Last week, the New York City Charter Review Commission announced that it was considering a “top-two” system for mayoral elections, whereby the two candidates receiving the most votes in an open-to-all-voters qualifying round advance to the general election. As a political scientist, I don’t love the proposal, but it could work—if parties retain control of which candidates use their labels.

Currently, New York uses ranked-choice voting (RCV) in party primaries—a system in which voters rank candidates by preference, and votes transfer until a winner emerges. For general elections, the city uses a single-vote system. The commission’s proposal would make two key changes. First, it would replace party primaries with a nonpartisan winnowing round using RCV—what advocates call an “open primary” even though it does not select party nominees. Second, it would advance only the top-two candidates to the general election, effectively creating a runoff.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Many political scientists are wary of the “top-two” system spreading beyond the states where it’s currently used: California, Nebraska, and Washington (plus Louisiana, depending on one’s chosen taxonomy). Most agree that its biggest flaw is the possibility of a general election between two candidates of the same party.

From there, critics diverge. Some argue that the system undermines democracy, which they claim requires a choice between two parties. Others suggest top-two reduces voter turnout. Still others note that the scheme effectively excludes minor parties from general elections. Analysts also question the evidence of the system’s moderating effect.

The current system has its own problems. New York City appears headed for a four- or five-way mayoral race in November. That could change in the coming months, but if it doesn’t, several candidates will likely split the same constituencies—meaning the next mayor could win with well under a majority of the vote.

Some argue that avoiding such a scenario would be a good reason for New York to use RCV in the general election, too. If it did, the argument goes, someone like Brad Lander might emerge and direct his voters to rank the most sympatico frontrunner. Campaigns like this, in which candidates instruct their supporters to rank other candidates, are crucial to ensuring that the winner commands majority (or near-majority) support.

Detractors counter that this assumes unrealistic cooperation. They might also point to deep disagreements within the Democratic elite. In response, the RCV supporter could cite the “vibes” interpretation of the Mamdani campaign. If elections are about vibes, not policy, why shouldn’t we expect an avalanche of RCV cross-endorsement?

The buzz around RCV is understandable but rooted in wishful thinking. Last month, writing for City Journal, I mentioned a paper that found 52.4 percent of modern RCV elections had ended in “majoritarian failure”—the winner receiving less than half of total ballots cast. Majoritarian failure happens either when many voters don’t rank choices or rank candidates eliminated early in the count.

This didn’t happen in winner Zohran Mamdani’s case, but it could have. After accounting for vote transfers, Mamdani won with about 53.1 percent of total ballots cast. A few more “exhausted” ballots, and he could have fallen below the 50 percent threshold. Now imagine if the race had not been a party primary but instead a single-shot RCV election that admitted all factions: left-wing Democrats, establishment Democrats, Curtis Sliwa’s wing of the Republican Party, and whatever “old line” Republicans still exist in New York City.

Other countries’ experiences are instructive. In Australia, which requires voters to rank all choices and invests heavily in voter education, the invalid-ballot rate hovers around 5 percent. This is because the voting task presumes high levels of educational attainment, facility with the English language, and acceptance of establishment politicians whom voters must rank for their ballot to be valid.

Debates about RCV’s benefits are effectively impossible to resolve because they require one to assess counterfactual scenarios. The best way forward may be to take seriously the Charter Commission’s proposed RCV qualifying round with a top-two general election. Whatever one thinks about RCV, the proposal is certain to generate a winner with a majority of votes cast in the election’s decisive round.

