A preview from our upcoming Summer 2025 issue

Just after midnight on June 25, with the temperature finally down from a 100-degree high to the upper 80s, a hoarse and exhausted-looking Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani addressed a cheering crowd in Queens. Clad in a crisp white shirt under his dark suit and tie, the 33-year-old exulted: “My friends, we have done it. I will be your Democratic nominee for the mayor of New York City.” Indeed, Mamdani had done it—an upstart Democratic Socialists of America member with four years’ experience in office had pulled off a stunning victory in the city’s mayoral primary. From just 7 percent support in January polls, he surged to defeat former governor Andrew M. Cuomo by eight points. Cuomo, backed by tens of millions of dollars from business and real-estate interests and long leading in polls, had expected an easy path to the nomination. The result was the biggest political upset in New York in nearly 25 years—since Michael Bloomberg, running as a Republican after 9/11, edged out Democratic favorite Mark Green as voters chose a businessman over a party stalwart.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

It’s understandable that New Yorkers, and observers nationwide, see Mamdani’s victory as a sharp break in city politics. Going back more than three decades, voters have elected pragmatic leaders focused on public safety and economic growth. The exception, Bill de Blasio, benefited from the safety and prosperity created by his immediate predecessors. But the reality is less dramatic: Mamdani won not because voters embraced his self-described socialist agenda of government-run grocery stores and free buses, but because the alternatives were so weak. New Yorkers didn’t reject a centrist—they simply weren’t offered a credible one.

To understand the failure of Mamdani’s rival candidates to inspire, it’s worth looking back at the primary campaign, which began in January and played out across countless forums.

On a Tuesday evening in late May, veteran New York politico Scott Stringer sat in his Manhattan living room, peering into his laptop camera. He spoke confidently and capably about an issue affecting New Yorkers rich and poor: illegal noise. Whether from unpermitted construction or raucous park parties, Stringer argued, noise isn’t just a nuisance, it’s a health hazard—and he proposed enforcement solutions.

One problem: this Zoom forum, hosted by the NYC United Against Noise citizens group, drew fewer than a dozen attendees. The dismal turnout underscored the challenge that New York’s career state and local politicians faced this spring in a long, strange city election: voters barely noticed them. Stringer’s résumé was solid: lifelong Manhattanite, teenage community-board member, two decades in the state assembly, eight years as Manhattan borough president. Most notably, in 2013, he won a citywide election for comptroller against a formidable, well-funded opponent—former governor Eliot Spitzer.

By May, a month before early voting began, Stringer and more than half a dozen other career Democrats—from City Council Speaker Adrienne Adams to State Senator Zellnor Myrie—had been unable to generate interest with their consultant-tested, progressive-lite platforms: more child care for parents, more mental-health treatment for subway offenders, more subsidized housing. They had settled into roles as an often-indistinguishable supporting cast in a main-stage drama starring Andrew Cuomo and, increasingly, the rising Zohran Mamdani.

Opposites—Catholic vs. Muslim, native vs. immigrant, old vs. young, deadpan vs. eager—the two men sparred while sharing a core insight: voters wanted a dramatic savior. The June 24 choice between Cuomo and Mamdani came down to what kind of salvation Democratic voters believed the city needed.

Casual observers of New York politics might ask: What happened to the third guy? After all, the city already has a Democratic mayor—Eric Adams. A former police captain, Adams vaulted into office in 2021 as the law-and-order candidate. He won almost by default, despite a record of ethical lapses and limited management experience. At the time, New York was experiencing the sharpest public-safety decline in its history: following statewide criminal-justice reforms and Covid-19 disruptions, the local murder rate had jumped more than 50 percent since 2019. Adams prevailed because his Democratic rivals, in the post–George Floyd, defund-the-police climate, were reluctant to admit that public safety was voters’ top concern and that they wanted it addressed through stronger policing.

If you voted for Adams in the 2021 primary and general election and then tuned out for a few years, you might wonder why you couldn’t just back him again for a second term. After all, the mayor has a capable police commissioner, Jessica Tisch, and by late June 2025, the NYPD had reduced the city’s murder count to pre-2020 levels: 132 killings—just seven short of the record low for the same period in 2017. Subway crime, too, showed significant improvement: through late June, the city had recorded only two subway homicides, a near return to normal after five grim years that averaged eight or nine such killings annually.

