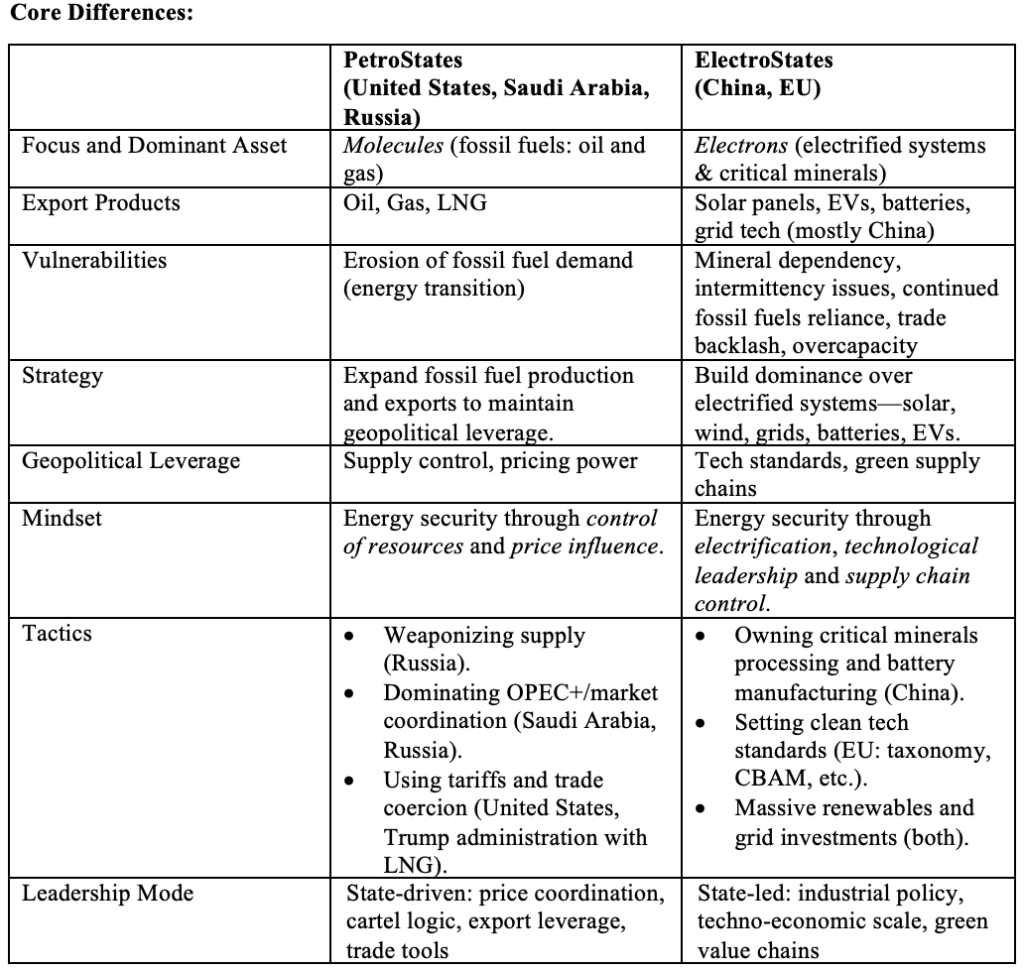

Fossil fuels and clean energy are reshaping global power as PetroStates and ElectroStates compete to define the future of energy and influence.

The global energy order is entering a period of profound realignment. Three fossil-fuel giants (or PetroStates)—the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Russia—are consolidating influence, even as China, the emerging ElectroState, pursues a divergent technological trajectory more aligned with Europe’s green ambitions. The result may be a volatile, asymmetric contest for energy dominance, pitting hydrocarbons against electrons and defining the energy and geopolitical landscape of the next decade.

What Has Changed?

Over the past decade, the United States has emerged as the world’s largest producer of oil and natural gas and the largest liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporter. While the Biden administration sought to align exports with climate goals, the new Trump administration has pivoted to maximizing fossil fuel use and enhancing America’s role as a global supplier of hydrocarbons. Since taking office in January 2025, the administration has announced a decisive fossil fuel shift—extending beyond the familiar rhetoric of “energy dominance.”

The United States increasingly resembles the other two major Petrostates—Saudi Arabia and Russia. A strategic alignment among the three, once unthinkable, can no longer be dismissed. Yet any such alliance would face a major counterweight: China, steadfast in reducing fossil fuel dependence and leading in many power-related technologies.

PetroStates: Using Fossil Fuels to Dominate Energy Relationships

All three countries want to leverage fossil fuel exports—oil and natural gas—to influence global energy and geopolitical relationships. Russia has done so for the past twenty years, most recently weaponizing gas during its war with Ukraine, while President Trump has used tariffs to pressure countries into buying U.S. LNG.