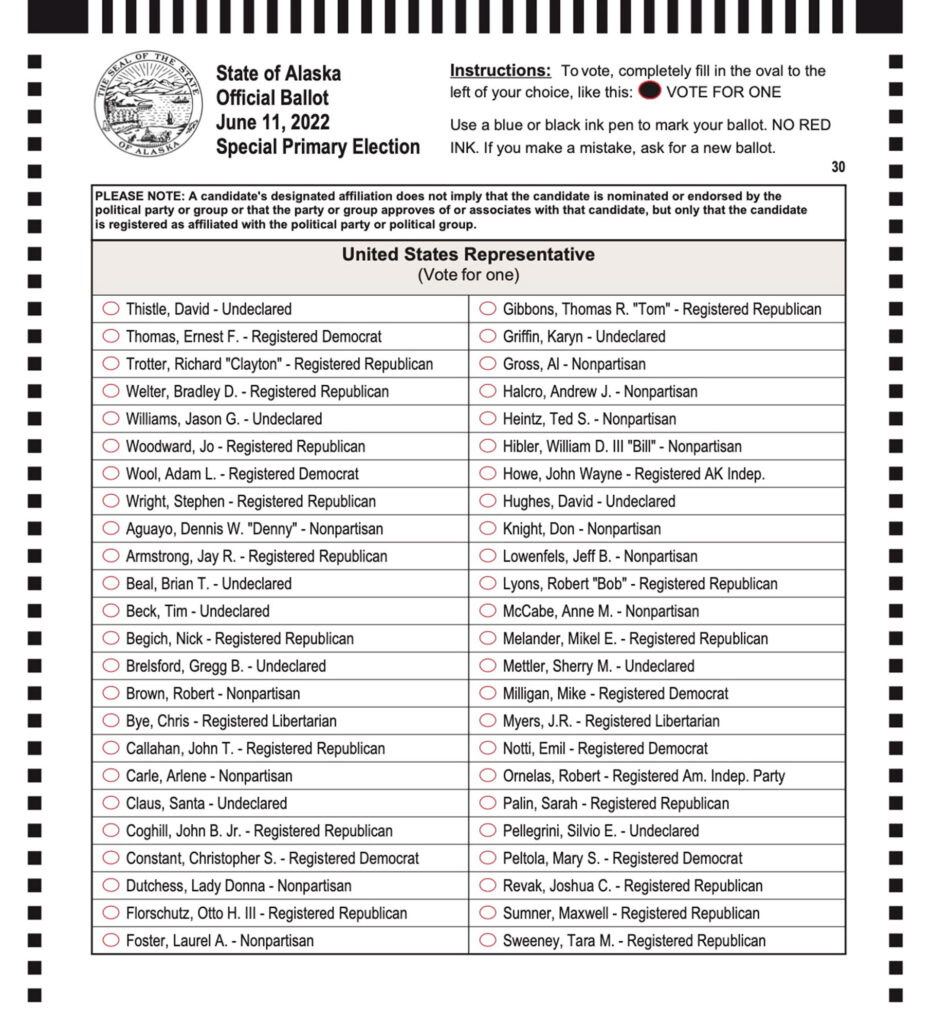

How should Gotham implement this system if it insists on adopting it? The Commission currently proposes printing “the party affiliation of candidates, if candidates are registered members of a political party” on both rounds’ ballots. This will create difficulties for voters.

To understand why, consider the sample ballot from Alaska’s 2022 “nonpartisan primary” pictured below. Alaska recently combined RCV with a “top-four” qualifying round. Under this system, the party label is almost useless for differentiating among candidates. Anyone can be a Democrat or Republican (or whatever else) simply by registering as such. New York City’s proposed “open primary” would modify this ballot by asking voters not just to choose one candidate (as in Alaska), but to rank several.

If the city’s goal is for two candidates to emerge from this process with broad support, it would be wise to let the parties decide which candidates get to use their labels. Voters could use that information to guide their rankings in the qualifying round. Activists may not like this advice, but most voters are not activists.

To ensure the parties remain a part of the process, New York could give nomination authority to conventions of district committees. It could also retain the essence of ballot fusion (so-called “fusion voting”) by listing each candidate on one line, with all his party endorsements.

This is no silver bullet—all kinds of “parties” could sprout up, as they’re doing now—but it’s better than junking a partisan vetting process altogether. It even might improve upon RCV in primaries, which currently removes party labels de facto. Finally, keeping parties in control could make it easier to get two clear frontrunners, enabling voters to factor control of government into their decisions.

More than a century ago, Lewis Carroll of Alice in Wonderland fame proposed a modified version of RCV to deal with elections that don’t produce majorities. He suggested holding runoffs until RCV could deliver what it promises: a winner who satisfies most voters. That approach enjoys a surprising amount of academic support; one pro-RCV scholar even based his preferred electoral system (a tournament-style election) on the logic of a choice between two options.

Ranked-choice voting has problems, but it also has many supporters. Done right, top-two elections could preserve that system—and lead to a better process overall.

Photo by Selcuk Acar/Anadolu via Getty Images

Source link