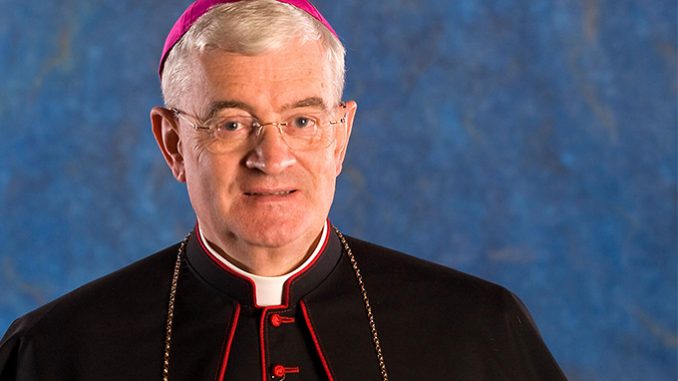

Editor’s note: Bishop Emeritus Peter John Elliott of Melbourne died this past Wednesday, August 6th, at Box Hill Hospital at the age of 81. Bishop Elliott was a convert to the Catholic Church, and was known for his scholarship, catechetical work, and pastoral wisdom. His doctoral studies were at the Pontifical Lateran University in Rome; he was appointed an Official of the Pontifical Council for the Family in 1987. He authored and edited several books for Ignatius Press, including Ceremonies of the Modern Roman Rite, Ceremonies of the Liturgical Year, Liturgical Question Box, Ceremonies Explained for Servers: A Manual for Altar Servers, Acolytes, Sacristans, and Masters of Ceremonies, and The Sexual Revolution: History, Ideology, Power.

———-

I first met Peter Elliott when I was an undergraduate in the 1980s. He was in Brisbane to give a lecture on Catechesi Tradendae, one of the first magisterial documents of the John Paul II era. The one line I remember from that night is: “The warm fuzzies are feeling the cold chills of Polish winds.” He made a friend of me for life with that one comment. I knew exactly what he meant. I was a veteran of the “warm fuzzy” approach to religious education.

For those who missed the 1970s, an RE teacher would come into a classroom with a bag full of pieces of differently coloured fluff with little plastic eyes (aka, warm fuzzies). The bag would then be passed around, and we would each choose a piece of fluff and hand it to a classmate as a gesture of our regard for them. We were also encouraged to write a little note to the person whom we chose to gift the bit of fluff, explaining why we chose them and what they meant to us.

How anyone thought this had anything to do with the Catholic Faith is completely beyond me. The term “warm fuzzies” originated from a children’s story called “The Warm Fuzzy Tale” by Claude M. Steiner, a psychotherapist and promoter of Transactional Analysis. It had zero to do with anything Catholic.

Bishop Elliott was good at making jokes about these hippie-era fads. One of his claims to fame is that he stood for the principle that there should be some significant theological content in religious education. Today, most Catholic educators would find this stance unremarkable, but it was controversial when he and George Pell tried to implement the idea in the Archdiocese of Melbourne at the turn of the century.

It often seemed to me that one of Peter’s problems in getting his ideas taken seriously is that he came from the wrong side of the tracks. His surname was not Irish, or Italian, Polish, or Vietnamese, but solidly British. He was not of convict descent. His father was a High Church Anglican vicar, and the early lines on his CV shout “son of the Protestant establishment”. His secondary school was Melbourne Grammar, an Anglican establishment, and his undergraduate college was Trinity at the University of Melbourne, another Anglican establishment. And then he went to Oxford, the most Anglican of all Anglican establishments, apart from the British monarchy.

In his childhood, Peter had visited the UK with his parents and younger brother, Paul. There, the Elliott family was entertained by C.S. Lewis and his wife Joy Davidman. Joy had two sons from a former marriage, named Douglas and David. Peter always enjoyed telling the story of how Paul disgraced the family by getting into a scuffle with one or other of Joy’s sons. Paul had the typical Australian attitude to dealing with those who think themselves superior–“In your dreams, mate!”

Paul Elliott KC, as he is now, has remarked that his brother Peter was the only boy ever to go to Melbourne Grammar without playing a single sport. Peter so excelled at everything else that he was allowed to bunk off to the library instead of doing his bit on the track and field, or in the pool, or on the river. Notwithstanding this fact, Melbourne Grammar proudly lists Bishop Peter Elliott as one of its top 50 most distinguished alumni.

