Gabriele Münter (1877–1962), who appears at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris down the hall from an exhibition celebrating Matisse and his enchanting daughter Marguerite, will be a revelation for those of us who need to brush up on our German Expressionism. It is the first retrospective about her to appear in France, and it belongs to a series of exhibitions the museum has presented about female artists with Parisian connections: Sonia Delaunay in 2014–15, Paula Modersohn-Becker in 2016, and Anna-Eva Bergman in 2023. Gabriele Münter was a co-founder of the group Der Blaue Reiter (meaning “The Blue Rider”) based in Munich, and she shared her life with Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) from 1902 when they met at the Phalanx School in Munich until World War I divided them. Nevertheless, though influenced by Kandinsky, she remained her own woman, and her art continued to develop after their separation.

In 1898, Münter and her older sister Emmy traveled to the United States, where they had family connections, and stayed there for two years. She bought a Kodak camera, a recent invention, and took hundreds of photographs. One of these, Three Women in Sunday Dress (1900), shows a trio of black ladies, garbed in majestic white gliding towards the camera on June 19, 1900, a day described in a caption as Juneteenth. Later, in Tunisia with Kandinsky in 1904–05, Münter produced more photographs, as well as paintings, drawings, and textiles. Tunisian architecture and local life enthralled her, not least for the bright colors.

She was encouraged as an artist by her affluent family. Both of her parents died when she was young, which provided her with an inheritance that gave her the ability to pay for private art lessons (German academies were then barred to women), through which she met Kandinsky, one of her teachers. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Paris was the center of the art world; most artists regarded a Paris stint as obligatory, and some made it their base. Münter and Kandinsky moved there in May 1906, living in the Latin Quarter and then in Sèvres. From November 1906 until March 1907, Münter rented a room at 58 rue Madame, where Sarah and Michael Stein, the sister-in-law and older brother of Gertrude and Leo, lived and welcomed guests to their Saturday evenings. Their connection with Gabriele Münter suggests a link to the neighboring Matisse exhibition down the hall, since the Steins were patrons of Matisse, and in the Stein home Münter would have seen paintings of his (as well as works by Gauguin, Bonnard, Cézanne, and Picasso) and perhaps even the artist himself. Her first Parisian sojourn encouraged her to brighten her colors and free her brushstrokes. Her 1906 linotype sketch on Japanese paper of her maid, Aurélie, with the maid’s animated, mischievous eyes rendered in strong strokes, here provides an example of the many prints she made in Paris.

Upon her return to Germany, Münter threw herself into the vital art scene in Munich. With her inheritance, she bought a house in Murnau, a village an hour by train from Munich distinguished by its colored houses, right on the Staffelsee and surrounded by marshes and mountains. She was a founder of the New Artists Association and, in 1911, Der Blaue Reiter, whose other founding members included Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke, and Paul Klee. In Murnau, she worked with artists who shared her love of nature and landscape, often approached in folk-art fashion as if through a child’s eyes. Landscape with a Cabin under a Setting Sun (1908) features flamboyant colors: a blue mountain, red poppies, shades of green grass. Portrait of Marianne von Werefkin (1909) is no less brightly colored, with a mauve scarf over a white coat against a yellow background and a face emanating gaiety. Marianne von Werefkin (1860–1938), born Mariana Vladimirovna Verevkina to a Russian noble family, was drawn to the freedom she discovered in Munich at the time. She trained in Russian Realism but joined the Expressionists. She and another Russian noble and painter, Alexej von Jawlensky (1844–1941), shared a house in Murnau with Münter and Kandinsky. Münter’s portrait of Jawlensky, Listening (1909), is endearing. His face is as pink as his shirt. The expression on his egg-shaped face is comical and at odds with the fierceness in his own self-portrait from four years earlier. Münter’s self-portrait of about the same period (ca. 1909–10) shows a harrowed, frowning face in pale colors, in contrast to her usual bright shades.

Resident of Murnau (Rosalie Leiss) (1909) has a background that reminds me of Rembrandt, who might have been pleased to paint this elderly lady eagerly clutching her stick. Mme. Olga von Hartmann (ca. 1910) shows the singer with a pinched face in red and gray against a green background.

A few years after this burst of creativity at the end of the century’s first decade, Münter and her Russian housemates ran into World War I. The four decamped to Switzerland in 1914, but Kandinsky, considered an enemy alien, was forced to return to Russia later that year. The Jawlensky–Werefkin pair stayed in Switzerland, which turned out to be the better fate for well-born Russians once their world exploded in 1917. Münter herself spent the war in neutral Scandinavia, where she was acclaimed as an important figure. Hearing no news of Kandinsky, Münter tracked him down through the Red Cross. She discovered that he was now married and a father.

