Note: If joining “Saintly Influencers” for the first time today, please read the footnote, explaining its context, purpose, and aim.

The Renaissance and Baroque Age of Church history (roughly 1400 to 1660) was marked by a growing—yet sundered and suffering—European population, an expanded awareness and knowledge of geography, and new technological developments with potential to exert a deep impact on European culture. In some cases, these new trends marked the full flowering of the culture of the Middle Ages; in other cases, they incited revolution. The Body of Christ responded, and many holy men and women left their influential marks on the life of the Church for posterity’s benefit. Still, a handful of influencers exercised an influence that has outpaced or outlasted others’ over the last five centuries.

The first saintly influencer of this age is Blessed John of Fiesole (1386-1455). Born in Tuscany, John studied art as a young man in Florence, the city at the very epicenter of the artistic and literary Renaissance that swept across Europe through the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. During his studies, he was called to religious life, and so he entered the Convent of St. Dominic at Fiesole, just outside Florence. As a Dominican friar, he continued his work as an artist, and he produced paintings so beautiful that his confreres dubbed him the Angelic Friar, in Italian, “Fra Angelico.”

Fra Angelico produced an incredibly large body of work. Among his most identifiable paintings are Adoration of the Magi (with Filippo Lippi, which can be viewed at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.), Communion of the Apostles, Last Judgment, and (a personal favorite) Conversion of Saint Augustine. Of course, his Annunciation is among a handful of the most readily identifiable paintings in the history of western art. Art museums around the world seek out opportunities to add his works—those that are not frescos residing in Italian convents—to their collections. To view a broader range of the artist’s work in the U.S., one might visit St. Mark’s Catholic Church in Peoria, Illinois, containing the Shrine of Blessed Fra Angelico, in which nine reproductions of the friar’s paintings beautify the parish church for its sacred liturgies. Down to our own era of history, Fra Angelico serves as a saintly icon into the vast array of artistic beauty produced during the Renaissance.

Nearly a century later, the next influencer was born just before Europeans reached the New World. Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (1474-1548) was a native Aztec who heard the Gospel from Franciscan missionaries and was baptized in 1524. A few years later, he received an apparition from Our Lady at Tepeyac Hill, near Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital (generally, what is now Mexico City). His task from the beautiful woman, who appeared as a native Aztec, was to ask the bishop for a church to be built on that hill. The miraculous array of roses that were native to the bishop’s home region in Spain—proof of the heavenly provenance of the request—is a beloved saintly tale. From that miraculous moment, the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe was constructed.

Juan Diego’s influence was so great because his conversion, and especially his fiat to the Lord and the Blessed Mother, has transformed the Church in the Americas over the last five centuries. His faithful presentation of the message from Our Lady, led to the evangelization and conversion of millions of indigenous persons. Because of those conversions, Central America assimilated and lived by a Catholic culture. Now, several centuries later, the Catholic culture in the United States has been significantly transformed because of the need to operate by, and celebrate, this culture, too.

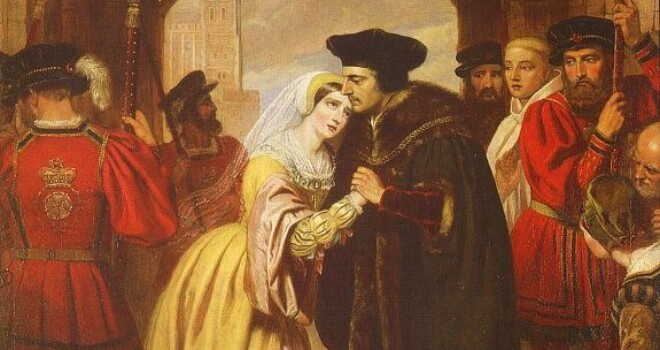

Also in the late-fifteenth century, back across the Atlantic, Thomas More (1478-1535) was born into a relatively wealthy English family. He attended a parochial school and, by the age of twelve, was a household page for the Archbishop of Canterbury. By age fourteen, he matriculated at Oxford University; by age sixteen, he left Oxford to train as a lawyer in London. From there, his noteworthy career in public service developed rapidly: in 1504, by age twenty-six, he won his first election to Parliament. In 1529, after an already illustrious career in public service, he won the favor of King Henry VIII and was made Lord Chancellor of England.

It was this relationship with King Henry which led to Thomas More’s greatest exercise of influence on the Church and western history. The king had given More the post with the unspoken expectation that the monarch would be able to control the Church because of More’s fealty. Rather than capitulate to Henry’s pride and greed, Thomas stood courageously against the usurping of legitimate authority, specifically on the principles of religious freedom. He was martyred in 1535, after he refused to surrender to King Henry’s power grab. At his execution, his final words were, “I die the King’s good servant, but God’s first.”

