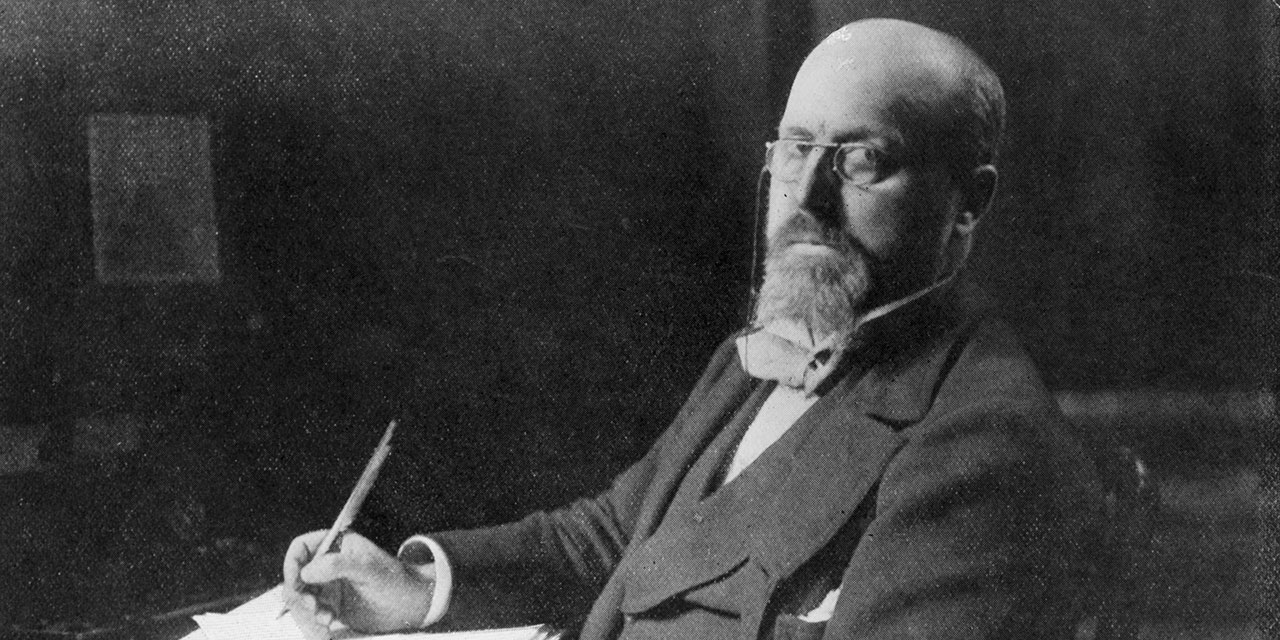

On Writers and Writing: Essays by Henry James, edited by Michael Gorra (New York Review Books, 408 pp., $24.95)

The criticism of Henry James (1843–1916) is replete with imperiousness. We can hear this in his not altogether facetious response to Thomas Hardy’s Far from the Madding Crowd (1874). Deploring the undue attention Hardy pays to Gabriel Oak’s watch, James urges that if novels are to keep their esteem among readers, they must “lighten their baggage . . . and do battle in a more scientific equipment.” As to what constitutes this equipment, he is blithely dictatorial. “No tale should exceed fifty pages; no novel two hundred . . . plots should have but such and such ramifications . . . no person should utter more than a certain number of words . . . and no description of an inanimate object should consist of more than a fixed number of lines.” James admits that for the rehabilitation of bungling novelists such “oppressive legislation” might only need to be imposed as a “temporary straitjacket.” Still, “The use of the strait-jacket would have cut down Mr. Hardy’s novel to half its actual length. . . . Everything human in the book strikes us as factitious and insubstantial; the only thing we believe in are the sheep and the dogs.”

Reading this peremptory hatchet job, we can see why the dying writer should have been preoccupied with the emperor Napoleon. James had the emperor’s zeal for rule, even though the land he sought to rule was one to which most of his American compatriots could not have been more indifferent. After all, many of them were businessmen, or, as Matthew Arnold liked to call them, “Philistines,” men for whom culture meant nothing. For James, culture meant everything. When Arnold’s compatriots charged him with being insufficiently practical, James came to his fellow critic’s defense with what must have struck him as an irrefutable rejoinder: “It is quite enough to the point to be one of the two or three best prose writers of one’s day.” If one wished to advance the goods of culture, James insisted, there was “nothing more practical” than speaking “in the tone and with the spirit . . . of culture.”

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

While it is true that James’ fiction battens on the labyrinth of consciousness, his criticism delights in brass tacks. In this regard, if in no other, he had something in common with the age’s businessmen. On the historian of the English Reformation, James Anthony Froude, for instance, he says:

Mr. Froude’s volume opens with a lecture on the science of history, a very loose piece of writing for one who has made the study of history the business of his life. “One lesson, and one only,” says Mr. Froude, “history may be said to repeat with distinctness, that the world is built somehow on moral foundations; that in the long run it is well with the good; in the long run it is ill with the wicked.” If this is all that history teaches, we had better cease to trouble ourselves about it.

About another eminent Victorian, Charles Kingsley, famous for extolling “muscular Christianity,” James is equally foursquare.

Mr. Kingsley was the apostle of English pluck, English arms and legs, and the English sporting and fighting temperament generally, and he has given some admirable illustrations of these fine things; but we imagine that the accepted Kingsleyan type of manhood has lately come to be regarded as having a certain inadequacy. The average well-developed young Englishman of the present moment would be likely to feel that it offered a meagre allowance for the stowage of the cerebral parts.

