While speaking at the annual NATO summit on Wednesday, Trump quietly acknowledged that his claim that the United States had “obliterated” Iran’s nuclear program was premature.

After the United States Air Force’s Northrop B-2 Spirit bombers struck Iran’s Fordow nuclear facility with the 30,000-pound GBU-57/B Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP) bunker buster bomb, President Donald Trump said the strikes “completely and totally obliterated” the sites.

Similarly, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth also told reporters on Sunday that Iran’s nuclear capabilities had been “obliterated” during “Operation Midnight Hammer,” sortie that saw the long-range bombers fly from Whiteman Air Force Base (AFB), Missouri, and back. That mission marked the first time the MOP had been used in a combat operation—apparently with total success.

Iran’s Nuclear Program Has Been Set Back—but Not “Obliterated”

But while “obliterated” has become the go-to word of the week in describing the state of Iran’s nuclear facilities by some in the administration, another word is also being repeatedly used by many in the intelligence community: “intact.” There is growing speculation that, despite the highly touted capabilities of the GBU-57/B MOP bunker buster, it did not succeed in busting Iran’s bunkers—at least not at Fordow, where the nuclear facility is built under a literal mountain and fortified with many tons of concrete.

To be clear, the strikes certainly damaged Iran’s nuclear program. But the damage has likely been overstated. The current speculation within the US intelligence community (IC) is that the strikes have set back Iran’s nuclear program by months rather than years, according to leaked Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) assessment documents obtained by CNN. That is a far cry from “obliterated.”

The White House has since responded to the media reports that question the IC findings, alleging that the leaked documents were part of an attempt to discredit the administration and even the “fighter pilots” involved in the mission—although the operation was carried out by bombers supported by hundreds of other aircraft.

“Everyone knows what happens when you drop fourteen 30,000-pound bombs perfectly on their targets: total obliteration,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt told CNN in a statement.

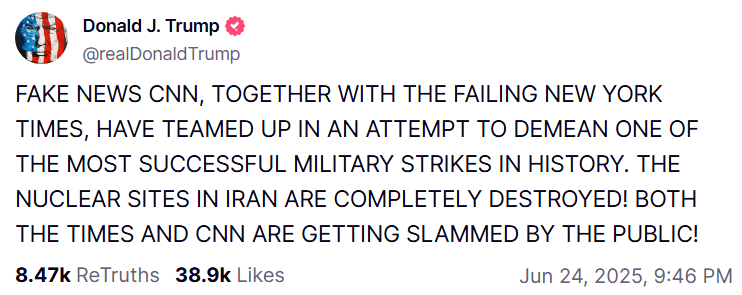

President Trump also doubled down on his claims, writing on Truth Social, “ONE OF THE MOST SUCCESSFUL MILITARY STRIKES IN HISTORY. THE NUCLEAR SITES IN IRAN ARE COMPLETELY DESTROYED!”

More quietly, while speaking at the NATO Summit in The Hague on Wednesday, Trump acknowledged the intelligence was “inconclusive,” a signal that his earlier claims overstated the damage.

“The original word that I used—I guess it got us in trouble, because it’s a strong word—it was ‘obliteration.’ And you’ll see that—and it’s going to come out. Israel is doing a report on it, I understand. And I was told that they said it was total obliteration,” the president added.

Iran Used Special Concrete at Its Fordow Facility

The exact state of the Fordow facility is currently unknown, as Western analysts must rely on satellite images to assess the damage. Yet, experts believe it could be partially or even entirely intact, not just because it is built into a mountain but because of the aforementioned concrete.

This is far from the run-of-the-mill variety of concrete used in the construction of roads, bridges, and buildings. Iran is believed to be using “Ultra High Performance Concrete,” which may have a compressive strength 10 times that of traditional concrete—making it far more resilient to external shocks.

The term Ultra High Performance Concrete (UHPC) was first coined in 1994, although the United States Army Corps first developed it in the 1980s for projects that required greater strength, such as barracks and command centers. It became commercially available in 2000 and is now widely employed in infrastructure projects.

By now, the recipe for UHPC is well-known, and many countries use it. As Popular Mechanics reported, the “greater strength is achieved” by adding steel and other fibers into the mix, essentially transforming normally brittle concrete into a “composite material” where the addition of fibers helps prevent cracking. UHPC can absorb far greater kinetic energy.

The Bombs-Versus-Concrete Arms Race Continues

Since the First World War, when the German Army fortified its bunkers with concrete, there has been an arms race in developing ordnance capable of destroying or busting the bunkers. However, it wasn’t until World War II that the Germans also developed the Röchling shells, which were designed to penetrate concrete-reinforced bunkers.

The British followed with their 22,000-pound Grand Slam, the largest and most powerful conventional aerial bomb used in the war. Known as an “Earthquake” bomb, it featured a steel casing that allowed it to penetrate a hardened surface before detonating.

The technology further improved during the Cold War, but it was in the lead-up to the 1991 Gulf War that the US learned that Iraq had underground bunkers reinforced with concrete. It was quickly determined that the existing 2,000-pound bunker busters would not be effective against such facilities, and efforts were put in high gear to develop more capable ordnance. In less than a month, the Air Force Research Laboratory Munitions Directorate at Eglin Air Force Base (AFB), Florida, delivered improved bunker busters that the General Dynamics F-111 Aardvark later dropped on the Iraqi bunkers.

Since 2012, the US Air Force has been studying how to better penetrate such hardened facilities. This eventually led to the development of the 30,000-pound MOP, which can only be carried by the B-2 Spirit—although it will likely also be able to be carried by its eventual replacement, the Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider.

There is already speculation that the MOP simply isn’t up to the job at hand, and something bigger and more powerful will be required. The US Air Force does not have aircraft yet in service to deliver such a weapon. Nor is the B-21 likely to be capable of carrying a larger bunker buster bomb.

That’s just part of the concern. The other part is the other side of the arms race.

As Popular Mechanics further reported, China has been testing “Functionally Graded Cementitious Composite” (FGCC), a form of layered UHPC with varying properties. The largest conventional ordnance in service today may not be able to penetrate such materials, nor will the problem be solved by further increasing the size of the current bombs.

What might the next step be? Perhaps the United States or other world powers could use hypersonic missiles, which utilize speed and kinetic energy rather than a chemical explosion. It may take such a weapon to bust the next generation of bunkers.

Ever since the massive walls that once defended Europe’s cities for more than a millennium were defeated by the introduction of gunpowder and cannons, an arms race between fortifications and the weapons to destroy them has been ongoing. Right now, it seems the fortifications are winning—at least until a new type of weapon is introduced.

About the Author: Peter Suciu

Peter Suciu has contributed over 3,200 published pieces to more than four dozen magazines and websites over a thirty-year career in journalism. He regularly writes about military hardware, firearms history, cybersecurity, politics, and international affairs. Peter is also a Contributing Writer for Forbes and Clearance Jobs. He is based in Michigan. You can follow him on Twitter: @PeterSuciu. You can email the author: [email protected].

Image: Shutterstock / Rokas Tenys.