Adams’s broader stewardship of the city also seems passable. He’s no austerity mayor, but spending hasn’t spiraled: the $121.2 billion budget has grown 16.5 percent over his first three years—roughly in line with high national inflation. The economy isn’t booming, but it’s not collapsing, either. Private-sector jobs have grown 17.8 percent since Adams took office, surpassing pre-Covid levels by nearly 4.6 percent.

True, the city is far from its pre-pandemic footing. Overall felonies remain nearly 31 percent above 2019 levels; underage gang activity has climbed; and quality-of-life issues—from open-air drug use to rampant shoplifting—though improved from the depths of 2020 and 2021, persist. Job growth also continues to lag the national pace. Yet for all its stumbles, New York is at least moving in the right direction.

In this primary season, Adams feared voters would judge him not by how the city looks today compared with four years ago, but by everything that happened in between—much of it fueled by his cronyism and erratic behavior. Tisch wasn’t his first police commissioner but his fourth; one predecessor, Edward Caban, resigned last year amid allegations of participating in a systemic shakedown of nightclubs, including over noise complaints. Adams treated the Biden-era border crisis—which brought hundreds of thousands of migrants to New York in 2022—as an opportunity to award billions in no-bid contracts to house tens of thousands in expensive hotels. He also signed a dubious deal with a campaign donor to distribute aid to migrants via prepaid debit cards.

The Adams circus appeared to reach its nadir in late 2024, with a federal indictment on corruption charges for allegedly trading government favors with Turkey in exchange for travel perks. In 2025, the incoming Trump administration dropped the charges, perhaps in return for political obeisance when it comes to local cooperation with new federal policies.

Even absent corruption, Adams’s governance has failed to inspire confidence. Despite his professed focus on public safety, the mayor let police ranks dwindle to modern record-lows, hundreds below the stated headcount of 35,051, forcing the NYPD to rely on mandatory overtime just to maintain coverage. This persistent shortfall means that Adams is always reacting to crises rather than preventing them. On quality-of-life issues, he flits from one initiative to the next—promising, for instance, to reduce the blight of sidewalk scaffolding one day, and then pivoting to a crackdown on prostitution along Roosevelt Avenue in Queens the next—without achieving much lasting progress.

All this helps explain why voters feel nearly as glum as they did four years ago. As a Citizens Budget Commission survey in early June found, just 34 percent of New Yorkers believe that the city’s quality of life is good, up slightly from 30 percent in 2023 but well below the 51 percent recorded in 2017. Similarly, only 42 percent feel confident in their neighborhood’s safety, an improvement from 37 percent in 2023 but still down from 50 percent in 2017. And just 22 percent feel safe on the subway at night, a figure unchanged over two years and less than half the 46 percent who felt safe in 2017.

So in April, the mayor—his approval rating at a historical low—announced that he wouldn’t compete in the Democratic primary but would instead run for reelection as an independent. He left voters searching for a new nominee with the same focus that they had once hoped he would bring: public safety, quality of life, and, increasingly, the cost of living.

By then, the Democratic primary’s eclectic field of soon-to-be also-rans had demonstrated its inability to engage the electorate on one, or both, of the issues voters cared about: public safety and affordability. At forum after forum, the candidates delivered slightly varied versions of the same tepid progressivism.

Reality scored an early, modest victory: the candidates—many of whom had championed “defund” rhetoric in 2020 and 2021—had to acknowledge that public concern about crime and quality of life was real. Stringer and his successor as comptroller, Brooklyn’s Brad Lander, were the first to adjust, seeking to position themselves as liberals with sanity. As Lander said at an April Vital City forum, “I think progressives, myself included, were slow to reckon with the elevation of crime and disorder that came through and out of the pandemic.” Stringer, meantime, tried to show how attuned he was to voter anxiety by describing how he worried about his young sons riding the subway—telling them to sit in the conductor’s car, just as he had done as a kid during the city’s high-crime years a generation and a half earlier. Zellnor Myrie recounted how, when he was a child in Brooklyn, he and his mother were robbed in an elevator.