These pieces appeared in The Nation in the 1860s and 1870s. Yet in an introduction to The Tempest published as late as 1907, one can see James the critic’s severely practical interest in the art of romance, even in prose steeped in the most elaborate analogy.

The man everywhere, in Shakespeare’s work, is so effectually locked up and imprisoned in the artist that we but hover at the base of thick walls for a sense of him; while, in addition, the artist is so steeped in the abysmal objectivity of his characters and situations that the great billows of the medium itself play with him, to our vision, very much as, over a ship’s side, in certain waters, we catch, through transparent tides, the flash of strange sea-creatures. What we are present at in this fashion is a series of incalculable plunges . . . I mean, after the great primary plunge, made once for all, of the man into the artist: the successive plunges of the artist himself into Romeo and into Juliet, into Shylock, Hamlet, Macbeth, Coriolanus, Cleopatra, Antony, Lear, Othello, Falstaff, Hotspur; immersions during which, though he always ultimately finds his feet, the very violence of the movements involved troubles and distracts our sight. In The Tempest, by the supreme felicity I speak of, is no violence; he sinks as deep as we like, but what he sinks into, beyond all else, is the lucid stillness of his style.

In On Writers and Writing: Essays by Henry James, a newly published collection edited by the crack James critic Michael Gorra, style is a constant theme. Speaking of George Sand, James says: “For five-and-forty years of her literary career she had something to say about most things in the universe; but the thing about which she had least to say was the writer’s, the inventor’s, the romancer’s art. She possessed it by the gift of God, but she seems never to have felt the temptation to examine the pulse of the machine.”

For James, examination of “the pulse of the machine” in the work of English, American, French, and Russian writers was of the essence of good criticism. In Zola’s Nana (1880), for example, an unflinching foray into the life of prostitution—not a subject one would have thought James would have found tolerable—he actually misses “the machinery of reality.” Why? “The figure of the brutal fille, without a conscience or a soul, with nothing but devouring appetites . . . has become the stalest of the stock properties of French fiction, and M. Zola’s treatment has here imparted no touch of superior verity.” If this exemplifies James’ idea of good criticism, we can see what he regarded as bad criticism in what he styled the “vulgarity” and “stupidity” of the “off-hand review” and “our wonderful system of publicity,” both of which could only attest to “the failure of distinction, the failure of style, the failure of knowledge, the failure of thought.”

The unique distinction of the novel for James, Gorra argues, is that it gives author and readers alike the freedom to enter into the real adventure of life, which is often misperceived. In “The Lesson of Balzac” (1905), James reminds his readers that “there is no such thing in the world as an adventure pure and simple; there is only mine and yours, and his and hers—it being the greatest adventure of all . . . just to be you or I, just to be he or she.” Flannery O’Connor certainly confirmed this adventure when she told a friend how “when I read James I feel something is happening to me, in slow motion but happening nevertheless.” Gorra nicely recognizes how instrumental this understanding of the novel’s communal charge was to the form’s future. “Balzac respected ‘the liberty of the subject,’ but he could hardly have imagined what James and his successors would make of that freedom, of their pulse-by-pulse evocation of everyday life, their dive into the flux and flow of consciousness.” The James novel that best captured this “flux and flow” was The Portrait of a Lady (1881), about which Gorra has written an exceptional study, seeing it as the culmination of the novelist’s early and middle and the harbinger of his late career.

Unlike Colm Tóibín, whose writings on James often leave one feeling that the only thing worse than identity politics is identity criticism, Gorra is a close reader whose understanding of the unity of James’ work arises naturally from his respect for biography and history, as well as form and style. In choosing his collection, he has done honorable service not only to the study of James but to our battered culture. He certainly reminds us of Henry James’s great good belief in the nobility of the novel. Indeed, in choosing to include the late essay, “The Future of the Novel” (1899), Gorra shows how deeply appreciative James is of what an antidote the novel and criticism of the novel offer in face of what our “rank civilization,” as he called it in The Bostonians (1886), has up its sleeve when it comes to our vulnerable human dignity. “Man rejoices in an incomparable faculty for . . . mutilating and disfiguring any plaything that has helped to create for him the illusion of leisure,” the critic in James writes.

Nevertheless, so long as life retains the power of projecting itself upon his imagination, he will find the novel work off the impression better than anything he knows. Anything better for the purpose has assuredly yet to be discovered. He will give it up only when life itself too thoroughly disagrees with him. Even then, indeed, may fiction not find a second wind, or a fiftieth, in the very portrayal of that collapse? Till the world is an unpeopled void there will be an image in the mirror. What need more immediately concern us, therefore, is the care of seeing that the image shall continue various and vivid.

In this rallying for an imperial cause always in peril, one can see a nod to Prospero, about the meaning of whose “rough magic,” on the brink of the cataclysm of the Great War, James wrote something that could stand as a tribute to his own magic, especially if we stop to consider how unexpected it was for America or his adopted England to produce so genuinely cosmopolitan a talent:

The face beyond any other . . . I seem to see in The Tempest turn to us is the side on which it so superlatively speaks of that endowment for Expression, expression as a primary force, a consuming, an independent passion, which was the greatest ever laid upon man. It is for Shakespeare’s power of constitutive speech quite as if he had swum into our ken from another planet, gathering it up there, in its wealth, as something antecedent . . . something that was to make of our poor world a great flat table for receiving the glitter and clink of outpoured treasure.

In Michael Gorra’s collection, the “outpoured treasure” is altogether dazzling, though imperiousness is not the only note struck by the critic in James. He can also show a winning humility, as when, speaking of an erotic novel’s effect upon his sensibilities, he admits that, far from emboldening him to take advantage of “emancipations,” it only leaves him with what he calls a “yearning” for “dear old Jane Austen.”

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Source link