Grace Hartigan began her art career free of the past. She had no technical training, education in art history, or particular talent. When she took her first drawing class in 1941 at nineteen, it came as such a challenge that she sweated and cried from nerves.

More than a decade later—after the artist had moved to New York, split from her first husband, joined the Abstract Expressionist scene, and dropped off her son at his grandparents’ house in New Jersey, not sure she would ever care for him full-time again, all in the name of her art—Hartigan finally looked backward. Thus far educated solely in Abstract Expressionism, she figured it was high time she studied the artists that preceded her teachers. “I spent almost all of 1952 painting from the masters—Rubens, Velázquez, Goya,” said Hartigan in an interview.

It is in 1952 that “Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention” begins.1 The marvelous selection of works, at the North Carolina Museum of Art through August 10 and then traveling to the Portland Museum of Art in Maine and the Sheldon Museum of Art in Nebraska, focuses on the artist’s relationships with poets: friendships, collaborations, and inspirations. The show takes special care to note the formal innovations taking place in both poetry and painting at the time. But Hartigan’s use of verse as source material is closely related to her mining of painterly tradition for inspiration, which goes unmentioned. Her work broke from the past, but viewers might like to know that it broke from its Abstract Expressionist present, too.

The show opens with earlier works, many of which feature poets as their subjects. The paintings are heavy, even suffocating, with saturated colors and slashing black, while the marks are kinetic. Though their abstractions may have shocked the average viewer of the time, these canvases were equally controversial among some of Hartigan’s avant-garde peers for their figuration. In Two Women (1954), a portrait of the poet Daisy Aldan and her lover Olga Petroff, Hartigan scumbles baby pink, white, and honey yellow against black, brown, and kelly green. Her faces are schematic, lined in hard black. Across Frank O’Hara’s visage in The Masker (1954) is a horizontal line running over the bridge of his nose and brushing his bottom lashes. These are the artist’s close friends, but she makes them magnetically alien.

The same uneasiness arises in Masquerade and Grand Street Brides, both painted in 1954. Across these monumental paintings—both over six feet tall and seven feet in width—are arrays of costumed figures. Masquerade shows Hartigan and her poet friends, with corresponding photographs reproduced on the wall label; Grand Street Brides depicts mannequins in a bridal-shop window. Which are human beings and which are plastic would be impossible to know without the labels. The Whitney acquired Grand Street Brides, perhaps Hartigan’s best-known painting, in 1955. The purchase was funded by the poet James Merrill, a member of Hartigan’s cadre (he’s featured in Masquerade), whose father, helpfully for Hartigan, cofounded Merrill Lynch. Merrill pops up throughout the show as a prime mover in getting Hartigan’s work into public collections.

Whereas most of the early pictures look like they’ve been painted with colors straight out of the tube, mixed and muddied on the canvas, the still life Artificial Flowers and Apples (1952) stands out for its subtle earth tones: ecru, burgundy, olive. It shares with the other works the gestural, energetic brushwork, but its colors, depth, and composition recall some of Hartigan’s Old Master studies, suggesting that she dutifully assimilated those influences before returning to her own work.

Beginning in 1958, there’s a palpable shift in the works: less frenetic, more sober; fewer depictions of poets, more of their poems; less bankrolling by poets, more gifts to them. The paintings rely on new colors—blood red, French gray, violet—and are built-up and crusty with oil paint, their intrigue coming from texture more than action.

The second gallery tracks Hartigan’s friendship with Barbara Guest, a New York School poet born in North Carolina. Next to several of the paintings, Guest’s poems are reproduced. In Hartigan’s Snow Angel (1960), a flutter of purple over white, a field of gray, and a subterranean, smoldering red translate fragments from drafts of Guest’s poem “Snow Angel”— “violet wings in the white grey snow,” “Angels are grey,” “underground fires are lit”—literally onto the canvas. The wall labels write that this is “reverse ekphrasis,” though perhaps it is as much a continuity as a reversal. Hartigan’s predecessors in the practice include Rubens, whose Venus and Adonis, depicting an episode from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, she painted a copy of in 1952. She was hardly the first painter to have painted from poetry, even if the verse of her age was lyric and freeform rather than epic and mythical.

