Within a few seconds of entering “Willem de Kooning: Endless Painting” at Gagosian in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood, you will see sparkling examples of grand and intimate works spanning a lifetime. These are the works of Willem de Kooning, one of the greatest twentieth-century painters, on par with such artists as Matisse, Picasso, and Pollock.

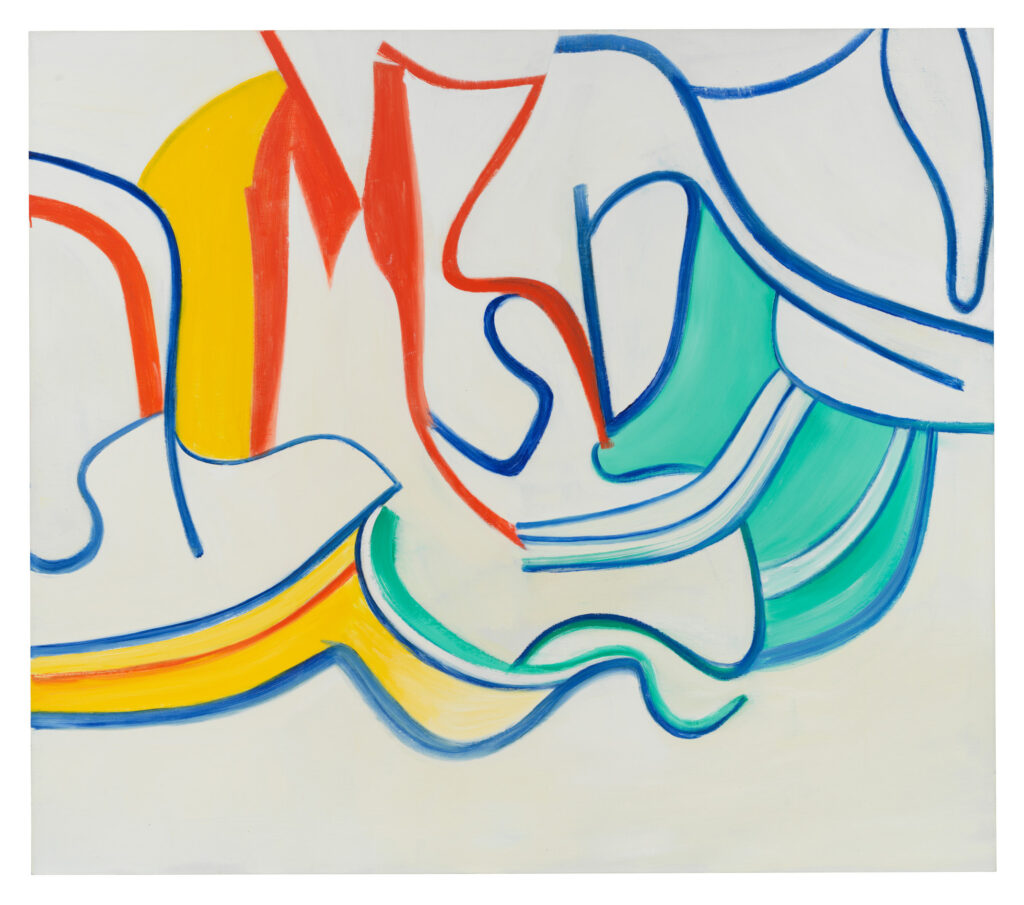

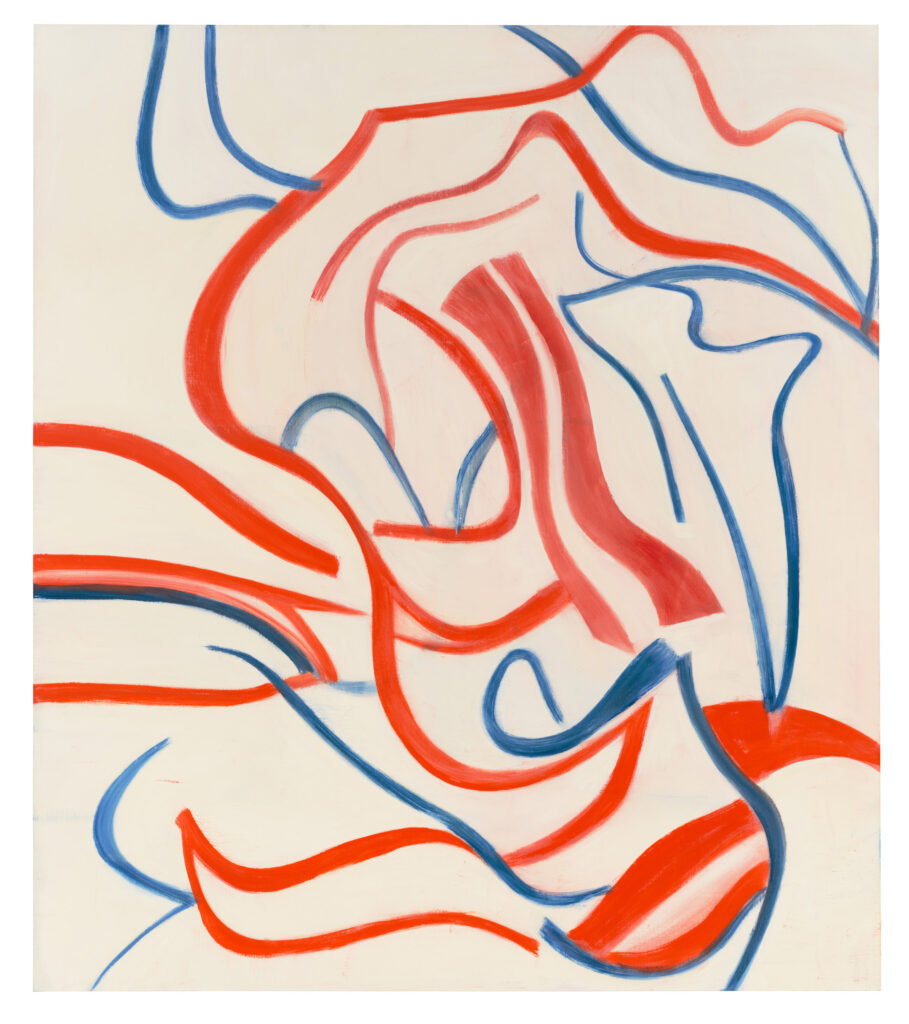

Representing De Kooning’s huge oeuvre—from the 1940s, when his primary audience was his group of downtown friends, to the 1980s—are twenty-two paintings, ten of them from the late 1970s and the 1980s, as well as two bronze sculptures. Facing you first are three monumental and lyrical late abstract works. Beyond these an early de Kooning is put next to a late one, an overtly sexual figure next to an abstract pastoral; the works are not chronologically organized. The curation juxtaposes paintings from all periods and styles, showing how these works maintain the artist’s characteristic space, line, subject matter, and richness of meaning while remaining always visually exploratory in essence.

The show is timely. Some artists today are perceiving a new depth and relevance in de Kooning’s oeuvre, including the unsurpassable richness of his drawing (in paint) as well the coexistence of complex abstract and figurative structures in his lines and colors. While this was clear seventy-five years ago, the art world largely has looked elsewhere in the intervening years, seeking in art primarily literary or political storytelling. Some artists have not forgotten, or have managed to discover, what de Kooning really did, though many never learned. He is a revelation today, especially thanks to this exhibition.

De Kooning was born in Rotterdam in 1904. As a youth he studied for eight years at a conservative academy of art, where the curriculum included De Stijl due to the Dutch art movement’s practical application. De Kooning said that he and his friends then didn’t know there was art in America, but they looked to it as a land of opportunity.

He came to New York as a stowaway at the age of twenty-two. And though he was a fixture of the New York avant-garde scene by the late 1930s and was always known as an American artist, he only became a U.S. citizen in 1962, long after he became famous.