In Catholic circles, the then-Monsignor Peter J. Elliott made his international name during a decade-long deployment (1987-1997) as an official of the Pontifical Council of the Family. During those years, he earned the esteem of leaders of Catholic family movements around the globe, and he was part of the Vatican’s delegation to the UN Conference in Cairo in 1994. His superior was the Colombian Cardinal Alfonso López Trujillo, a man infamous for delivering long lectures and homilies, often from texts in languages he didn’t know, and that included English. Monsignor Elliott spent a decade bringing some British manners and knowledge of the world’s lingua franca to the work of the Pontifical Council.

In addition to his understanding of the sacramentality of marriage and the Church’s teachings on life issues, both central to his work on the Council, Peter Elliott was known as an authority on liturgy and Church history. At various times, he was a consultor for the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, and a member of Anglicanae Traditiones, the inter-dicasterial commission charged with preparing the liturgical books to be used by the Personal Ordinariates, which Pope Benedict XVI established for Anglican converts to Catholicism.

Like many Anglicans and former Anglicans, Bishop Elliott loved animals, especially cats. The greatest love of his life was some kind of Persian cat named Lady Jacqueline. I say “some kind” because I am sure she was a particular kind, and that merely saying that she was a cat with a lot of grey fur and white paws and a pure white napkin under her chin would be met by Bishop Elliott with a correction, setting me straight about the precise details of her pedigree. Bishop Elliott and Lady Jacqueline were, for a day or so, front page news in Australia when an oil painting depicting the pair and aptly titled “Bishop Elliott and Lady Jacqueline,” was submitted by the artist Yi Wang for Australia’s biggest art prize, “the Archibald”, in 2010. After Lady Jacqueline went to cat heaven, she was succeeded by Lord Justin.

Peter Elliott had the perfect blend of Australian openness to all that is good, regardless of where it is found (we know that a wild brumby can make as brave a horse as a thoroughbred) and an upper-class British “at homeness” with social hierarchies. While some bishops feel embarrassed when addressed by titles such as “Your Excellency”, or in the British Commonwealth, “My Lord” and “Your Grace”. Bishop Elliott was right at home with it. This was not a symptom of arrogance. He was not a puffed-up toad like the character in the Wind in the Willows children’s story, which every British child of his generation would know, but he understood that as a bishop, he was a social dignitary, and he was at ease with his dignitary treatment.

It was so natural for him and for me that I never thought about it until one day when we were both in Rome and I was chatting to some American colleagues at the Santa Anna gate that leads into the Vatican. He arrived near the gate in a taxi, wound down the window of the taxi, and called out, “Tracey, come and open the door for me”! I immediately responded, ducking and weaving my way through the Roman traffic until I got to the taxi, opened the door, stood back with my heels together, and said: “Good evening, My Lord”! It was like a scene from “Downton Abbey” transposed to the Vatican, or so I was later told by those who had witnessed the moment. We proudly held the flag for the British Commonwealth way of doing things together!

Far from being puffed-up, Peter Elliott was one of the kindest people I have ever known. I think if he ever came face to face with the devil, he would give him a cup of tea and say something like “You really are in a mess, aren’t you? Can I help? I could hear your confession”! He was a priest 24/7, and no person, no matter how hopeless the situation, would find themselves turned away when they came to him for pastoral care. He had a reputation for being able to bring people home to the Faith at the last minute and anoint them when they had turned other priests away. He was in his element when doing the kinds of things that only a priest can do.

He called me about one month ago and said that the care at his nursing home was excellent except for the food, which was rubbish, and he was open to offers to be taken to lunch. I suggested a date that didn’t work for him, and so we agreed that I would be in touch again this week. I feel sad that there was no last lunch, but I am happy that he lived long enough to see his contribution to the memoir of his friend Cardinal Pell, published by Ignatius Press. When they were students together in Oxford, they were given the nicknames “the Big Bastard and the Little Bastard”. He was really proud of this fact, even though he was ‘the little Bastard”. I hope that they are now together again, with Lady Jacqueline, and that no dippy angels are passing around bags of warm fuzzies, or if they are, that John Paul II will come forward and say “Enough of that hippie stuff around here!”

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.