In 2018, when the company’s market capitalization was about $45 billion, Tesla shareholders approved a new compensation package for Elon Musk. By any measure, the package was extraordinary. It came in 12 tranches, each equal to 1 percent of the company’s outstanding common stock. To receive his payments, Musk had to boost Tesla’s market cap by $50 billion for each installment—more than the market capitalization of General Motors at the time. Thus, to earn all 12 tranches, Musk, who already owned about 22 percent of the company’s shares, needed to grow Tesla’s value from $45 billion to $645 billion. If he did that, he would receive stock in the company worth about $56 billion—the largest potential compensation package in American history, but less than 10 percent of the potential $600 billion gain to shareholders.

The market was shocked. Almost no one, other than Musk, thought the goals were realistically attainable. But holders of 76 percent of the Tesla shares approved the package. To almost everyone’s surprise, other than Musk’s, he delivered. The company’s value increased more than $600 billion, and the richest man in the world collected $56 billion of Telsa stock. Today, the company is worth more than $1 trillion.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

But in 2024, the Delaware Court of Chancery found that the compensation package was unfair to Tesla and its shareholders and forced Musk to return the stock. Tesla then sent a copy of the court’s opinion to every shareholder, called another meeting, and asked the shareholders to ratify the package—that is, approve it again, retrospectively. This time, 77 percent of the shares voting approved. Further signaling their displeasure with the court, shareholders approved reincorporating the company in Texas. The Court of Chancery then determined that the ratification vote was ineffective. Both decisions are now on appeal to the Delaware Supreme Court.

If you have heard about companies considering leaving Delaware for Texas or Nevada, this case, Tornetta v. Musk, is the reason why. The Court of Chancery made a serious mistake that affected more than just Tesla and Elon Musk. With most public companies incorporated in Delaware, the Delaware courts, globally renowned for their objectivity and commercial sophistication, supply corporate law to the nation. They are an important national asset. To maintain their integrity, the state’s supreme court should overrule the Court of Chancery’s decision.

To understand what went wrong in the Musk case, consider some relevant background.

The basic theory of corporate law is that directors, acting within the law, have a fiduciary duty to manage a corporation for the benefit of its shareholders. Because managing a business is extremely complex and business decisions are inherently risky, when a shareholder challenges a business decision made by directors, courts apply the so-called business judgment rule. Under that rule, courts will not interfere or second-guess a decision unless it has no “rational business purpose”—that is, it is so irrational that no person of ordinary sound business judgment could think that the exchange was fair to the corporation. This is a very high standard, and it applies only in extreme cases; to my knowledge, no public-company directors have ever been found to have violated it.

Courts apply a different standard, however, if directors have a conflict of interest—for example, if the directors are selling to the company a parcel of real estate that they themselves own. In these cases, the court will review the transaction to make sure it is “entirely fair” to the corporation and its shareholders. The “entire fairness” standard requires directors to prove that both the process whereby the transaction was negotiated and approved and the substantive economic terms of the transaction (e.g., the price) were fair to the corporation and its shareholders.

When a shareholder challenges in court a business decision that the directors made, the most important question is often which standard of review—the “business judgment” standard or the “entire fairness” standard—the court will apply. If the court reviews the decision under the business-judgment standard, the directors are almost certain to win. If the court reviews the decision under entire fairness, however, the directors face longer odds.

But corporate law encourages directors to avoid entire fairness reviews by adopting procedures to neutralize conflicted decision-makers by assigning the decision to unconflicted individuals—for example, by forming an “independent committee” of unconflicted directors who negotiate for the corporation and ultimately decide whether to approve a transaction in which other directors are interested. In those cases, the courts review the independent committee’s decision under the business-judgment standard.

Sometimes, to find an unconflicted decisionmaker, the corporation must push the transaction to shareholders. This is the usual procedure by which corporations decide directors’ compensation, given the obvious conflicts involved. Directors propose their own compensation package to the shareholders, who then vote on it. If shareholders approve, the courts will review the package under the business-judgment standard, and it will stand.

