Emma was finally making progress. At 15, she had already been through multiple treatment programs, attempted suicide at 12, and endured sexual abuse by an adult caregiver. Her adoptive parents had tried nearly everything. When her drug use and risk-taking became too dangerous to manage at home, they enrolled her in Re-Creation Retreat (RCR), a small therapeutic program for teen girls in Fredonia, a rural town in northern Arizona.

Emma—whose name has been changed to protect her privacy—had been at the program for just a month. She was adjusting well, beginning trauma-focused therapy, and building rapport with her therapist when, in early June, the Arizona Department of Health Services (ADHS) abruptly shut RCR down.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Families were given just 36 hours to retrieve their daughters. Like all the others, Emma’s family lived out of state. “She was finally making progress,” her mother said. “Now she’s completely destabilized.”

Since getting transferred to a new facility in Utah, Emma has refused food, escaped from the program, spoken to her parents only once, and been placed in safety holds—physical interventions used to prevent self-harm or aggression—as often as six times daily.

Emma’s parents are among many now speaking out against what they see as a reckless and unjustified shutdown. According to RCR’s clinical director, Randy Soderquist, all 19 families with daughters enrolled at the time of closure supported the program. Nine spoke with City Journal and corroborated that view. They say the state acted on thin evidence, failed to consult families and treatment providers for necessary context, and responded to pressure from activists and unverified complaints—upending fragile lives in the process.

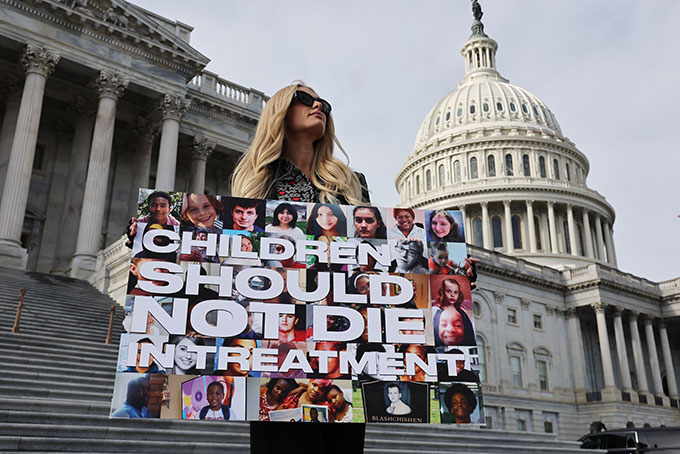

The closure of RCR is part of a nationwide backlash against youth residential treatment, where adolescents live in a group setting and receive 24-hour care for serious emotional or behavioral challenges. The backlash has been encouraged by socialite Paris Hilton’s high-profile campaign against the so-called “troubled teen industry.” Hilton’s efforts, amplified by sensational media coverage, have prompted regulators to act quickly and aggressively. While some closures may have been warranted, others, like RCR’s, shuttered longstanding programs with strong reputations, leaving families like Emma’s scrambling to help their kids.

Founded in 2009, RCR served more than 800 girls over its 16 years of operation. Randy Soderquist and his wife, Toni, started the small, family-owned program after their daughter faced mental-health challenges. They created RCR to support families with similar struggles.

RCR offered clinical therapy, education, and life-skills training in a highly structured setting. Its therapeutic model emphasized resilience over a victimhood mindset. Girls participated in equine therapy, outdoor hikes, yoga and dance classes, and volunteered at a local animal shelter. Over the years, residents became part of the fabric of Fredonia, regularly taking part in community events.

Parents I spoke with hand-selected RCR after exhausting local and less intensive options. They praised the program’s transparency and emphasis on family engagement: daily updates through a parent portal, weekly Zoom Q&As, and parent training seminars. Several credited it with saving their daughters’ lives.

For 16 years, RCR operated largely without serious incident. When minor violations arose, typically administrative in nature, the ADHS issued citations that the program promptly addressed. Just three months before its sudden closure, RCR passed its annual state inspection and earned independent accreditation from CARF, a national credentialing body.

But RCR came under scrutiny after Inside Edition aired a segment on May 25 featuring emotional accounts from former residents, many of whom are now activists working to shut down such programs. The coverage omitted critical context about why the program exists, the behaviors that led to placement, and the constraints of treating minors in crisis. Within days, compliance officer Lisa Rice conducted a surprise inspection.

Rice arrived on June 5 and spent nine hours at RCR, according to staff. They said her demeanor—dismissive, agitated, and disruptive—was markedly different from her earlier visit in March. According to staff, interviews were conducted in groups, and Rice made phone calls during them. Standard practice typically requires private, one-on-one interviews with minors in potential abuse cases.

By day’s end, ADHS had issued an emergency license restriction, citing an “immediate danger” to patient safety. According to a police report obtained by City Journal, when Fredonia Police arrived, Rice referenced the media attention, telling officers, “Insider Edition [sic] did a special on this facility, it’s been getting a lot of media attention.”

According to the police report, Rice described RCR’s point-based behavioral model as abusive, calling it “tortur[e],” referencing “a lot of retaliation tactics,” and describing what she believed to be “a lot of . . . institutional abuse going on”—language that closely mirrors activist rhetoric. Point-based systems, where students earn privileges by meeting treatment goals, are a standard feature of licensed residential care. That a licensing official appeared unfamiliar with such a foundational therapeutic approach alarmed both professionals and parents.

Rice told officers that all six girls she interviewed alleged sexual or physical abuse. But one of those girls, River, told City Journal that she made no such claim. Her only concern was that some safety holds occasionally had been applied inappropriately, though she emphasized that most were necessary. River said Rice asked leading questions and seemed intent on shutting the program down.

