The Soviet Union’s Forgotten Mars-Venus Mission

The USSR’s ambitious space exploration plans foundered due to the lack of a viable rocket system.

We’re almost four decades away from the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. Since the United States was the triumphant party in that conflict, we often forget that there was a time when the Soviet Union actually worried the Americans. This was not just because of their massive nuclear weapons arsenal, large army pointed at the heart of Europe, bellicose rhetoric, or revolutionary ideology. Americans also feared Soviet military technology.

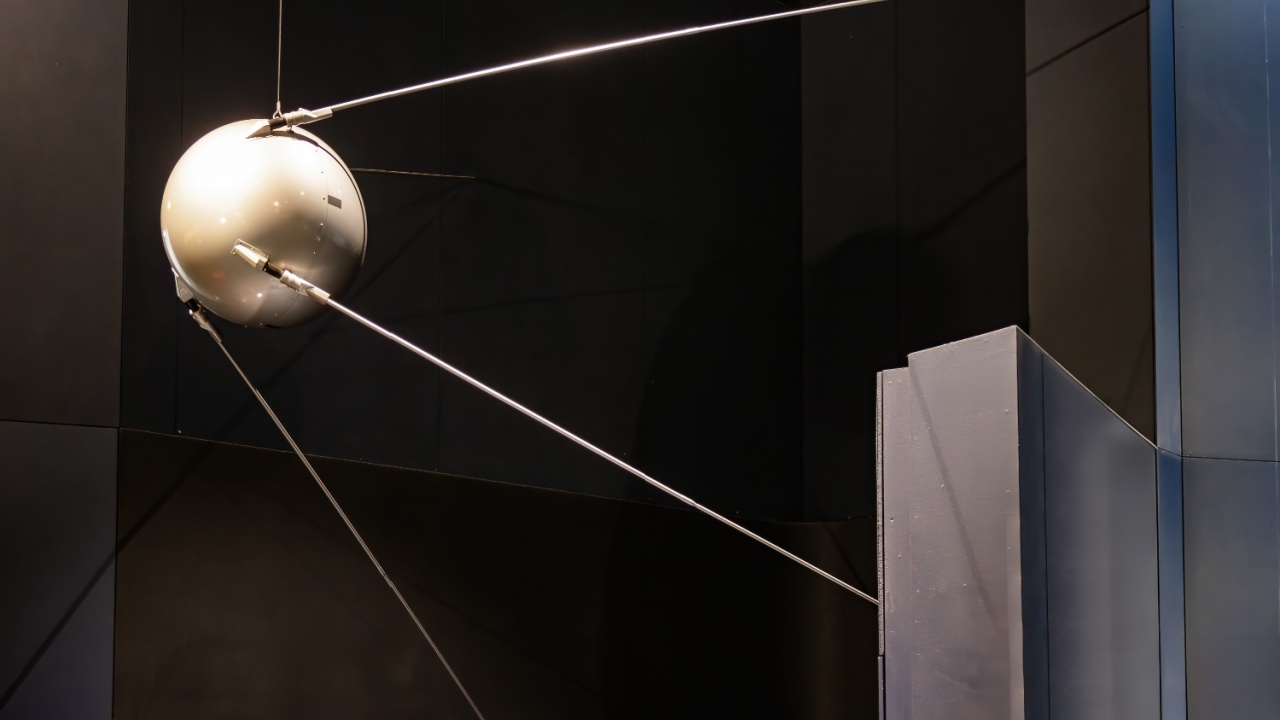

In the strategic domain of space, the Soviets were very competent for many decades. Not only did they achieve major victories in the Space Race, but the Soviets also had grand ambitions to spread their communist ideology to the stars. Yes, Moscow planned to put cosmonauts on the moon and Mars. Moreover, the Reds intended to send their ships and people throughout the solar system—long before their American rivals could do so.

The Soviet Union’s Heavy Interplanetary Vehicle

That’s where the USSR’s Heavy Interplanetary Vessel (TMK) comes into the picture. Conceived during the height of the Space Race of the Cold War, the TMK program endeavored to send crewed missions to both Mars and Venus, marking a bold response to the Americans’ precise lunar ambitions. The TMK series never progressed beyond the design phase. However, its conceptual innovations, engineering challenges, and historical context offer a fascinating glimpse into the Soviet Union’s aspirations for interplanetary travel.

