Ukara Island, Tanzania, is one of the most remote places in the world, a scar of parched land jutting above the surface of Lake Victoria, the second-largest lake in the world that to the eye looks like an ocean. Scattered across the tiny island are clusters of mud huts, the places where children go to sleep most nights with empty stomachs.

Ukara is snake-infested, with scarce access to electricity, clean water, food, basic services, or education. Life here offers little, and most of the island’s 22,000 residents dream of escaping to the African mainland in search of something better. But those dreams almost always die, like the signal flare of a stranded sailor—a brief blaze of light that zigzags chaotically into the sea that no one sees.

This island, and the world-forgotten places like it, have become second homes to the Sisters of Mary. They have taken vows to enter these places submerged in poverty and to love the poorest people on earth—where they work hard to save them. The religious order was founded by American Venerable Aloysius Schwartz in Busan, Korea, in the years following Korea’s civil war.

Ukara Island was added to the Sisters’ long list of forsaken landscapes a few years ago when a missionary priest made a desperate appeal to the sisters on behalf of the people living on the water-locked patch of land.

He spoke of suffering, loneliness, of needs unmet—and of a young girl named Jackline. The teenager had been bitten by one of the venomous snakes that was coiled in a dark corner of the family’s small hut. “I asked Mary to save me; but for six months, the venom stayed in me. I couldn’t get out of bed,” Jackline said.

After the priest’s S.O.S., Sisters Maureen and Vaileth boarded a bus in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and began a 28-hour journey by land and sea to reach Jackline and the poor island children. When they boarded a small boat by the coastal town of Mwanza, they didn’t know they would be ferried along with a corpse. When Lake Victoria’s winds began to gust a few hundred yards from the mainland, the boat began to feel thin beneath the sisters’ feet, so they busied themselves by praying for the soul of the dead woman to be buried on Ukara Island.

After deboarding, the sisters sought out Jackline, who hadn’t eaten in a day. “Somehow, the sisters found me,” Jackline said. “When they called my name, it sounded like a miracle. God saved me; the Sisters of Mary saved me.”

After passing an entrance examination, Jackline was admitted into the sister’s Girlstown community in Dar es Salaam, where she began to study alongside more than 800 other teenage girls. She wants to become an accountant who one day can help family and old friends on Ukara Island.

In total, the Sisters of Mary operate sixteen Boystown and Girlstown communities in six countries, where each day more than 380 sisters rise early in the morning to mother poor children back to the joy of life through holistic care: education, Mass, prayer and the sacraments, emotional support, vocational training, food, clothing, and any other need. It is the sisters’ goal to send children out into the world with a strong Catholic foundation and a bright future.

Since their initial visit, the Sisters of Mary have returned annually to Ukara Island. Their most recent recruitment trip came last month, which involved a plane, bus, boat, ferry, and motorcycle to reach their future students.

The day before boarding a ferry to Ukara, two of the sisters met a small boy named Rigobert.

“He looked very simple, poor, and humble,” said Sr. Margie Cheong, who has served the poor in Central America, Mexico, the Philippines, and now Africa. “When we asked where he was going, he replied, ‘I’m going to Ukara Island to take the test with the Sisters.’ We said with a smile, ‘We are those sisters—we’ll see you tomorrow!’ And we did.”

The sisters saw him the next day at 6:30 a.m. Mass, in the same clothing. They smiled at one another.