Things are different, however, if a single shareholder owns a majority of the voting power within a corporation (a “controlling shareholder”). Such a shareholder can determine who will be elected as directors and so effectively controls the board. In this case, the law holds the controller to the same standard as directors, imposing on him fiduciary duties for the benefit of the minority shareholders. As a result, courts review any transaction between the controller and the controlled corporation for entire fairness.

A shareholder who owns an absolute majority of the voting shares is a controller. But Delaware law has always recognized the possibility that a shareholder with less than an absolute majority of the votes may be a controller if, in addition to owning a substantial proportion of shares, other factors show that he effectively controls the board. For example, in Kahn v. Lynch (1995), the Delaware Supreme Court found that a shareholder who owned about 43 percent of the company’s shares, had a right to appoint five of the 11 directors, and had additional contractual rights to block certain transactions was, in fact, in control of the company. Accordingly, it reviewed a merger between the company and the controller for entire fairness.

While the result in Kahn v. Lynch is surely right, Delaware courts in recent decades have slowly expanded the notion of a controlling shareholder, lowering the number of shares that a shareholder needs to hold and relying on softer factors to find control.

The Court of Chancery, without any support from the Delaware Supreme Court, has gone further, creating the so-called transaction-specific controller doctrine. Under this framework, a shareholder, while not a controller in either sense—he has neither an absolute majority of the shares nor the actual power to control the board—may exercise so much influence over a particular decision by the board that the court treats him as if he were a controlling shareholder for purposes of the relevant transaction. This means that the court will review the transaction for entire fairness.

This new doctrine is incoherent. The reason a court asks whether a shareholder is a controller is to determine which standard of review to use in assessing a transaction between the shareholder and the corporation. The court cannot review a challenged transaction until it first determines which standard of review to use.

The transaction-specific controller doctrine inverts this logic. The court first looks at the process by which the challenged transaction was approved, applying no defined standard of review. If the court finds that, even though a transaction was nominally approved by an independent committee, the shareholder was too involved in the decision-making process, then the court will conclude that the shareholder, regardless of how many shares he holds, was a transaction-specific controller. The court then subjects the transaction to an entire-fairness review. Since entire fairness includes the fairness of the procedure by which the transaction was approved, the very facts that led the court to conclude that the shareholder was a transaction-specific controller will also usually lead the court to conclude that the process by which the transaction was approved was unfair. Absent the most extraordinary showing about the fairness of the price, the result will be that the transaction was not entirely fair to the corporation.

This is essentially what happened in Musk’s case. He owned about 22 percent of the Tesla shares—nowhere near an absolute majority. And unlike the controlling shareholder in Kahn v. Lynch, he had no right to appoint directors or contractual rights to veto corporate transactions. The only other power Musk had over Tesla was his immense talent as a chief executive officer. He could hurt Tesla, in other words, by quitting, or just by not working as hard as he usually does. But Telsa does not own Elon Musk; if the company wanted Musk to stay on, it had to pay him enough to make it worth his while.

The court found that Musk took the lead in arranging a new compensation package once his old one expired. He proposed the key terms of the deal, and the other directors went along with whatever he suggested. At one point, Musk, on his own initiative, even reduced his request because he thought it was too much.

This analysis led the court to conclude that Musk was a transaction-specific controlling shareholder. Yet this conclusion, for all the court says, would have followed even if Musk had owned but a single share of Tesla stock, or even no stock.

Once Musk was found to be a controller, however, the court had to review the package for entire fairness, and the same facts that led the court to conclude that Musk was a transaction-specific controlling shareholder then led it to conclude that the process whereby the transaction was negotiated and approved was not fair.

The court also looked to the compensation packages of other superstar CEOs with significant equity holdings at similar companies—Jeff Bezos at Amazon and Mark Zuckerberg at Meta—and noted that those executives get paid nothing. Like Musk, each owns a substantial minority of the share of the company, and in both cases the directors of the company have concluded that such ownership gives the executive a sufficient incentive to work hard to increase the company’s share price. The court did not quite say it, but its clear implication is that a fair price for Tesla’s deal with Musk should have been zero.