When she returned to Germany in 1920, she felt she needed to pursue a new path. She was fascinated by the “new women” of the period she met in Berlin and in Paris, where she spent another sojourn in 1929–30. Her work, for years in the doldrums, really picked up after she made a new companion in the art historian and philosopher Johannes Eichner in 1927, proving that female artists need muses no less than men do. Short of studio space during the late 1920s, she turned to her original preference of drawing. In a few lines, she could conjure a face, an expression, or a gesture. Her sketch Poet E. K. (Eleanora Kalkowsky) (ca. 1926–27) is an example.

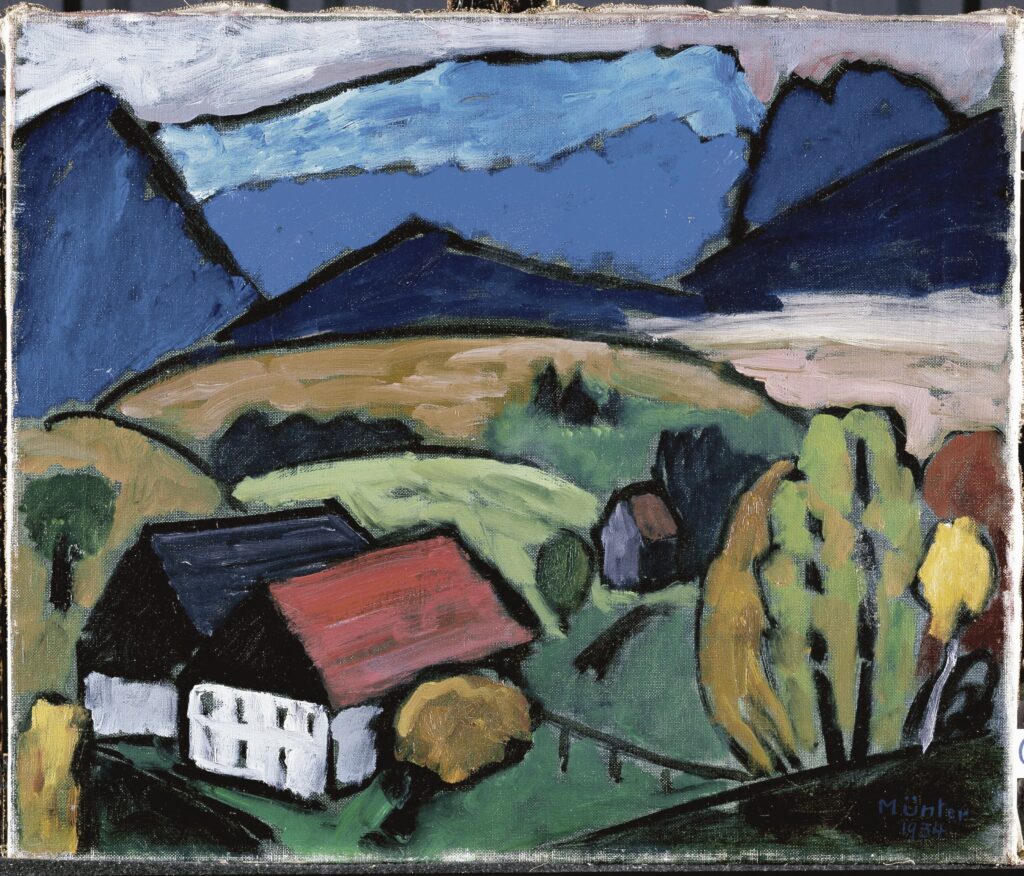

In 1931, she and Eichner installed themselves permanently in her house at Murnau. View Over the Mountains (1934) shows a quieter, more peaceful vision, in contrast to events in Germany. Münter tried to fit into the new regime, joining the Reich’s Fine Arts Chamber and producing two tableaux, not included in the exhibition, of Adolf Hitler’s Routes in Art in 1936. Her attempts at appeasement failed, however, and her work was put on the list of degenerate art. She was forced to lie low, hiding her and other Blaue Reiter work in her basement. After the war’s end, she and her work were rediscovered. This attractive exhibition gives a chance for Parisian art-lovers to appreciate an artist little known outside of her native land.