Great painting requires mastery of its fundamentals: line, color, space. Willem de Kooning certainly met these requirements. It is worth comparing the works on view at Gagosian to the Old Masters that inspired him. The flowing structure of figures in de Kooning’s Montauk II (1969) holds up swimmingly to the swooning and swirling women in Rubens’s The Arrival of Marie de Medici at Marseille (1625). Compare the sinewy expressiveness of de Kooning’s line in . . . Whose Name Was Writ in Water (1975) with that of the undeniable Rembrandt. Or note the challenging, glowing crystallization of color and space in de Kooning’s Milkmaid (Untitled X) (1984) and that in the modern master Piet Mondrian’s New York City (1942).

For some, de Kooning’s pictures are hard to look at and their depth difficult to understand. They can be seen as an excruciating dance of structure, always reconsidering itself. Cyclical questioning and answering (is the painting good now? is this what I want?) is characteristic of all the periods in his painting.

After the culminating triumph of his abstract period, the masterpiece Excavation (1950), which is not in this show,de Kooning turned sharply to Renaissance and Baroque inspiration for about five years. He said of his famous “Women” series, “It had to do with the female painted through all the ages, all those idols. And maybe I was stuck to a certain extent; I couldn’t go on.”

There was a great hubbub at the unveiling of de Kooning’s “Women” in the early 1950s, and they remain, for some, an issue. In a time of intense widespread dedication to the new Abstract Expressionist style, his return from abstraction to figuration started with Woman 1 (1950), not in this show. “Some painters, including myself . . . do not want to conform. They only want to be inspired,” he said. There are two strong examples of this series at Gagosian: Woman (Green) (1953–55) and Woman as Landscape (1954–55). The artist wrote of this series, “It’s rather like the Mesopotamian idols . . . . They always stand up straight looking to the sky with this smile, like they were just astonished about the forces of nature . . . not about problems they had with one another.”

One of the reasons artists draw from the live model is because of the difficulty and subtlety of drawing the curves of the female body. The curves, even when disembodied, imply space. It’s the best way to learn to draw, whatever way you invent to carry it off.

After the “Women” series, de Kooning painted cityscapes, landscapes, and more women. By the mid-1950s he was famous, and many people wanted his time as well as his paintings. Until then he had little money. In 1963 he moved from downtown Manhattan to the town of Springs in East Hampton. There, he designed and built a new studio and continued his work in peaceful, rural surroundings, a bicycle ride from the bays and the sea.

In the late 1980s Alzheimer’s gradually drew de Kooning’s painting practice to a close (he died in 1997). Gagosian’s exhibition includes paintings as late as 1986. There has been doubt about the quality of his late paintings, but Alzheimer’s (or, simply, senility) does not diminish you all at once, and you do not need all your faculties to paint. A genius in one human capability does not require a genius in all. His late work is not bothered by the mass of experiences that guided his earlier work. By then, he had rehearsed many times the solutions to painting problems; he is freer in these works. The slimmed-down style invites comparison to the simple-looking but multi-dimensional space in a late Mondrian work. It also recalls de Kooning’s pre–Abstract Expressionist style, as in Bill-Lee’s Delight (1946).

Willem de Kooning was a Dutchman who flew the coop of the Old World for the open opportunities of the New. Yet he carried the Old World with him, remembering what was important to him from the experience and achievement of the past. After a while he considered himself an American painter, more specifically a New Yorker. He loved New York. His paintings, like a life in the city, flit from one moment of perception and opportunity to the next, illuminating his subject and his thoughts with a “slipping glimpse,” as he put it, but immediately flying on to the next set of perceptions, continuing his search.

As Clement Greenberg wrote in 1953, “Obviously this is highly ambitious art, and indeed de Kooning’s ambition is perhaps the largest, or at least the most profoundly sophisticated, ever to be seen in a painter domiciled in this country.” De Kooning’s painting was a record of his life: the mind active in the painting at one moment and reacting to it in the next. Uninhibited brushstrokes, intensely observed, recollect parts of art from the past, things he had seen out on the street, out the car window, views near the ocean, detached letters and symbols, views of the human body and its parts. At some point of working in a painting, the results reached a moment of satisfaction, or perhaps futility. He was asked, in an interview how he knew a painting was finished. “I just stop,” he said. As the title of the exhibition says, this is “endless painting.”