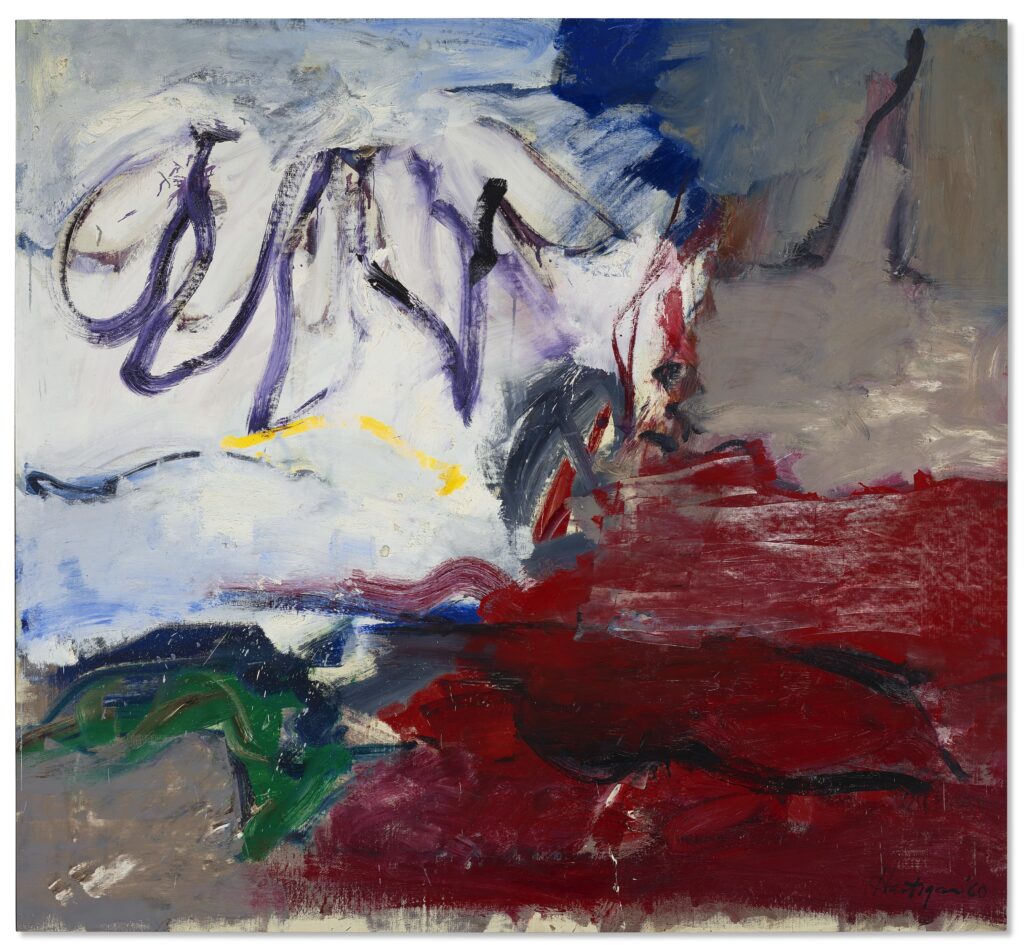

Besides, Hartigan and Guest drew from ancient myth, too. One poem–painting pair is Guest’s “Dido to Aeneas,” from her 1962 Archaics (a volume inspired by the Aeneid), and Hartigan’s Dido (1960). (Guest’s poem is also a nod to Ovid’s faux-epistle of the same name, in the Heroides.) In Dido, between fields of red, gray, and Mediterranean blue lies a central white column of paint, dotted with short, spitting red brushstrokes, and above it an ambiguous black horizontal shape, maybe a body offering itself to the pyre. Skinny yellow splats rain from the white and red.

Hartigan also produced a series of lithographs for an edition of Guest’s Archaics. Like the later paintings, these revel in texture: brush mark, crayon, scraping, drip. The lithographs are part of a large section of the show made up of works on paper that responded to or accompanied poems, not only by Guest but also by Frank O’Hara, Hartigan’s most famous poet friend, and by James Schuyler, whose poems Hartigan admitted she hadn’t read before producing the somewhat generic screenprints on display. Each medium—from collage and ink to oil, lithograph, and screenprint—is strikingly different in Hartigan’s hand.

It is sure that the works on display, especially the paintings, are innovative as well as mesmerizing. But “The Gift of Attention” seems hesitant to mention, and sometimes even apologetic for, the fact they didn’t just come out of the ether. Perhaps this is appropriate to Hartigan’s spirit: her paintings Pallas Athena—Earth and Pallas Athena—Fire (both 1961) are here accompanied by a quote: “I think I chose Athena for myself because she was full-blown from the head of Zeus. She’d had no nurturing, and she was an intellectual goddess.” But Hartigan nonetheless sought ancient precedent for her pastlessness. So, too, does the work in this show take root in the old—in gesture, composition, and poetic inspiration—at the same time that it forges something new.

-

“Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention” opened at the North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, on April 12 and remains on view through August 10, 2025. It will also be seen at the Portland Museum of Art, Maine (October 10, 2025–January 11, 2026), and the Sheldon Museum of Art, Nebraska. ↩