Corn Syrup Usurped Sugar—But Not Because of Tariffs

President Trump says he got Coca-Cola to agree to replace high-fructose corn syrup with real cane sugar in its flagship American soda. The company hasn’t confirmed the full extent of the change, but just the announcement was enough to send corn refiners into panic mode and free-trade purists into smug mode.

Cato’s Scott Lincicome fired off a typical series of condescending tweets: “Anyone want to tell Tariff Man why Coke puts corn syrup in the worse US version? Spoiler… sugar protectionism.”

Mark Perry, an economist who is an AEI emeritus scholar repeated the same party line.

This really is a party line. It’s the sort of thing you used to get instructed in when you showed up in Washington, DC, as a bright young conservative or libertarian and attended think tank talks. Perhaps it still is (it’s been quite a while since we broke bread with the fading D.C. “conservative movement”). It was a useful line for the well-fed right in D.C. because it attacks tariffs and an unpopular type of farmer (sugar plantations have had a bad reputation for as long as we can remember) while leaving foreign policy interventionism and the genuinely powerful Midwest farm lobby untouched. It makes the rise of corn syrup out to be the fault of the thing the bipartisan establishment hates more than almost anything: the protection of American producers from foreign products dumped on U.S. consumers.

The problem is that it’s just not true.

Yes, America has long protected its sugar industry. But that’s not why Coke switched to corn syrup in 1984. The real story is more revealing. Corn syrup took over American food not because sugar was too expensive, but because corn was made artificially cheap. That wasn’t a market decision, and it had nothing to do with protecting domestic producers from foreign competition. It was Cold War policy, farm-state politics, and a technological breakthrough rolled into one.

The Long Shadow of Sugar Protection

The United States has shielded its sugar industry since the 1934 Jones–Costigan Act, part of the New Deal’s attempt to stabilize commodity markets during the Great Depression. The law created quotas, price supports, and marketing allotments to keep domestic sugar prices high and protect farmers from the volatility of global markets.

Those protections were later layered with tariff-rate quotas that limited cheap cane sugar imports from places like Brazil and the Caribbean. Prices stayed high but stable. For decades, this created a two-tier system: cheap global sugar for the rest of the world, and more expensive, protected sugar at home.

After World War II, the U.S. participated in the International Sugar Agreement, an effort to coordinate supply and price among producing nations. But that collapsed in 1981, flooding the world market with sugar and crashing global prices. President Ronald Reagan—who the D.C. establishment loves to pretend was a die-hard free trader rather than a more pragmatic free-market economic nationalist—responded by tightening U.S. import quotas in 1982, reinforcing domestic protections.

Critics love to point to those sugar barriers as the reason for the rise of corn syrup, but the protections had been in place for decades. If tariffs were really the problem, why didn’t Coke switch to corn syrup in 1955?

What Changed: Subsidies and Innovation

The timing matters. Coca-Cola made the switch in 1984, not in the 1930s, 1950s, or even during the sugar price spike of the 1970s. All along through those years, there were sugar alternatives available. But Coke stuck with sugar despite the high price.

What changed wasn’t sugar policy but a new combination of two forces. First and most important, we had government policy—mostly advanced by Republican presidents—that massively subsidized corn, flooding the U.S. with cheap grain. Second, a technological breakthrough that made it possible to turn that surplus corn into a sugar substitute.

In the 1960s, Japanese scientists developed the enzyme glucose isomerase, which allowed food scientists to convert cornstarch into high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS). By the mid-1970s, the process had been commercialized. HFCS was cheaper than sugar, more shelf-stable, and worked well in beverages and processed food. But what really made it irresistible was the government-engineered collapse in corn prices.

The Man Who Told Farmers to Get Big or Get Out

The story starts in 1972, when President Richard Nixon struck a landmark grain deal with the Soviet Union. The U.S. would sell millions of tons of grain to Moscow to support détente, our policy of trying to make nice with the Soviet communists. To meet that demand, Nixon’s Secretary of Agriculture, Earl Butz, tore up the old supply controls that paid farmers to leave land fallow.

