The Museo M9, billed as the “Museum of the 20th Century,” lies amid the modern urbs Venice Mestre, dominated by industrial buildings, docks, and a sea of hotels, the last of these offering more-affordable accommodation to tourists spending time in premium-priced Venice. It is unlikely that a reincarnated Ruskin would stay here. The ultra-modernist M9 building is a striking construct: completed in late 2018, it would serve well as a sinister headquarters in a dystopian science-fiction movie.

Foreboding as the museum is, its third-floor space for temporary exhibitions is superb. An open room of some 15,000 square feet, cleverly and subtly divided by display walls that guide an effortless flow through each show, it has fantastic lighting and indulgently generous space. In all, it generates the perfect atmosphere for art lovers.

Its big exhibition this year is “Arte Salvata: Masterpieces Beyond the War from the MuMa in Le Havre” (I provide the museum’s own official translation, which comes across as a bit clunky).1 This is an intimate collaboration with Le Havre’s Musée d’art moderne André Malraux (“MuMa” for short), which has never previously lent from its collection. That museum boasts an important gallery of Impressionist art, as befits the place where Monet grew up and created his first works. But as this exhibition so ably shows, MuMa’s collection extends well beyond that era: while there are a good few Monets in “Arte Salvata,” there are considerably more Dufys. Le Havre, like Mestre, was bombed heavily in World War II, pretty much razed to the ground; the collection on display represents a celebration of the art saved from that destruction, eighty years after the end of the war.

And quite a celebration it is. Over fifty works by Renoir, Monet, Braque, Dufy, Boudin, Sisley, Bonnard, and Gauguin hang alongside less-famous artists who have no need to feel embarrassment in juxtaposition: Jean-Francis Auburtin (with no fewer than four pieces); Lucien Hector Monod; René Ménard; Charles Victor Guilloux; Maxime Maufra, in four striking works including the splendid nighttime village scene Moonrise in Brittany (1899); Émile Othon Friesz; and on it goes. The consistent quality of the works on display is a distinguishing feature of this show.