But none of the candidates had the political skill to diagnose the obvious problems and offer obvious solutions. Part of the issue is the state’s pre-2020 loosening of criminal-justice laws. By restricting bail, the reforms have made it much harder to keep repeat offenders behind bars. By requiring prosecutors to turn over significantly more evidence (much of it minor) and to do so quickly, the laws have made it tougher to prosecute cases. And by eliminating adult consequences for serious teenage violence, they weakened deterrence against youth crime.

The answer, at least in part, is more policing and stronger criminal-justice laws—restoring the predictable deterrence that once applied even to low-level nuisance crimes. But this crop of mayoral candidates, shaped by years of courting progressive voters in low-turnout local races, couldn’t credibly align themselves with moderate voters’ mood and give them what they wanted.

Instead, the candidates offered half-measures and muddle. Mostly, they rallied around a safe issue: cheap child care. In 2013, Bill de Blasio won the mayoralty by promising universal pre-K for four-year-olds, a policy that proved popular across income levels. Twelve years later, every Democratic candidate offered a variation: Lander promised “2K,” or free kindergarten for two-year-olds; Stringer proposed a sliding-scale day-care plan, capped at 7 percent of family income; Adrienne Adams took credit for saving “3K,” free kindergarten for three-year-olds, from the mayor’s budget cuts. What they overlooked was that de Blasio pitched his plan to pragmatic voters in a different era—one less consumed by crime and quality-of-life concerns, and where progressives were still content with incremental change.

While most candidates looked to de Blasio, one—former hedge-fund manager Whitney Tilson—took his cues from Bloomberg. Tilson positioned himself as a centrist and diagnosed the city’s crime problems with rare clarity: “We went way too far in decriminalizing almost all but the serious crimes. And not surprisingly, we’ve seen a lot more of it.” But Tilson’s fate showed why Bloomberg ran as a Republican in 2001. In a Democratic primary, an outsider has little chance—no ideological bloc, no neighborhood base, no name recognition. Tilson started with nothing and, earning under 1 percent of the vote, finished about where he began.

Clinging to their disturb-no-one platforms, the Democratic rivals weren’t moderate enough for voters concerned about public safety—nor progressive enough for the city’s left wing. In the end, they cleared a path for a bolder upstart: Mamdani. He won his Queens state assembly seat in 2021 with DSA backing, one of the last New York politicians to benefit from the progressive wave that began in the mid-2010s and had seemingly crested around 2021.

Mamdani surged ahead of his Democratic rivals by running a vigorous campaign. He started early, last October, and steadily built a ground game, boosted by well-produced TikTok-style videos that radiated humor and authenticity. In one, he walked the streets interviewing vendors about rising prices, marveling that “chicken over rice now costs $10 or more. It’s time to make halal eight bucks again.” In another, he posed with a plastic fork and knife over a burrito on the subway: “Bon appétit from the Q train.” When establishment figures dismissed these as proof he wasn’t a serious candidate, they missed the point—he was trying to look unserious. He was making socialism fun. Behind the scenes, though, Mamdani was focused and disciplined, sticking to a tight schedule and a consistent message. In the final days of the race, as he closed in on Cuomo, he swapped his casual outfits for a suit.

Mamdani’s messaging worked, and so did the message. Unlike rivals pushing convoluted child-care subsidies or debating how many mental-health clinicians to deploy in the subway, he focused on simple proposals. His signature issue was something that no one else was talking about but that everyone could grasp: universal free buses. On child care, he went broader and less complicated than his opponents, promising “free child care for every New Yorker aged six weeks to five years,” with caregivers paid on par with public school teachers.

Mamdani similarly steamrolled through other politically fraught issues. He didn’t bother making a big show of contrition on changing his mind about his 2020-era support for the “defund the police” movement, as Lander did; instead, he just avoided talking about defunding the police. Rent too high? While most rivals, particularly Myrie, offered some version of expanded private development with subsidized units, Mamdani’s signature housing policy was blunt: freeze rents on the city’s roughly 1 million regulated apartments. He turned the abstract—if the city builds more housing, maybe my rent won’t rise as much—into the immediate: my rent will stay the same this year. Groceries too expensive? Mamdani blamed greedy store owners and proposed city-run grocery stores to cut out the middlemen. Still can’t afford food? Hike the minimum wage to $30—nearly double the current $16.50, already indexed to inflation. The struggling retail sector, he suggested, would find a way to absorb the cost.