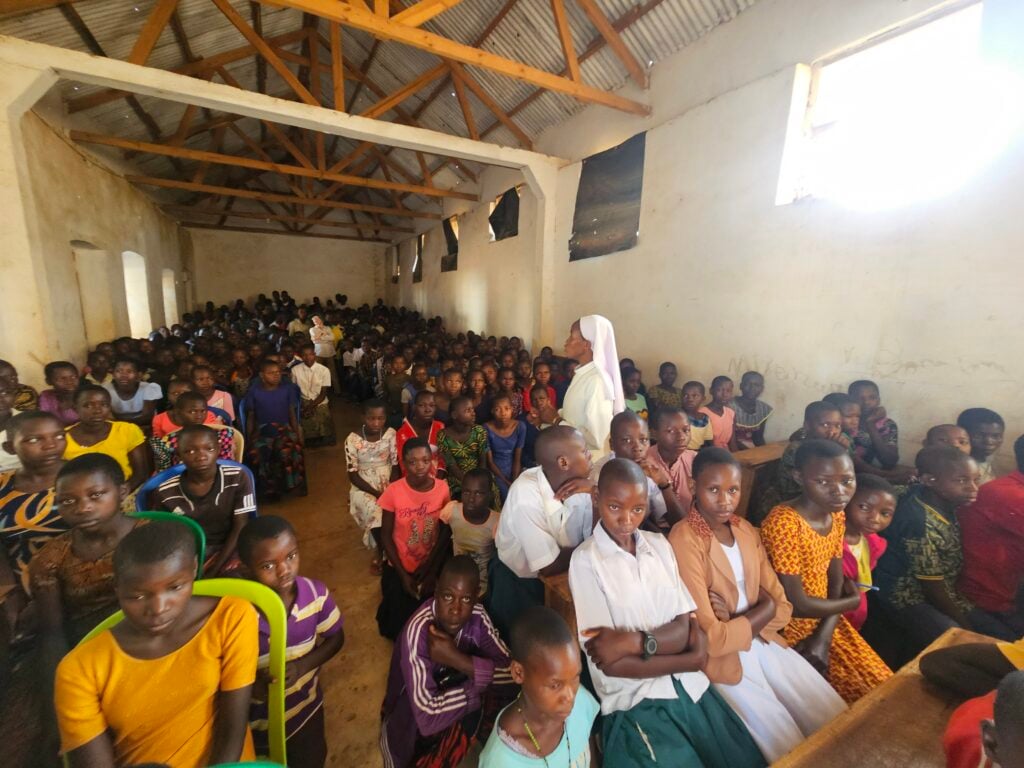

Later in the morning, the sisters were stunned by the large number of children—463—who had arrived to take the examination, hoping for the passing grade that would serve as a passport to freedom from Ukara and into Boystowns and Girlstowns. The children were separated into four classrooms, where they seemed to transmogrify into a mass of one. They sat, shoulder-to-shoulder, taking the exam that rested on old wooden tables.

In her own classroom, Sr. Margie asked eighty children how many of them had eaten breakfast that morning. No one raised their hand. It was the afternoon. Thereafter, the sisters bought 200 packs of biscuits for the students, who began to eat and smile.

In total that day, the sisters selected fifteen children who scored well on the exam. The rest, sadly, will not see the sisters again until 2026, when another test will be administered.

Before leaving, Sr. Margie and the other sisters remembered Rigobert, but they could not locate him. He had scored just below the cutoff point for admittance, but the little boy had pierced Sr. Margie’s heart deeply.

“My heart was not at peace.” she said. “We had no address, no full name—nothing—but I wanted to find him.”

After the final interviews, at around 5 p.m., she called for four motorcycle drivers to begin to take the sisters to home visits. Each nun hopped on a motorcycle with one or two children and began to visit homes on the island. As they neared their last stop, in the middle of a busy village filled with people, children, noise, and the smoke of cooking fires, Sr. Margie saw Rigobert.

She said it felt like a scene from a movie.

Amid the noise of the motorcycle, he was smiling and looking her way.

“I called out, ‘There’s Rigobert!’ I said, ‘I found you! I was looking for you.’ He led us to his home, where we met his grandmother, an 86-year-old woman who could neither hear nor speak. She was sitting on a dirt floor.”

A brokenhearted story began to be explained by neighbors.

Rigobert’s mother died when he was seven; his father died soon after. He lived alone and in poverty with his grandmother, who was too ill to care for him. He had done his best in her helpless state. The sisters also discovered that Rigobert had an eye infection and was unable to see through one eye.

Right there, on the spot, Sr. Margie and Sr. Vaileth decided to accept him into their Boystown community in Dodoma.

“He was truly one of the poorest boys we’ve met. We believe his eyesight can be treated with proper care,” Sr. Margie said. “He has great potential. Rigobert, like so many others, deserves the chance to heal, to learn, and to dream.

“This is my third year helping recruit children for the Sisters of Mary school in Tanzania. I am more convinced than ever that Mama Mary, the Virgin of the Poor, has sent the Sisters of Mary to Africa to love and serve the poorest of the poor, especially those without a mother—just like Rigobert.”

“This is why we are here.”

How to help:

Over the course of the past half century, over 175,000 children have graduated from the Sisters of Mary’s Boystown and Girlstown communities. World Villages for Children (WVC) is a nonprofit organization that financially supports the Sisters as they help children break free from a life of poverty and lead them to Christ. WVC provides food, shelter, clothing, medical expenses, Catholic education, and vocational training to more than 20,000 children in six different countries around the world. To donate to World Villages for Children, please go to https://www.worldvillages.org/poverty/.

Photo from Wikimedia