The Supreme Court heard arguments last week in an election case (Louisiana v. Callais) that will decide how far the federal courts can go in requiring state legislatures to consider race in drawing congressional-district lines. At issue is Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA), which prohibits voting practices that discriminate on the basis of race or membership in a language-majority group. The federal courts have cited the VRA as a basis for intervening in districting disputes to protect the interests of minority voters.

Democrats, civil-rights leaders, and their allies have claimed that a decision by the Court to eliminate race-based districting will “gut” the Voting Rights Act and thereby deprive minorities of long-standing legal protections. In truth, it will do nothing of the kind. Nevertheless, such a decision will have important consequences.

In the first place, a race-neutral decision will return the VRA to its original purpose, which was to protect access to the ballot box, especially for blacks living in previously segregated states, not to address districting issues and the like. It was a voting-rights act after all, not a congressional- or legislative- districting act. In addition, it will place all voters on an equal footing by eliminating special districts and “set-asides” for black voters, almost all of whom cast ballots for Democrats, a fact that introduces a partisan bias into the VRA that undermines its legitimacy among Republicans and independents.

Finally, a decision to ban the factoring of race into congressional districting may bring to an end a decades-long experiment in preferences and set-asides never envisioned by the architects of the civil-rights revolution. Preferences, quotas, and set-asides of various kinds have accentuated divisions in American life when the original goal of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts was to overcome them. The Court’s decision two years ago to ban racial preferences in college admissions, combined with the Trump administration’s assault on discrimination, quotas, and “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI),” has pushed what remains of the DEI regime into a near-terminal decline. A similar decision by the Court in this case will leave proponents of DEI with few avenues left by which to advance their agenda.

This case is the latest sign that we are approaching the end of the “rights” revolution that began six decades ago. The “rights” movement has achieved nearly all of its worthwhile aims but now lacks purpose in a nation that is much changed racially and demographically since the 1960s.

The facts are not in dispute. Louisiana was apportioned six congressional seats following the 2020 census, the same number as the state received after the 2010 census. The legislature approved a post-census map with five white-majority districts and one black-majority district, similar to the map used during the previous decade and precleared by the Justice Department after the 2010 census. The legislature did not expect a challenge to its revised map.

Nevertheless, minority plaintiffs challenged the map in federal court, claiming that there are enough black voters in the state to justify a map with two black-majority districts—and, further, that such a map is required under Section 2 of the VRA. Blacks, they point out, make up 30 percent of the state’s population, and so are entitled to two rather than one of the six congressional seats. The plaintiffs submitted a map that subtracted some of the excess black voters from the state’s majority-black district and reallocated them to a new district with a majority of black voters. In their view, the state’s map diluted black votes by packing too many of them into one “safe” district. They pointed to a case from Alabama (Allen v. Milligan), decided just two years ago, in which the Supreme Court accepted this argument.

The district court, after hearing preliminary arguments, ruled that the plaintiffs were likely to prevail at trial, citing the Supreme Court’s decision in the Alabama case. The state of Louisiana, after failed appeals, conceded the point and proceeded to draw a new map with two black-majority districts. Legislators understood, as many said at the time, that they were required by the court to consider race as the major factor in drawing the new maps. They also understood that if they did not draw the map, then the judge would do it for them.

But rather than accepting the map suggested by the plaintiffs, the legislature drew its own map with the goal of protecting influential Republican representatives, notably Speaker of the House Mike Johnson and House Majority Leader Steve Scalise. This is why legislators did not want either the judge or the minority plaintiffs to draw the new map, as they feared those maps would cut these incumbents out of their districts.

