Henri Matisse (1869–1954) is one of France’s most famous artists, but his only daughter, Marguerite (1894–1982), is almost unknown, despite her being her father’s most frequent model and, at times, his adviser and even agent. A moving and appealing exhibition at Paris’s Musée d’art moderne concentrates on the influence she had on her father and shows examples of her little-known work as a painter and a fashion designer, as well as her heroism in the Second World War.

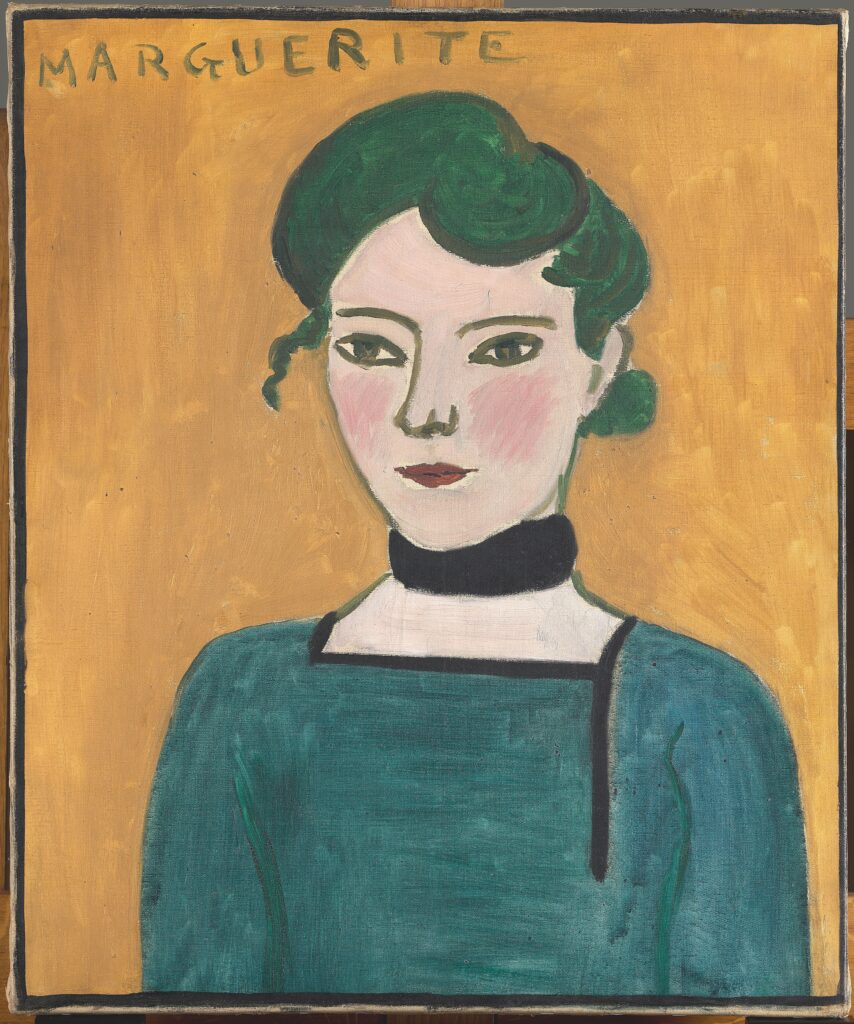

Marguerite was the result of a brief fling between Matisse, then studying painting, and his model Caroline Joblaud. Two and a half years later, in 1897, Matisse legally recognized her as his daughter, and Amélie Parayre, who married Matisse in 1898, raised her as a daughter. The family, which soon included two sons, Pierre and Jean, called her “Margot.” When she was seven, a case of diphtheria marred what might have been a blissful childhood. The resulting tracheotomy left her with a scar on her neck, which she hid by either high collars or a black ribbon tied like a scarf. Matisse was earning a living for his family with his artwork, helped in large part by American patrons like the Steins and the Cone sisters of Baltimore. In Girl Reading (1905–06), paintedat the Quai Saint-Michel where the family lived when in Paris, Matisse depicted Marguerite reading, her hand supporting her head, in rapid brushwork and bright Fauve colors. In Marguerite Reading (1906), donein the house the Matisses rented in 1906–07 in the fishing village Collioure, we see her in a more sober, meditative setting, the blue-white background indicating the sea’s intimacy. An ink drawing, Marguerite (ca. 1906–07), shows the playful little girl her father adored. A painted Marguerite, also from 1906–07, shows the sweet girl developing into adolescence with a fiery, intense gaze, her black ribbon bold against a simple monochrome mustard background. In a painting from three years later, while the family was living in Issy-les-Moulineaux, Marguerite sits, her white face dotted with pink blush, with a cat as black as her hair perched on her lap. Matisse lent this painting to the 1912 Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition in London and the New York’s 1913 Armory Show, but he kept it for himself to the end of his life. It was not the only picture of Marguerite that Matisse held on to. Marguerite chided him for that, reminding her father of the importance of having his work hanging in museums rather than in his rooms; she would always be there for him to paint. As it turned out, she was far less available as a model once she married the writer and art critic Georges Duthuit in 1923. Matisse’s pencil drawing of his son-in-law is in the exhibition, with a caption noting that Duthuit admired his father-in-law but feared that Matisse disliked him. The married Marguerite never posed for her father again, other than during an emotional reunion at the end of World War II.