Butz’s message was simple and brutal: “Get big or get out.” Plant corn “from fence row to fence row.” Instead of propping up corn prices by depressing production, Washington would directly support grain production with subsidies, crop insurance, and loan guarantees.

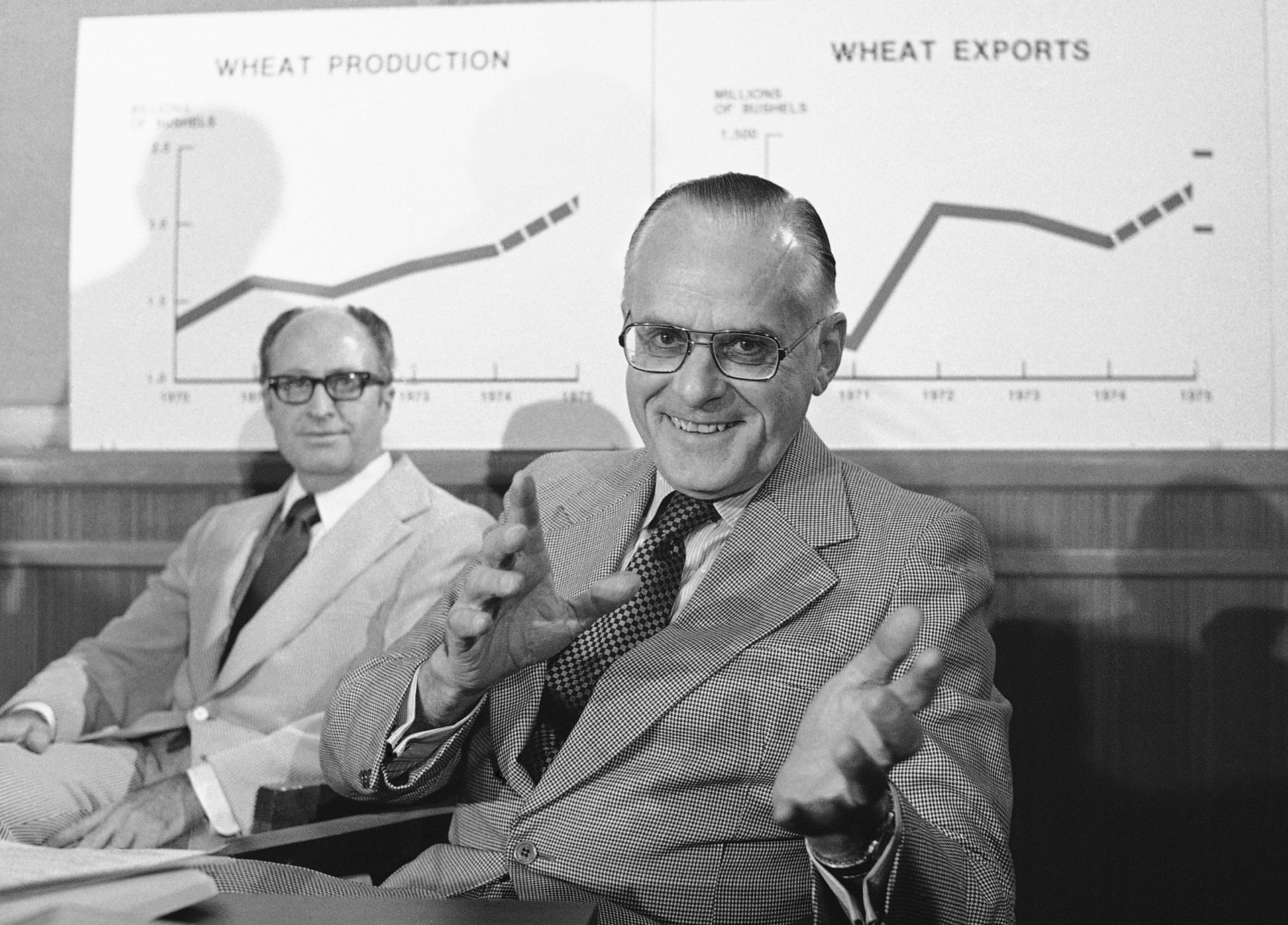

Agriculture Secretary Earl Butz speaks to the press in Washington, DC, on August 12, 1975. Butz said that he had asked U.S. Grain Traders ” to refrain from further negotiation” with the Soviet Union until the government has a better idea of the final corn harvest. (AP Photo/Charles Bennett)