How would he pay for it all—roughly $10 billion yearly in new government programs? While his rivals either dodged such questions or insisted that their proposals would somehow pay for themselves, Mamdani embraced what has traditionally been a liability, even for New York Democrats: he would ask the state to raise income taxes on the wealthy and on corporations. Problem apparently solved. Only one other primary candidate, Queens state senator Jessica Ramos, a former labor-union activist, endorsed tax hikes.

By March 2025, only two candidates, in a poll, garnered double-digit voter interest. One, at 16 percent, was Mamdani. The other, at 34 percent, had only just joined the race: Andrew Cuomo. As Adams was dropping out, Cuomo, after months of teasing, dropped in. New York’s governor from 2011 to 2021, Cuomo had cut his third term in office short just four years earlier, facing allegations of sexual harassment and following charges that he had covered up Covid-era deaths in nursing homes after requiring the facilities to accept patients who tested positive.

Like Mamdani, Cuomo ran on a straightforward message: “Our city is in crisis,” he warned, mostly one of crime and quality of life. “Nothing works without public safety,” he said two weeks before the primary. “People feel the city’s out of control.” His solutions were just as direct. Reporters snarked that Cuomo cribbed his policies from ChatGPT, but simplicity was the point. He’d put more cops on the streets and subways, for example, raising the level to nearly 39,000, close to early 1990s highs. (He was unclear about how he would pay for this: savings would apparently come from reduced overtime.) He’d expand involuntary treatment for the seriously mentally ill. And he wouldn’t raise taxes. Cuomo derided Mamdani’s agenda as “Everything free . . . tax the rich.” He warned against “class warfare,” arguing that wealthy residents would flee. “We lost 500,000 people since Covid. . . . People will say, I’m going to Florida, I’m going to Texas … especially since the quality of life has deteriorated. Why would I pay to live here when I’m not getting the benefit of living here?” All quite reasonable, and backed by evidence of a recent erosion of the state’s tax base.

But because Cuomo entered the race so late, Mamdani had coasted for months with no challenge to his signature tax-raising policies, which would mean the highest combined state and city corporate tax rate in the nation, by far, as well as a near 50 percent hike in the city’s personal income-tax rate on top earners, even as New York has struggled with a slow economic recovery from pandemic lockdowns.

Cuomo, as a centrist, was also deeply compromised. Moderate voters had to suspend disbelief to trust he would govern effectively, given his own political past. He was Schrödinger’s candidate: two opposites at once. In his first two terms, he governed pragmatically, reining in spending after the 2008 financial crisis. But as progressivism surged around 2016, he veered left. His tough-on-crime mayoral pitch clashed with his record: he signed the lenient criminal-justice laws that contributed to the post-2020 crime spike. He closed inpatient psychiatric wards in favor of loosely structured community care, putting more mentally ill homeless people on the streets. He warned against taxing the wealthy—yet had done exactly that in 2021, during the Covid exodus, despite federal stimulus funds already covering state and city deficits.

On one issue in particular, Cuomo’s contorted mayoral stance mirrored his own contradictions. The next mayor will inherit the long-delayed de Blasio-era plan to close Rikers Island and replace it with four smaller borough-based jails, each still in early construction. But these new facilities will hold less than half of Rikers’ current population. Making the plan work would require slashing inmate numbers to levels unseen in modern history, risking a repeat of the 2020 crime surge.

Cuomo, who understands infrastructure—he built a replacement for the Tappan Zee Bridge and rebuilt LaGuardia Airport as governor—knew that the Rikers plan is unworkable. Yet at an April forum of Al Sharpton’s National Action Network, he called Rikers “inhumane” and pledged to close it. In a New York Times interview, he said that he would solve the problem by moving the seriously mentally ill from Rikers to supportive and community-based housing. But Rikers isn’t a housing facility; it’s a jail, for people charged with serious crimes.

Cuomo expected to get away with shape-shifting on his signature issue when his Democratic rivals couldn’t. In a June debate, when Stringer pressed him on bail reform, Cuomo dodged by raising a tenuous point about city contracts involving Lander’s wife. It wasn’t a stumble; it was the best of two bad options: either re-alienate the Left by repudiating his own bail-reform law or re-alienate the middle by defending it. Cuomo had moved on because it was his only palatable choice—and he hoped voters would, too.