But this overlooks the obvious difference between Musk, on the one hand, and Bezos and Zuckerberg, on the other. Unlike those superstar CEOs, Musk also has significant stakes in and is also CEO at several other highly successful companies, such as SpaceX. Bezos’s best opportunity to increase his wealth is by running Amazon; the same is true for Zuckerberg at Meta. Musk, however, has multiple such opportunities. If Tesla wanted to get a lock on Musk’s time, it had to offer him more than he could hope to get at his other companies. Tesla’s board did the rational thing, and it worked.

Realizing that this outcome threatens to undermine Delaware’s business-friendly reputation, the state’s general assembly intervened earlier this year and amended the Delaware General Corporation Law to provide that, in most cases, courts cannot deem a person with less than a third of a corporation’s voting power to be a controlling shareholder. The law does not apply retrospectively, though, so it will not affect Musk’s appeal in the Delaware Supreme Court.

This change, while beneficial at the margins, evades the real problem: the transaction-specific controller doctrine. The doctrine is incoherent, and it never had any basis in the decisions of the Delaware Supreme Court. The court should abolish it.

If he prevails on appeal, Musk intends to use his $56 billion from Tesla to fund his plans at SpaceX to colonize Mars. I don’t care about Mars, but I do care about Delaware. Musk deserves his $56 billion, and if the Delaware Supreme Court agrees, it will restore the integrity of the state’s long-hallowed courts.

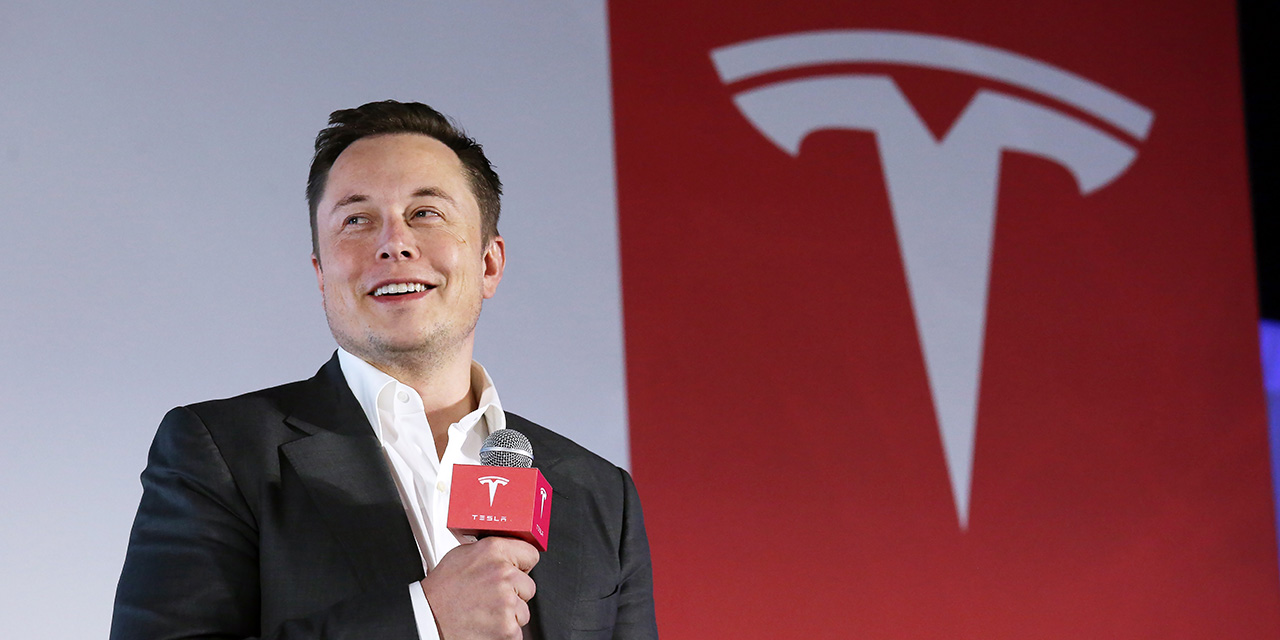

Photo by Nora Tam/South China Morning Post via Getty Images

Source link