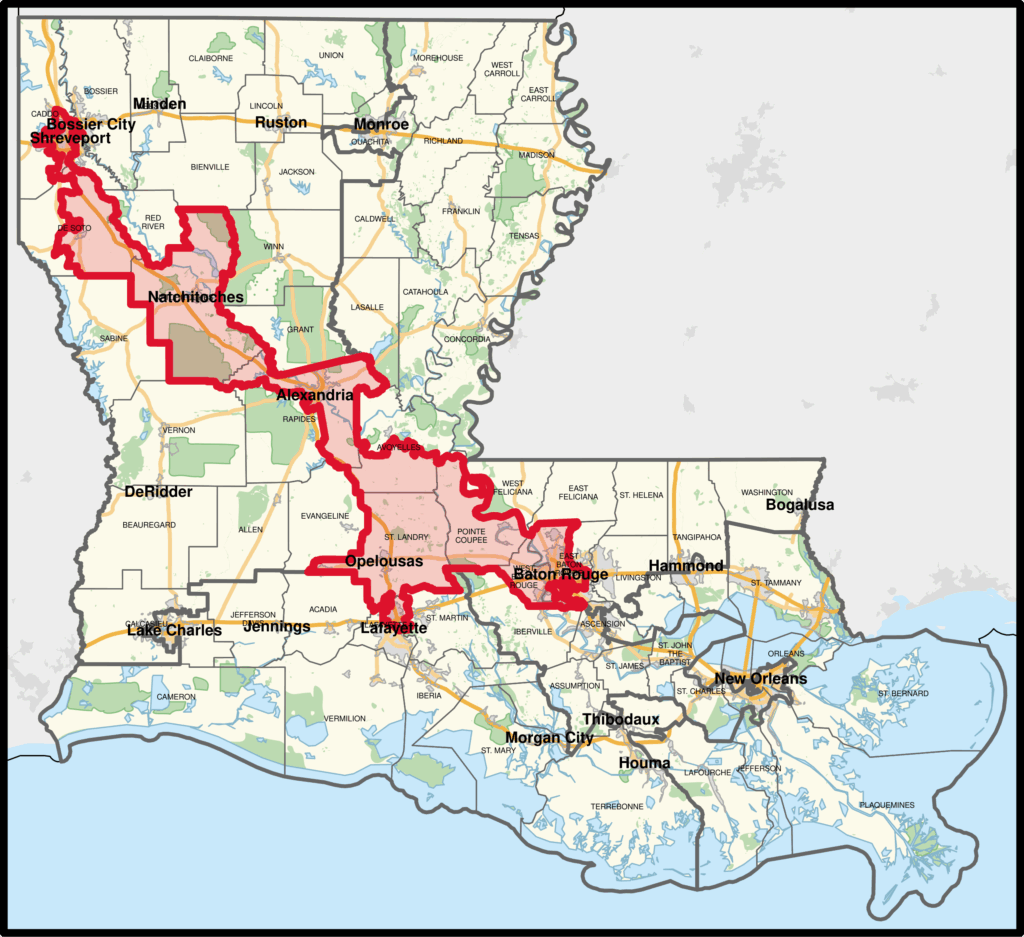

These calculations produced a second black-majority district (the Sixth District) in an elongated shape that runs from Baton Rouge in the southeastern part of the state to Shreveport in the northwest, covering a distance of 250 miles. The map looks a good deal like those that the Court has thrown out in the past as unlawful gerrymanders.

When the legislature approved this map, another set of voters, describing themselves as “non-African American,” filed suit in a different federal court, claiming that the map violates the Constitution because it was drawn with a racial result in view—a practice the Supreme Court has frowned upon in the past. After hearing arguments, a three-judge panel in the Western District of Lousiana struck down the state’s revised map as an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. The district court barred the state from using the maps in future elections, but the Supreme Court stayed that order pending a full hearing on the case. This decision is now under appeal at the Supreme Court.

This ruling made the state subject to two competing federal court orders, one requiring the new maps under the Voting Rights Act, the other prohibiting them under the Fourteenth Amendment. Several states submitted amicus briefs asking the Court to provide some clarity so they can proceed to draw legislative and congressional maps without concerns about protracted lawsuits. In view of existing precedents, the justices may be hard-pressed to satisfy them—which is why some are calling for a wholesale review of its jurisprudence under the VRA.

Congress passed the Voting Rights Act to protect minority voters by banning literacy tests, overly cumbersome registration requirements, and the like. The legislation worked: by 1980, black voter participation across the South matched white participation. That is still the case today.

But the Supreme Court soon expanded its reach to cover election rules and the drawing of districts. As Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in Allen v. State Board of Elections (1969), “the right to vote can be affected by a dilution of voting power, as well as by an absolute prohibition on casting a ballot.” This decision marked a shift in jurisprudence under the VRA, from protection of voting rights to a guarantee of electoral outcomes—or, as some have called it, affirmative action applied to elections. Subsequent court decisions, interpretations by the Justice Department, and congressional amendments have solidified the view that the VRA bans district maps that deny minority voters an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice.

As a result, the Supreme Court has wrestled for decades with redistricting issues. In Thornburg v. Gingles (1986), the court advanced a vague multistep test to demonstrate dilution of minority votes: a minority group must show that it is sufficiently large and compact to form a majority in a single-member district, and it must show that blacks and whites vote cohesively in opposite directions. These claims, if met, would entitle the group to one or more minority-majority districts. An unfortunate side effect of Gingles was to encourage bloc voting by minority voters, since this was now a condition for claiming additional minority-majority districts.