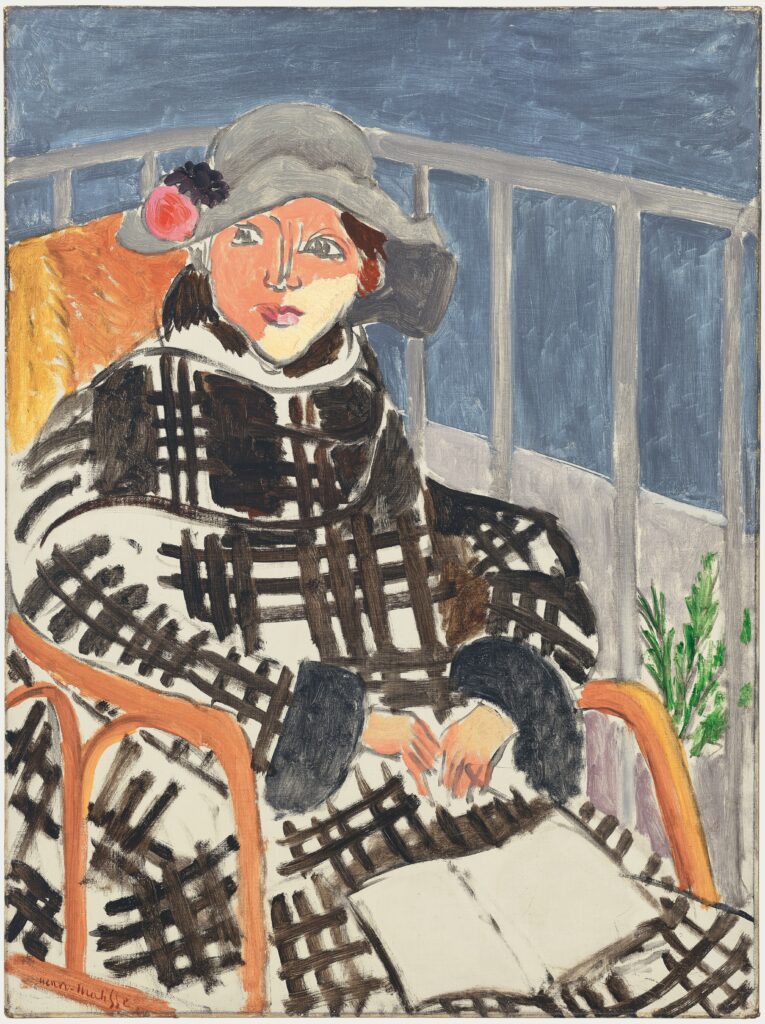

Marguerite’s ill-health in childhood made her a “studio kid,” often sitting for her father and witnessing his “daily drama,” as she put it, as an ever-striving artist. She and her brother Pierre, who grew up to become a leading New York gallery owner, left home in 1912 to study at their aunt Berthe’s teachers’ college in Ajaccio, Corsica. After two years, she abandoned her hope of earning a degree and returned home. Her father took advantage of her presence to use her as a model as he experimented in new forms. From today’s vantage point, Matisse seems less a daring pioneer than a continuing practitioner of the French tradition, going back to Simon Vouet, of celebrating the sweet life. In Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, Anthony Blanche dismisses English art as “simple, creamy English charm, playing tigers.” The same can be said for much of French art. In White and Pink Head (1914–15), Marguerite modeled for Matisse’s version of Cubism, sweeter than anything Picasso or Braque produced, even if the bars and stripes make her look as if she’s in a cell. In early 1918, while war raged in France, Matisse began to spend more time in Nice. Miss Matisse in a Scottish Plaid (1918) showed “Margot” sitting on a balcony over the blue sea, bundled up against the cold. She seems more of a bright poppet than she did a few years before. Back at Issy-les-Moulineaux in the summer of 1919, she is very much a young woman, posing with a family friend in The Tea.

In that picture, she still had the black ribbon around her neck, but she was freed from it after an operation in spring 1920. Matisse took her to Étretat, near the Channel, so she could convalesce, while he discovered a new region. Marguerite Sleeping (1920) shows her in slumber, her hair spread on a pillow. She accompanied her father when he returned to Nice in the autumn of 1920. In the South, Matisse posed Marguerite with a professional model, Henriette Darricarrère, whose fairish hair contrasts with Marguerite’s darkness. The Moorish Screen (1920)shows the pretty young women in light summer dresses in a room, its floors draped