Spearheaded by the OKB-1 Design Bureau, under the leadership of both Sergei Korolev and his deputy, Mikhail Tikhonravov, the project aimed to leapfrog the Americans, who were focused on reaching the moon while showcasing Soviet technological and scientific prowess. The TMK series consisted of multiple spacecraft. Instead, it was a family of proposed designs—including the TMK-1, TMK-E, MAVR (Mars-Venus), and KK (Space Complex for Delivering a Piloted Expedition to Mars).

Each variant addressed different mission profiles, ranging from flyby missions to Maris and Venus to more complex scenarios involving landings on the Martian surface. The project’s roots can be traced back to an earlier concept, the Martian Piloted Complex (MPK), which was proposed in 1956. That mission required a massive spacecraft to be assembled in low-Earth Orbit (LEO) for a Mars landing mission. The failure of the MPK mission was tied to the failure of the N1 heavy-lift rocket. Without that rocket, the spacecraft could not be assembled in LEO; no assembly in LEO meant that no mission was going to take place.

Like the MPK program, the TEK series was meant to leverage the N1 rocket. The N1 was critical to the TMK’s success, as it was tasked with placing the 75 metric tons (165,347 pounds) TMK-1 spacecraft into orbit. As the baseline design for the TMK series, TMK-1 was envisioned as a crewed spacecraft carrying three cosmonauts on a three-year Mars flyby mission, launching on June 8, 1971, and returning to Earth on July 10, 1974.

TMK-1 would follow a free-return trajectory, using Mars’ gravity to slingshot back to Earth, requiring only minor mid-course corrections. During the flyby, remote-controlled probes would be deployed to the Martian surface to collect data, compensating for the lack of a landing.

To Go Where No Commie Has Gone Before

The TMK-1 included several key components: a command center for piloting, living quarters, and a life support system to sustain the crew for the three-year journey. The spacecraft was equipped with solar panels and a reentry capsule for the crew’s return to Earth.

A notable variant, the TMK-MAVR (Mars-Venus), incorporated a Venus flyby on the return leg, reducing the mission duration. This design aimed to maximize scientific return by studying two planets in a single mission.

There was also the TMK-E variant, which explored the use of nuclear electric propulsion, a cutting-edge technology at the time. Another giant in Soviet engineering, Konstantin Feoktistov, proposed that the TMK-E would spiral out of Earth’s orbit using an ion drive powered by a nuclear reactor, minimizing exposure to the Van Allen radiation belts. Once beyond, the TMK-E, which would be slower than its sister variants, would use conventional rockets.

TMK-E’s design introduced a distinctive feature of Soviet interplanetary concepts: a long boom separating the nuclear reactor from the crew quarters to reduce radiation exposure.

But the most advanced iteration of the TMK series was the KK Space Complex. Proposed in 1966, the KK included multiple modules, such as the Expeditionary Spacecraft (EK) for command-and-control, an Orbital Complex (OK) for living quarters, a Landing Module (SA), an Ascent Module (AV), an Ascent Rocket stage (RV), and a Planetary Station (PS) for surface operations. This design reflected the Soviet Union’s growing ambition to achieve a crewed Mars landing, planned for a 1980 launch.

A Hard Lesson for America’s Space Program

Sadly for the Russians (and thankfully for the Americans), the TMK program never made it off the drawing board. Just as their MPK program for going to Mars proved to be the undoing of their manned deep space exploration program, the Soviets’ lack of a proper heavy-lift rocket sank their manned deep space exploration program.

But there is a warning (or at least a hard lesson) to be learned from the failure of the Soviet N1 rocket program for the current American space program. If you cannot launch your astronauts beyond Earth’s orbit, no amount of theorizing will enough to ensure your highfalutin plans can leave the drawing boards.

About the Author: Brandon J. Weichert

Brandon J. Weichert, a Senior National Security Editor at The National Interest as well as a contributor at Popular Mechanics, consults regularly with various government institutions and private organizations on geopolitical issues. Weichert’s writings have appeared in multiple publications, including The Washington Times, National Review, The American Spectator, MSN, The Asia Times, and countless others. His books include Winning Space: How America Remains a Superpower, Biohacked: China’s Race to Control Life, and The Shadow War: Iran’s Quest for Supremacy. His newest book, A Disaster of Our Own Making: How the West Lost Ukraine, is available for purchase wherever books are sold. He can be followed on Twitter @WeTheBrandon.

Image: Agsaz / Shutterstock

The post The Soviet Union’s Forgotten Mars-Venus Mission appeared first on The National Interest.