The most serious allegation in the police report—sexual abuse by a staff member—was later retracted in a notarized statement. Another claim about inappropriate restraint was also withdrawn, according to the mother of one of the girls whom Rice interviewed. None of the 22 parents and guardians contacted by police consented to forensic interviews for their daughters or supported any effort to pursue prosecution.

Rice also told officers that some of the girls had visible bruises. But when police officers returned the next day, each girl denied having any current bruises. Rice declined to sign a witness statement, refused to provide notes, and left the scene abruptly, leaving officers and clinicians unsure who was responsible for supervising the minors. ADHS ultimately told police that Soderquist would determine where the girls should go.

“How does it work that the people being accused of the abuse are now responsible to find the homes?” asked Susann Clinton, a nurse practitioner from the Safe Child Center who was contacted by police for support.

Police also contacted the Department of Child Safety (DCS), but it lacked jurisdiction to assist with emergency placements. DCS noted that, while previous allegations had been made against RCR, “those were not substantiated.”

With no clear direction from state officials, police left. Despite being stripped of their authority, RCR staff claimed to have stayed overnight to supervise the girls until emergency placements could be arranged. Staff later described the evening as “complete chaos.”

Families wanted answers. If the facility truly posed an imminent safety risk, as ADHS claimed, why were the girls left there? Many said their calls to the licensing department were met with dismissal, prompting them to reach out to state senators and the media.

The fallout was swift. Nineteen out-of-state families were given just 36 hours to arrange new placements, travel, and cover tuition and enrollment costs—resulting in thousands of dollars in expenses. A few girls returned home, but most were transferred to other programs. Many parents said their daughters regressed. Emma spiraled.

Her mother holds on to hope. “We’re not giving up. We believe in her. But this was a huge, unnecessary setback.”

ADHS, which did not respond to multiple requests for comment, later cited RCR for multiple alleged violations—many of them minor or easily explained, had parents or providers been consulted. Several parents relayed that their daughters had a history of making false abuse claims, important context they felt should have been considered.

Among the citations were the program’s supervised-communication and limited-phone-access policies, both standard safety measures in residential care. “My daughter once learned self-harming behavior from another peer,” said parent Ashley Miller. “I didn’t want her having unsupervised conversations.”

RCR was also cited for unauthorized use of resident labor, for assigning daily chores that parents claim to have explicitly approved. A more serious-sounding violation involved a former employee whose fingerprint clearance was denied due to a charge mistakenly flagged as child abuse. According to the program director and the employee in question, the issue stemmed from a seven-year-old DUI charge; staff said that Rice declined to review documentation correcting the record.

“This didn’t need to happen,” said one parent, echoing the view expressed by every family contacted. “If the state had done its due diligence instead of reacting to a media-driven panic, our daughters wouldn’t have been pulled out of a program that was helping them.”

Parents argue that critics of residential care often have no sense of the desperate situations that lead to these placements. “My daughter’s behavior was so dangerous,” one father said. “It’s a miracle she wasn’t dead or trafficked.”

Some of RCR’s most vocal critics, Soderquist said, were former students who had once expressed gratitude. Seeing the work he once took great pride in publicly condemned, he said, has been deeply painful.

But not all former residents share those criticisms. Three 17-year-old alumni of RCR spoke with City Journal. Each pushed back against the shutdown and media portrayals of the program as abusive. And though the adjustment was difficult at first, as it is for many in these settings, each credited RCR with helping them when nothing else had.

River, who had nearly completed the program when it shut down, returned home with her parents’ support. “I was in a really bad place when I got there, and I’m a completely different person now,” she said. “Personally, I think it really benefited me. Eventually, I kind of grew to love the place.” River also believed some allegations were made strategically by girls hoping to be sent home.

Skylar, who is now preparing for college, also defended the program. “The Inside Edition segment makes it sound a lot worse than it actually was because it’s missing context,” she said. She acknowledged RCR had faults, like uneven rule enforcement and staff favoritism. But she views her time there as a necessary intervention that helped prepare her for the real world. “I didn’t like the place, but I’m grateful that I went,” she said. “It’s not meant to be summer camp.”

Nella, who completed the program last year, was dismayed to learn that complaints she had made early in her treatment—one about restricted bathroom access during meals, which she later understood was a safety policy, and another concerning inappropriate behavior from a roommate—were cited by the state. She felt staff had handled the situations appropriately, and she never intended for her comments to be used against a program she ultimately credited with turning her life around. By the end, Nella was enjoying herself. “I actually was having a lot of fun,” she recalled—especially during equine therapy, where she had the chance to work with baby horses. She, too, is now preparing for college.

“RCR has helped so many girls,” said Nella. “Residential programs are extremely helpful for families who’ve done everything they can.”

While a few negative stories have been amplified by the media, the experiences of girls like Nella, River, and Skylar are far more common, though rarely acknowledged in mainstream coverage. Those who try to challenge the dominant narrative can face retaliation. After Ashley Miller publicly defended RCR online, an activist contacted her employer in an apparent attempt to jeopardize her job.

Meantime, families are losing options. The number of residential treatment programs has declined sharply. That’s not because of mounting evidence of abuse but because of activist-driven narratives, sweeping legislation, and regulatory overcorrection.

Re-Creation Retreat is the latest casualty of a system increasingly shaped by public panic rather than sound judgment. The Soderquists are appealing the state’s decision. But they’re nearing retirement and don’t plan to reopen. The regulatory climate, they believe, has made their work untenable.

Unless the campaign to dismantle residential care is tempered by reason and a clear-eyed look at the evidence, more programs will disappear—and the neediest children will be left with nowhere to go.

Top Photo: Justin Paget / DigitalVision

Source link