with Turkish rugs and Matisse’s open, empty violin case on a bed. After Marguerite’s marriage, which produced a son, Marguerite became her father’s agent rather than his model. Her opinions were forthright. “I think daddy wore out the light in Nice,” she wrote. “I don’t mean to say that I don’t like these canvases . . . but I think that a certain kind of profound emotion is achieved more readily if it isn’t drowning in light.”

Marguerite was herself a promising painter. The Cone sisters of Baltimore bought a few of her works, including a ravishing picture of Nice’s seascape (ca. 1926) and some self-portraits, on loan from the Baltimore Museum of Art for this exhibition. For a time, she also hoped to make her name as a clothing designer, and in 1935 she presented a collection of around twenty styles in England. Her work was well received, but she gave up dress-designing just as she did painting. The exhibition’s captions suggest that she may have lacked confidence.

Be that as it may, Marguerite, who had once been a sickly child, proved herself a heroine in the French Resistance—as did her stepmother, though the exhibition doesn’t mention the latter. Peter Quennell wrote in his 1980 memoir, The Wanton Chase, that Matisse, exasperated on hearing that his womenfolk had been captured and were in danger of being tortured and deported, complained, “Those two women would do anything to stop me working!” The exhibition claims instead that Matisse, in Vence, was ignorant of what was going on. Marguerite was captured, tortured, and imprisoned in Rennes, where she was set to be deported to Germany. Just in time, the Allies liberated Rennes, and she was set free in Belfort, already on her way toward the German border. Father and daughter met again in January 1945 in Vence. Matisse was horrified by Marguerite’s experiences, and he made beautiful charcoal sketches of her, the first he had made in two decades and the last he ever did. The sketches, alongside exquisite music by Satie, provide a fitting conclusion to a beautiful exhibition, one that makes the visitor appreciate Matisse all the more as well as introduces his delightful daughter.