On the other hand, Saudi Arabia has historically leveraged its position as the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries’ (OPEC) de facto leader to manage crude production, influence oil prices, and cultivate deep ties with key importers in Asia and beyond. More recently, it has begun building an LNG portfolio—a strategic move to diversify exports and preserve its status as a major energy power in an evolving global market.

A New OPEC?

Together, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the United States accounted for approximately thirty-one million barrels per day (mb/d) of crude oil production in 2024—surpassing the output of all OPEC members and making up roughly one-third of global oil output. Since Riyadh and Moscow forged a strategic partnership that created OPEC+ in 2016, the group’s direction has been largely steered by these two heavyweights, whose production far exceeds that of OPEC+’s smaller members. Despite Russia’s frequent quota violations and the painful 2020 price war, the Russo-Saudi axis has remained central to OPEC+ decision-making.

These three countries may appear to have little in common—especially given the threat that U.S. shale oil posed to Saudi dominance—but they now share a commitment to energy dominance, particularly through fossil fuels, with none supporting a transition away from hydrocarbons. The recent Conference of the Parties 29 (COP) summit in Baku highlighted Saudi Arabia’s efforts to undermine COP28’s previous commitment to phase out fossil fuels, and the new Trump administration has already announced that the United States will withdraw again from the Paris Agreement. Meanwhile, Russia, though formally participating in international climate frameworks, continues to resist aggressive emissions targets in order to safeguard its fossil-fuel revenues, effectively aligning with other oil-reliant states seeking to weaken or delay global phase-out efforts.

Yet, forging a lasting alliance would be far from straightforward. A critical fault line lies in their divergent approaches to oil prices. President Trump has consistently advocated for low oil prices—around $50 a barrel (bbl)—arguing that cheaper energy fuels economic growth and benefits American consumers. In contrast, Saudi Arabia and Russia favor higher price levels to sustain their fiscal budgets. For Saudi Arabia, a high breakeven oil price contributes to national financial stability, while Russia, likewise heavily dependent on oil revenues, views higher prices as vital to funding its budget and broader geopolitical ambitions. However, tensions have recently resurfaced within OPEC+. Since April 2025, Saudi Arabia has quietly begun punishing quota violators by opening the taps and offering lower-priced crude to key buyers, while resorting to higher debt to balance its budget. Russia, though clearly unhappy—given its urgent need for wartime revenues—has followed Saudi Arabia’s lead, unwilling to jeopardize the alliance.

Another difference lies in the countries’ oil ecosystems: National Oil Companies (NOCs) in Saudi Arabia and Russia follow their governments’ strategies, whereas there is no clear leadership in the United States due to its network of private producers.

Yet all three powers recognize the danger of excessively high oil prices: higher inflation, the erosion of long-term global demand, and the acceleration of the shift to alternatives. Whether the current market softness—and its potential to dampen U.S. oil shale production—will prompt a recalibration of Washington’s preferred price band remains to be seen.

The Fate of Gas and LNG: GasPec?

Meanwhile, the idea of a “Gas OPEC”—going beyond the current Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) to coordinate the market—is no longer implausible. In an oversupplied, competitive market, coordination among major gas producers is becoming more appealing. While their commercial strategies differ, growing pressure from electrification, renewable expansion, and decarbonization could push gas producers toward informal alignment. Rather than adopting formal OPEC-style quotas, a Gas OPEC+ could focus on softer tools: timing new investments, controlling volumes to prevent price collapses, investing in each other’s export infrastructure (as Saudi Arabia has begun doing in the United States), and defending gas’s role as a “transition fuel.”

However, forging such an alliance faces significant structural and geopolitical hurdles. The United States and Russia remain fierce competitors in gas markets, despite some discussions on gas cooperation. The United States has capitalized on Russia’s diminished presence in Europe and continues to constrain its LNG expansion. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia is only beginning to enter the global LNG market and has no plans to export domestic gas. Any such arrangement would also need to account for Qatar, the world’s second-largest LNG exporter, whose willingness to join a coordinated effort remains uncertain.

Unlike oil, natural gas markets are far more fragmented. Regional hubs, such as Henry Hub in the United States, the Title Transfer Facility in Europe, and the Japan Korea Marker in Asia, set prices rather than a global benchmark, and demand is considerably more price elastic. LNG’s flexibility and the fragmented U.S. LNG sector also make coordinated supply management more complex. Nevertheless, informal alliances, tactical dialogues, and strategic messaging could emerge as gas exporters recognize the growing existential threat of energy transition policies, especially in Europe and China.

China as the ElectroState

In contrast to the three PetroStates, China has been electrifying its economy at a remarkable speed—particularly in transportation. By 2023, its electrification rate reached twenty-six percent, surpassing both Europe and the United States, and China now accounts for roughly one-third of global electricity demand. It leads the world in renewable capacity, hosting forty-three percent of installed solar and wind infrastructure, and is rapidly expanding its nuclear fleet—representing about fourteen percent of global nuclear capacity by 2024 and half of all nuclear construction underway worldwide. It controls over eighty percent of solar manufacturing and battery supply chains and processes most of the critical minerals essential for the energy transition. For any country seeking to decarbonize (unlike the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Russia), China is an indispensable partner—or a geopolitical constraint.