The court refined the tests in later cases, holding that states can’t use race as a predominant factor in drawing district lines and should not allocate districts to minority groups according to their proportions in the population, though plaintiffs continue to make this case under the VRA. The court has also struck down extreme racial gerrymanders—badly misshapen districts drawn only to guarantee black majorities.

Liberals were encouraged by the decision two years ago in Allen v. Milligan, a districting case from Alabama in which the Court ruled in a 5–4 decision in favor of minority plaintiffs and upheld the Gingles standards in VRA cases. They insist, in briefs and commentary, that the Alabama ruling provides a road map for the Court to follow in the Louisiana case.

But earlier this year the Court threw them a curveball by ordering a rehearing of the case in order to address a narrower question, to wit: “Whether the State’s intentional creation of a second majority-minority congressional district violates the Fourteenth or Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.”

In reframing the controversy, the Court elevated it from a statutory to a constitutional issue. The question is no longer whether the race-based district accords with the Voting Rights Act but whether this interpretation of the Voting Rights Act is constitutional in the first place. Democrats and civil-rights activists have taken this as a sign that the Court is likely to strike down race-based districting as a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

This points to a major difference between the Alabama and Louisiana cases, and a highly consequential one. The defendants in Louisiana make an equal-protection case under the Constitution, while in the Alabama case the state challenged the Gingles standards, allowing a majority of justices to uphold Gingles without reaching the constitutional issues. In Louisiana, the case hinges on constitutional interpretations.

Louisiana legislators openly admitted that they drew the revised district maps by using race as a major factor, which the state denied in the Alabama case. Those legislators proceeded to create a bizarrely shaped district to comply with the VRA, making it vulnerable to charges of racial gerrymandering. The disparate facts in Callais give the Court other possible paths to follow.

Despite the decision in the Alabama case, the Court failed to clarify the Ginglesstandards, and merely upheld them, albeit unconvincingly so. State legislators still find themselves in an uncertain situation: they may consider race to satisfy the VRA, but not too much lest they violate the Constitution; they may draw bizarrely shaped districts, but not excessively so lest they create racial gerrymanders. It is little wonder that legislatures are confused over what they are required to do under the VRA.

Chief Justice John Roberts, in his commentary on the Alabama case, acknowledged that “Gingles and its progeny have engendered considerable disagreement and uncertainty regarding the nature and contours of a vote dilution claim” under the VRA. Justice Kavanaugh, in a concurrence to the Alabama decision, wrote that “the authority to conduct race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future.”

Other justices seem ready to revisit the Gingles standards. Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justices Barrett, Gorsuch, and Alito, argued in a recent dissent that Section 2 of the VRA refers only to barriers to voting and doesn’t extend to redistricting or claims of vote dilution. As Thomas wrote, the words in the VRA reach only “enactments that regulate citizens’ access to the ballot or the processes for counting ballots” and do not include “a State’s . . . choice of one districting scheme over another.” That approach, if accepted by a majority, would foreclose most such litigation. It would also be consistent with the language of Section 2, which bans state-enforced race-based barriers to voting.

The court has also recognized that it is difficult to separate racial and partisan gerrymandering when blacks vote overwhelmingly for Democrats and whites heavily for Republicans. Justice Alito made this point in a dissent in a voting-rights case from North Carolina (Cooper v. Harris, 2017): “If 90 percent of African-American voters cast their ballots for the Democratic candidate, as they have in recent elections, a plan that packs Democratic voters will look very much like a plan that packs African-American voters.” In that circumstance, he asked, how is it possible to distinguish between a case of racial districting and one of partisan districting? The results in both will look the same. The Louisiana legislature, in drawing the initial map that was tossed out by the federal court, may have considered party much more than race, since partisanship operates as a proxy for race.

Viewed this way, the controversy looks less like a battle over minority voting rights and more like a typical partisan dustup over district lines. The VRA was intended as a shield to protect minority voting rights, but it has evolved into a sword to advance the interests of the established political parties.

Louisiana v. Callais gives the court an opportunity to revisit precedents that have provoked litigation over districting, inflamed racial conflict, and encouraged bloc voting under the VRA. In doing so, justices can restore the act to its original purpose of protecting minority voting rights. A new order may be on the horizon, one where the color-blind ideals of the civil-rights revolution are honored more in practice, and not just in rhetoric.