Cuomo bet that New Yorkers would accept his protean reinvention partly out of desperation: no other experienced candidate seemed more credible as a moderate. He also counted on voters’ faith in his sheer force of will. As governor, he had gotten big things done, from major infrastructure projects to the legalization of gay marriage. That some may have been the wrong things seemed beside the point. As mayor, he would surely govern from the center—because he had run as a centrist and would need to fend off future reelection challenges from the middle.

Or would he? As Mamdani closed the polling gap in May and June, Cuomo shifted left. In response to Mamdani’s call for a $30 minimum wage, Cuomo proposed $20. Early in his gubernatorial tenure, he had raised the public-sector retirement age for non-uniformed workers to 63; now, as a mayoral candidate, he proposed reversing that reform. He also secured a key endorsement from the low-polling Jessica Ramos, a former labor activist who might help deliver Hispanic and union-aligned votes—adding to his growing list of labor backers.

Cuomo seemed to sense, though, that his fragile center wouldn’t hold through June 24. And it didn’t. As early voting began on June 14, he collapsed in slow motion, eventually losing to Mamdani in a landslide—44 percent to 36 percent—as the other rivals faded into the background. On Election Night, Cuomo seemed almost relieved. “Tonight was not our night,” he told supporters. “Tonight was Assemblyman Zohran Mamdani’s night.”

It’s no mystery why moderate voters stayed home. The oppressive heat played a role, disproportionately affecting older voters, who tend to worry more about the city sliding into a spiral of crime and population loss without steady leadership. But the deeper reason was demoralization: moderates had no candidate. And it’s equally clear why progressive voters turned out in force—they had their man.

New Yorkers will get one final chance to decide whether Mamdani’s victory is just for the summer and fall—or for the next four years. For the first time since the Bloomberg era, the mayoral race doesn’t effectively end with the Democratic primary. In November, voters will be able to pick the Republican nominee, Curtis Sliwa, founder of the Guardian Angels, who ran unsuccessfully against Adams in 2021. Cuomo, too, will remain on the ballot on a third-party line, though it’s unclear if he will campaign.

And they’ll have another option: Mayor Adams himself, running on two third-party lines—“Safe & Affordable” and “End Anti-Semitism.” Hours after Mamdani’s victory, Adams officially launched his campaign, calling his rival a “snake-oil salesman.” Adams’s pitch, as he previewed to the New York Post that afternoon, will be just as pointed as Mamdani’s: he’s sorry for the mistakes of his first term, including his botched deputy mayor and commissioner appointments. But he’ll ask voters what sounds better: Four more years of steady, if imperfect, progress on crime and economic growth, or an untested ideologue with a radical tax plan and a record of supporting police defunding?

The more centrist general electorate—still concerned about crime, if less intensely than in 2021, and only beginning to grasp the potential economic and fiscal risks of a Mamdani administration—will have to choose from among deeply flawed candidates. For New Yorkers, it’s the devils you know versus the devil you’re just getting to know.

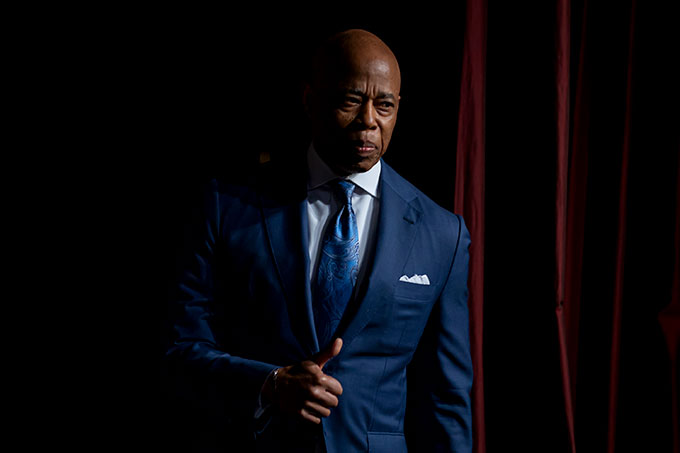

Top Photo: Democratic Socialist Zohran Mamdani, a state assemblyman, ran a primary campaign stressing affordability, while making unaffordable new spending commitments that included free childcare—and won decisively. (Yuki Iwamura/AP Photo)

Source link