While still the world’s largest importer of oil and natural gas, China`s long-term trajectory suggests a pivot: from hydrocarbon-dependent power to a commanding force in an electrified global order.

Two Parallel Energy Alliances?

What is emerging are two competing models of energy and influence—one anchored in the enduring logic of hydrocarbons, the other in the accelerating promise of electrification. At stake is not just the future of energy systems, but the contours of geopolitical power in the decades ahead.

Relations with China

China is the leading ElectroState, yet it also remains the world’s largest oil and gas importer and the most important market for PetroStates. Interestingly, both Saudi Arabia and Russia maintain strong energy ties with China. Over the past decade, Saudi Arabia and China have deepened their energy relationship. Saudi Aramco signed long-term crude supply agreements and invested in Chinese refining and petrochemical projects to secure stable demand. China has also become Saudi Arabia’s largest oil customer, strengthening a relationship that increasingly blends energy trade with broader economic and strategic cooperation, notably under the Belt and Road Initiative.

Similarly, Russia and China have significantly expanded their cooperation in oil and gas. Western sanctions, following Moscow’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, prompted a pivot eastward, culminating in the Power of Siberia gas pipeline deal. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine and subsequent bans on its oil imports by the European Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States, record-high seaborne oil deliveries have made China Russia’s largest energy customer, cementing a mutually beneficial, though asymmetrical, partnership.

In contrast, the United States, once expected to become a major LNG supplier to China, saw that trajectory disrupted following the tit-for-tat tariff war between both countries: U.S. tariffs reaching 145 percent and Chinese tariffs reaching 125 percent, including on U.S. LNG. Despite a ninety-day reprieve, tariffs remain and have effectively halted U.S. LNGexports to China, undermining what was once seen as a promising pillar of bilateral energy cooperation.

Amid negotiations over a Ukraine peace deal, persistent rumours suggest the United States may explore reviving the Nord Stream 2 pipeline. At first glance, this would appear to run counter to U.S. LNG exporters ‘ interests. However, the strategic calculus may be broader: facilitating the return of Russian gas to Europe could serve to drive a wedge between Russia and China and become a starting point for the real gas OPEC. From this perspective, reduced U.S. LNG exports might be an acceptable trade-off in pursuit of larger geopolitical objectives.

The Energy Bipolar World

A new form of energy bipolarity is emerging. On one side, the PetroStates—the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Russia—are doubling down on fossil fuels and exports. On the other hand, the ElectroStates—led by China and increasingly joined by Europe—are building dominance through electrification, large-scale renewables, and control over clean tech supply chains. This asymmetrical rivalry between hydrocarbons and electrons extends beyond energy systems, reflecting deeper contests over global influence, economic resilience, and economic models.

Fossil fuels may be the old instruments of power, while electrons and critical minerals are the new. Yet the picture is more complex. All these countries pursue hybrid strategies. PetroStates are trying to diversify: Saudi Arabia is investing in carbon capture and hydrogen, while the U.S. picture at the state-level is more nuanced: Texas is both a large oil and gas producer and a leading renewable energy hub.

Meanwhile, China, the archetypal ElectroState, is also the world’s largest importer of oil and gas—for now. It is rapidly expanding its storage capacity and trading infrastructure to mitigate its exposure to supply disruptions or market manipulation by fossil exporters. China also remains massively dependent on coal, and the EU still imports significant volumes of gas. ElectroStates are greener in ambition than in current reality.

The key question is whether the PetroStates will be willing and able to coordinate hydrocarbon markets, rather than fight for market share amid declining demand. The PetroStates Alliance is inherently unstable. While the United States, Russia, and Saudi Arabia may find tactical alignment, their strategic interests diverge—in oil pricing, political systems, and regional goals. ElectroStates face their own tensions, including trade frictions between China and the EU and intensifying competition for clean tech leadership—both of which reflect deeper geopolitical and economic rivalries.

What lies ahead is not a binary clash but a volatile contest between legacy energy powers and new clean energy hegemonies. PetroStates may cling to pricing power and fossil revenues, but ElectroStates are capturing the commanding heights of industrial technology and green influence. Both camps are internally fractured, but it is the scale, speed, and state coordination—especially in China—that may ultimately determine the balance of power in the post-hydrocarbon global order.

About the Authors: Tatiana Mitrova and Anne-Sophie Corbeau

Tatiana Mitrova is a Research Fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy and Director of the New Energy Advancement Hub.

Anne-Sophie Corbeau is a Global Research Scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy and a visiting professor at SciencesPo.

Image: William Potter/Shutterstock