St. Thomas More’s witness has been especially poignant for western Christians in recent years, especially as we navigate life in an anti-Christian culture. His example causes us to expect that tyrannical kings, executives, legislatures, or judiciaries will not impinge on our freedoms of conscience and religion. Indeed, St. Thomas More’s influence—his witness and his intercession—has been robust and valuable in recent years in the United States as there have been multiple legal situations that have tested citizens’ conscience rights viz-a-viz the federal government.

A few years after St. Thomas More’s execution, Charles Borromeo (1538-1584) was born to a noble Milanese family. His father was a count and his mother was part of the wealthy Medici family. Despite this, by age twelve, he committed himself to a life of ecclesiastical service and, as a teenager, undertook studies in civil and canon law. When he was twenty-one, his uncle was elected pope, after which Charles was quickly named a cardinal-deacon and brought into the Vatican’s diplomatic service. The very next year, he was named administrator of the Archdiocese of Milan. At that point, Charles chose priestly ordination as the path for the remainder of his life. Within four short years, he received each level of Holy Orders. He was consecrated as the Archbishop of Milan at just twenty-six years old, near the end of the Council of Trent.

Charles Borromeo’s influence developed because of his dedication to the reform of the Church, both locally and universally, despite his young age. Before his ordination, he was influential in ensuring the continuation of the Council, committing to copying the proceedings by his own hand. Thus, in no small part, he ensured that posterity would have access to the canons and decrees of that important council. During its sessions, he was also intimately involved in developing the Roman Catechism, which provided the Church with her first systematic teaching manual. It was a catechism specifically meant to assist the formation of clergy in seminaries, aiding them in preaching and catechetical formation of the laity.

After the council, as archbishop, Borromeo emphasized reform of Church structures and the need for all Catholics to be formed in their faith. He helped found the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine (CCD), whose mission extended through Europe and later into the newly-founded United States. Clergy and laity associated with the confraternity worked to provide religious education to those who did not have access to formal schooling, primarily to children. To this very day, the formation of children and youth happens because myriad volunteer catechists steward their time and efforts to ensure that the Deposit of Faith gets handed on to the next generation.

The final influencer of this period was a pious and diligent young man born in the southwest of France. Vincent de Paul (1581-1660) entered seminary at 15 and was ordained at just 19 years old. A few years later, while he was sailing in the Mediterranean Sea, Vincent was captured and enslaved in northern Africa. After two years he managed to escape and return to France. A few years later, he went to Rome to continue his studies, and it was there his charism came to fruition: evangelizing and serving the poor in Europe’s biggest cities. Back in France, he began a mission as chaplain to the galleys, where he ministered to sailors and those who worked on the docks. Frequently, those laborers were convicted criminals. Thus, Vincent’s ministry was a combination of military chaplain and prison ministry.

The need for evangelization and works of mercy among the poor and the criminals was so great that Vincent de Paul founded a community of priests and an order of sisters, the Congregation for the Missions and the Daughters of Charity. Both religious communities have exercised significant influence throughout the western world for nearly four centuries. Two centuries after his death, one of the most recognizable lay apostolates in the world was named in honor of him: the Society of St. Vincent de Paul. In fact, if one types “St. Vincent de Paul” into a search engine, there will be dozens of links to local chapters of the society before even a biographical site is listed. This influence is extended not only by chapters of the Society, but also by the charitable, merciful works of organizations like Catholic Charities (in any country or in any particular diocese). They all take St. Vincent de Paul as their patron.

To be sure, these are not the only saintly influencers from this age of Church history. However, the names—and the images and words associated with them—are among the most easily-recognizable by casual Christians and even non-religious citizens of the west. For that reason, we implore their intercessors, and we seek to imitate their examples in the hope that the truth and love of Jesus will transform all.

[1] Learning about the lives of holy men and women is a common and helpful spiritual practice. But while we might take some time to consider saints in their historical contexts, it’s easy to look past the ways their lives and actions influence our own present culture. Saints are made within specific cultural, historical circumstances and, just as importantly, they have borne deep impact on this current age of history.

Thus, this series seeks to identify the saints from the history of our Church who have borne the greatest influence on our present culture, that is, the way we think about and experience the Christian life in our current era, and in our segment of geography (i.e., the West and, in particular, the United States). This series delineates Christian history into eight ages: the Apostolic Age (A.D. 35-100); the Early Patristic Age (A.D. 100-480); the Later Patristic Age (A.D. 480-800); the Age of Early Christendom (A.D. 800-1200); the Age of Later Christendom (A.D. 1200-1400); the Renaissance and Baroque Age (A.D. 1400-1660); the Modern Age (A.D. 1660-1900); and the Post-Modern Age (the twentieth century). Each essay within this series will examine a handful of saints who sought and found holiness within their historical epochs and who, in turn, have borne an outsized influence on the ways Catholic-Christians in the third millennium understand and live the Catholic Faith. These few in each essay are chosen from among many, many other saints whose influence could be included in this series as well.

The great hope is that learning these influences gives us inspiration and stamina as we seek to answer the call to holiness in the world and the culture of the twenty-first century.

Image from Wikimedia Commons