldn’t be a hard concept to grasp. In fact, most trainers can tell you better than any neurologist in the world when a fighter is shot. You watch your fighter’s career from the time he’s a young man; watch him develop into a champion; get great; then all of a sudden, he doesn’t have it anymore. Give him a neurological examination at that point and you’ll find nothing wrong. . . . Anybody in the gym can see it before the doctors can, because the doctors, good doctors, are judging these fighters by the standards of ordinary people and the demand of ordinary jobs, and you can’t do that because these are professional fighters.”

A sometimes repetitive but informative work of advocacy (as well as bitter nostalgia), When in Doubt, Stop the Bout works best as an introduction to the labyrinthine netherworld of prizefighting, where a values-free atmosphere permeates every level. When Silver outlines how widespread incompetence and sleaze undermines safety he is irrefutably correct, as he is when he advocates for what amounts to better working conditions for boxers, who are essentially independent contractors without pensions, health insurance, and unions, and whose lives can be shattered in an instant.

Over the last year, the plight of former featherweight titleholder Heather Hardy has attracted media attention in the U.S. and overseas. Hardy, who recently sued several entities involved in her career (including the venerable glove manufacturing company Everlast), announced in October 2024 that she had retired because of brain damage sustained in the ring.

From 2012 to 2023, Hardy was a solid local attraction in the New York City area, and her shocking physical erosion, at the age of 42, reflects something about boxing that no reform can ever alter. Hardy fought two-minute rounds throughout her career, as do all female boxers (men fight three), went the ten-round distance only a handful of times, and faced a limited talent pool on her way up the ranks. Attractive, charismatic, and exciting, Hardy oozed marketability, which meant, in the often-paradoxical world of boxing, that her handlers had something like a fiduciary obligation to maintain her status as a commodity for as long as possible. Hardy fought relatively ineffectual competition until her last few years in the ring. She had fewer than 30 professional bouts. That Hardy suffers from neurological damage despite these asterisks suggests that, in the end, little could have been done to protect her. Yes, she fought too long (into her forties, a red zone for combat sports); yes, she was twice overmatched against Amanda Serrano, then one of the world’s best female fighters; and, yes, she often considered defense optional. But like many fighters impaired by boxing, she was driven by an existential need for distinction.

Boxing is not safe and never was safe. Boxing will never be safe. There is no way to regulate the overreaching desires of young men and women who risk everything for the brief transit of sporting glory. Making boxing safer means making dreams safer. Good luck with that.

Top Photo: Terrence Crawford (right) facing Canelo Alvarez in Las Vegas, September 13, 2025 (Mike Kirschbaum/TKO Worldwide LLC via Getty Images)

Source link