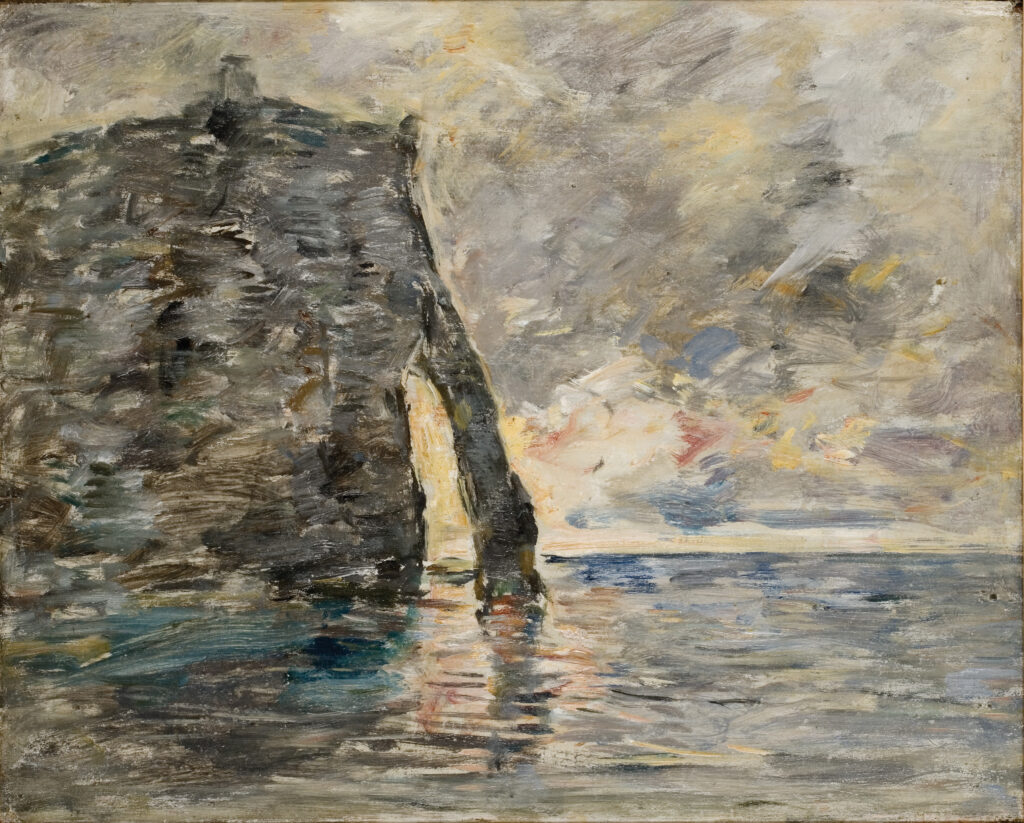

Although the poster for the exhibition features Renoir’s The Hiker (1895), seascapes and harbor scenes dominate. Their sense of airiness and expansiveness are boosted by the concomitant capaciousness of the exhibition room. Boudin’s study of Clouds in a Blue Sky (1888) initiates proceedings with a light touch, while Maufra’s Ocean Liner Leaving Port (1905) captures a busy harbor scene of sail and steam. Shortly after follows Monet’s Cliffs of Varengeville (1897). A theme of dynamic color is quickly established—and also, in the early part of the show, a theme of cliffs, with Varengeville alone featured four times. The obligatory Sisley (I have had cause before to state that seemingly no exhibition displaying art from this period can be without a Sisley) is The Seine at Pont-Jour (1877), one of his more accomplished works—classically impressionistic, with a thin strip of land and buildings dividing the mixing whites and blues of river and sky. Two late Boudins, The Cliffs of Étretat (ca. 1890–91) and The Point of the Razor (another coastline scene, from 1897, the penultimate year of his life), capture the familiar scene repeatedly painted by Monet and other Impressionists, thereby underscoring MuMa’s connection with the Normandy coastline. As enjoyable as these paintings are, and as important as Boudin was in being a forerunner of the Impressionists, they do not quite rival the achievements of his young friend Monet and the upcoming generation of artists.

There are plenty more coastline depictions from this earlier, chronological part of the show. Notable among these are Maufra’s Cliffs at Tranto (ca. 1895), in calming, twilight colors, and Henry Moret’s Lampaul Bay (1901), using heavy roseate and turquoise layers to capture the sea off Brittany. Monet’s ever-lovely, melancholic Winter Sun, Lavacourt (1879–80) provides one of the relatively few landscapes.

As the show moves firmly into the twentieth century, Albert Marquet and, even more so, Raoul Dufy dominate, the latter with some ten paintings on view, allowing an appreciation of his artistic development from his early, more conventional, and rather fine Port of Le Havre (ca. 1900) up to 1926 with another Port and Beach of Le Havre, which feels rather inconsequential. The port itself has a section dedicated to it, its best representation arguably being Marquet’s charming Dock of Le Havre (1906), in which Post-Impressionism meets Fauvism. Highlights from the later portion of the show include two works by Friesz: House Near La Ciotat (1907), in which the artist seems to be joyously messing up a Renoir landscape, and the wonderfully atmospheric Evening at the Old Dock of Le Havre (1903), with lights from harborside buildings and the moon reflected in the dark waters, after the day’s work has been completed—it is superb.

But we are still spoiled for choice; as I say, such is the consistency that there is no time for troughs to develop. Thus, we still have remaining Georges d’Espagnat’s Olive Trees in Brittany, Effects of the Sun (ca. 1900), the trees partially obscuring a bucolic house. And—oh, joy—Bonnard’s Interior with Balcony (1919), which is utterly typical and none the worse for that, its colorful lightness capturing much of the exhibition’s essence.

Apart from the rather incongruous contributions from the edges of the chronological parameters at either end (1866 and 1933), any apparent eclecticism is modulated by themes and by time, with the temporal boundaries being cleverly extended enough to follow significant developments in art over this period. One completes the viewing with a sense of having been on a wonderful, scenic journey.

Curated by Marianne Mathieu and Geraldine Lefebvre, the show is an unqualified success.

-

“Arte Salvata: Masterpieces Beyond the War from the MuMa in LeHavre” opened at the Museo M9, Venice Mestre, on March 15 and remains on view through August 31. ↩