So many surprising and absurd stories have come out of the 2025 New York City mayoral election that it’s hard to know where to start. But one overlooked absurdity is the notion that Brad Lander has been a good—or even competent—city comptroller.

In that role, Lander oversees $288.59 billion in assets, including the city’s budget and, more critically, the five pension funds that support New York’s public safety workers, teachers, and civil servants.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

How has he done? Since Lander took on the role in 2022, the pension funds have returned less than 3 percent annually—during one of the strongest bull markets in living memory.

Such disappointing performance might be forgivable if Lander had reduced risk by shifting assets into safer, lower-yield investments. Instead, he managed to deliver both weak returns and greater exposure to risk.

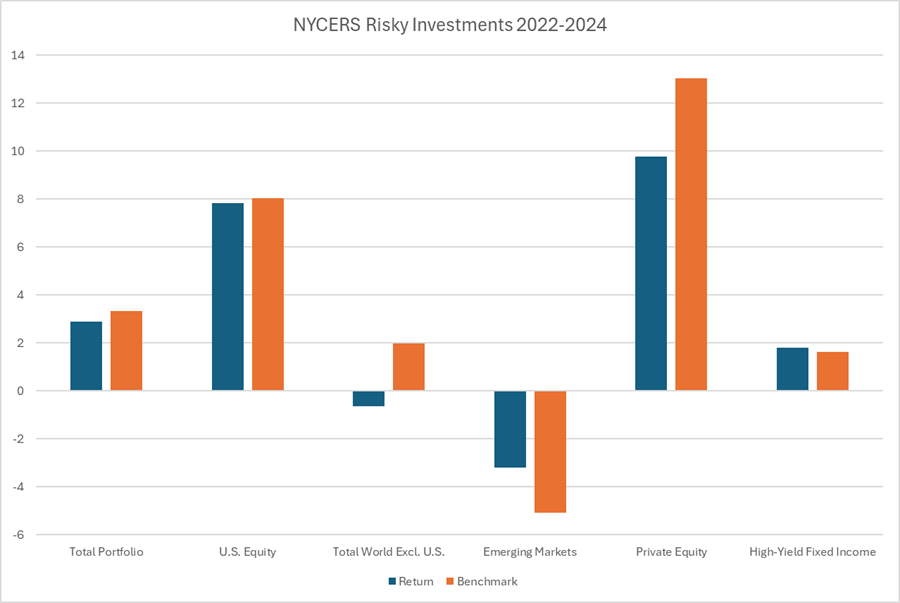

Almost every risky asset class has underperformed its benchmark, published in the annual financial report, during Lander’s tenure. The figure below depicts the realized returns compared with the benchmark for one of the largest funds, the New York City Employees’ Retirement System (NYCERS).

True, it can be unfair to judge performance based on just a few years of returns. Some strategies that lag in one type of market perform better over the long run. It’s possible that Lander’s investment approach might outperform the benchmark in a downturn.

But that seems unlikely, because Lander not only took on more risk but also put political objectives ahead of returns. He moved more funds into investments that fulfilled ESG standards, divested from fossil fuels, diverted money into local affordable-housing projects, and has chosen not to reinvest in Israeli bonds. No clear economic justification exists for any of these decisions.

Basic finance teaches that constraints reduce returns. That reality hurts both public-sector retirees and the taxpayers who must make up the difference when pensions underperform. ESG investing might have seemed like a good choice in 2019, when it appeared to be a good investment because it overweighted tech stocks. But fiduciaries have no excuse today.

Lander’s decision to boost investments in private equity is equally hard to defend. Many public pension funds have done the same over the past 15 years, drawn by the promise of higher returns. The logic is that, since pension liabilities are long-term—payments don’t begin until workers retire—funds can afford to hold illiquid assets and earn a premium for doing so.

But private assets lack clear, objective market values. That gives managers leeway to assign valuations that make pension funds appear better funded than they are, at least until the investments mature and reality catches up.

However, in many cases, the promised illiquidity premium has not paid off. Pensions funds are now finding that their private-equity investments underperformed as they matured. Many pensions aren’t able to get their money back when they need or expect it. New York City’s private-equity investment return last year was only 5.1 percent, much lower than the more liquid and transparent public market.

The fees for private equity are also very high. NYCERS paid $141 million in fees to private equity in 2024 for mediocre returns. Private equity represented just 10.7 percent of the fund’s portfolio but accounted for nearly 30 percent of all investment fees. Yet last year, the city increased its exposure and long-term target.

This problem goes beyond Lander—expanded investment in private equity required legislation from Albany—but Lander is responsible for making recommendations for the funds. And he has not come out publicly against this approach—except when it comes to fossil fuels, of course.

Equally baffling is Lander’s recent decision to sell $5 billion of the retirement fund’s private-equity stake in the secondary market for portfolio “strategic realignment” purposes. It’s unclear precisely what the city is realigning for. It’s equally unclear whether the pension funds gained or lost money on the deal (many lose out in the secondary market).

Whether one looks at his record from a short-term or long-term perspective, then, Lander’s tenure as comptroller is no success.

Photo by CHARLY TRIBALLEAU/AFP via Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link