Corn production surged. Prices rose temporarily. But the system was built on unstable geopolitics.

Then Came Afghanistan—and the Crash

In December 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. President Jimmy Carter responded by imposing a grain embargo, abruptly cutting off Soviet demand. Corn prices collapsed. Farmers who had gone deep into debt to expand during the boom years faced financial ruin. This was exacerbated by the high interest rates that resulted from Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker’s campaign to crush inflation. Land values tanked. Equipment was repossessed. Suicide rates climbed in the heartland.

The federal government responded the only way it knew how: more subsidies. Corn became a guaranteed crop. Growing infinite corn was profitable not because of market demand, but because Washington paid farmers to grow what it couldn’t sell abroad.

Meanwhile, food companies had just acquired a shiny new industrial use for that excess corn: HFCS.

By the early 1980s, corn syrup wasn’t just cheap. It was the cheapest calorie on earth. That’s when Coke and Pepsi made the switch. Corn syrup conquered soft drinks not because sugar got more expensive, but because corn got artificially cheap.

A Cultural Rebellion: Rain on the Scarecrow, Blood on the Plow

The same farm policies that created corn syrup also triggered a national crisis in rural America. Small towns were hollowed out. Family farms were swept up by banks in foreclosures and sold off to big agribusiness. In 1985, musicians Willie Nelson, John Mellencamp, and Neil Young launched the first Farm Aid concert to support struggling farmers and challenge the policies that destroyed family farms while enriching agribusiness.

John Mellencamp’s “Rain on the Scarecrow” became the anthem of that era. Released the same year, it captured the heartbreak of generational loss and the fury of farmers abandoned by Washington.

“Rain on the scarecrow, blood on the plow / This land fed a nation, this land made me proud.”

The music video for “Rain on the Scarecrow” begins with a conversation with three young farmers somewhere in the Midwest. It echoes all the themes we’ve been discussing: the collapse of farm prices, the embargo, the sudden changing of the laws, and unaffordable loans.

“Well, all the government wants to talk about, they want to keep giving more loans and more loans. That all—it seems like that’s all they’ve got in their head. We don’t need another loan. We need a good price. Just another farm loan, that’s just another payment we gotta make and we can’t afford to do that,” one of the farmers says.

“I think the politicians are playing games with us. It don’t cost them anything to change the rules and embargo another country,” another says.

“All they want is cheap food, and I can see that. But they don’t take the farmer into consideration at all,” the first fellow says. (The third remains silent.)

Trump’s Sugar Reversal: A Symbolic Correction

If Trump has truly convinced Coca-Cola to return to cane sugar, he’s doing more than fixing a recipe. He’s shining a light on one of the most misunderstood economic shifts of the late 20th century.

The move to corn syrup wasn’t caused by a “Tariff Man.” It was caused by Cold War diplomacy, subsidized overproduction, and a technological leap that turned surplus grain into shelf-stable sweetener.

The free-trade crowd loves to blame tariffs for anything they can. But in this case, it wasn’t a market distorted by protectionism. It was a market engineered by the government’s abundance policy and its whipsaw Cold War policies.

You can see why this is awkward for the D.C. establishment. It was our interventionist foreign policy—first détente and then grain embargo—coupled with aggressive promotion of international trade and corn subsidies that brought about the dreaded rise of corn syrup and the exile of cane sugar. That’s not a story that is useful to their policy agenda.