Once in a while, an artist who was successful in his time but forgotten soon after is “rediscovered” in a later era. Surprising examples of this are El Greco (1541–1614) and Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), their reputations resurrected in the mid-1800s and revered ever since.

For some younger art aficionados, the American artist Varujan Boghosian (1926–2020) could be another. Boghosian is not yet lost to history, but he is not as widely known as he once was or ought to be. He was an art-world triumph and succès d’estime in the 1950s and ’60s, when the famed Stable and Cordier & Ekstrom galleries showed his work repeatedly. His work is in the collections of MOMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Whitney, and other museums have shown his work over the years. He taught at leading universities, including a professorship at Dartmouth College from 1968 to 1995, and he received many awards and honors.

His quiet, small, personal, complex, deeply poetic art was recognized by a highly refined class of connoisseurs. Because of its exquisite literary as well as visual qualities, his art was out of step with the louder precincts of the art world.

Evidence that he was not then or now a favorite of celebrity art collectors can be found in the prices of his work today. Art of this quality, depth, and history could easily add a zero or two to the left of the decimal point and still be reasonably priced. Two concurrent exhibitions, in addition to other recent shows of his work, may change the trajectory of knowledge of and reverence for his work.

On now through May 17 at Victoria Munroe Fine Art, on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, is “Varujan Boghosian: Wood Constructions & Collage.” Until August 10 at the Armenian Museum of America in Watertown, Massachusetts, is “Fragments of Memory: The Art and Legacy of Varujan Boghosian.”

Boghosian’s métier comprises collages, assemblages, and constructions. They partake of both visual, abstract forms of communication and literary, poetic ones, usually at the same time, though sometimes leaning more toward one than the other.

The works are made up of found things and bits that the artist collected over years, from flea markets, streets, garbage containers—anywhere he might have taken a look. His studios contained thousands of these items, from which he picked to create his compositions, carving, juxtaposing, and drawing around them. His wide searching and openness to use whatever came to hand allowed unlimited potential meanings in his work. He incorporated symbols from mythology and psychology; all history of literature and art was fair game.

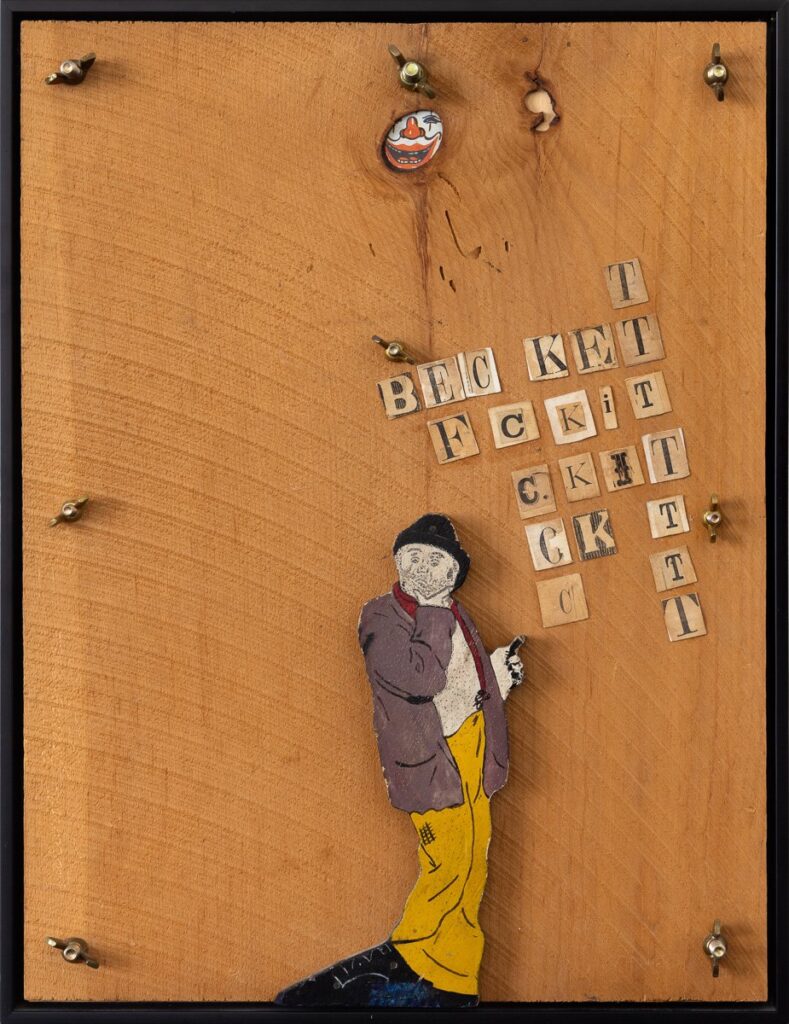

In any selection of Boghosian pieces, such as the one shown at Victoria Munroe, we find many different examples of his thinking process and originality. In Becket (2012), the intricately textured pattern of the ground is not something the artist honed, but rather the natural finish of wood he found and liked for its visual and material qualities. It is attached to its support by wing bolts, which are exposed rather than hidden, their arrangement and the irregular angles of the wings expressing both decorative and blunt, utilitarian impulses, as is characteristic of the artist’s work. An empty knothole—a flaw—in the wood surface is kept for its interesting shape and filled with a cameo image of a partial clown face. Below, Boghosian plays on the letters and typefaces in the word “Becket.” And most prominent in the composition is a cut-out, cartoonish figure that, despite the orthographic difference, brought to my mind characters from Samuel Beckett’s plays. Was this figure made (albeit not by Boghosian) to be a Beckett character, or is it a found image from a hundred or so years ago of a clochard who happens to look like Vladimir or Estragon?

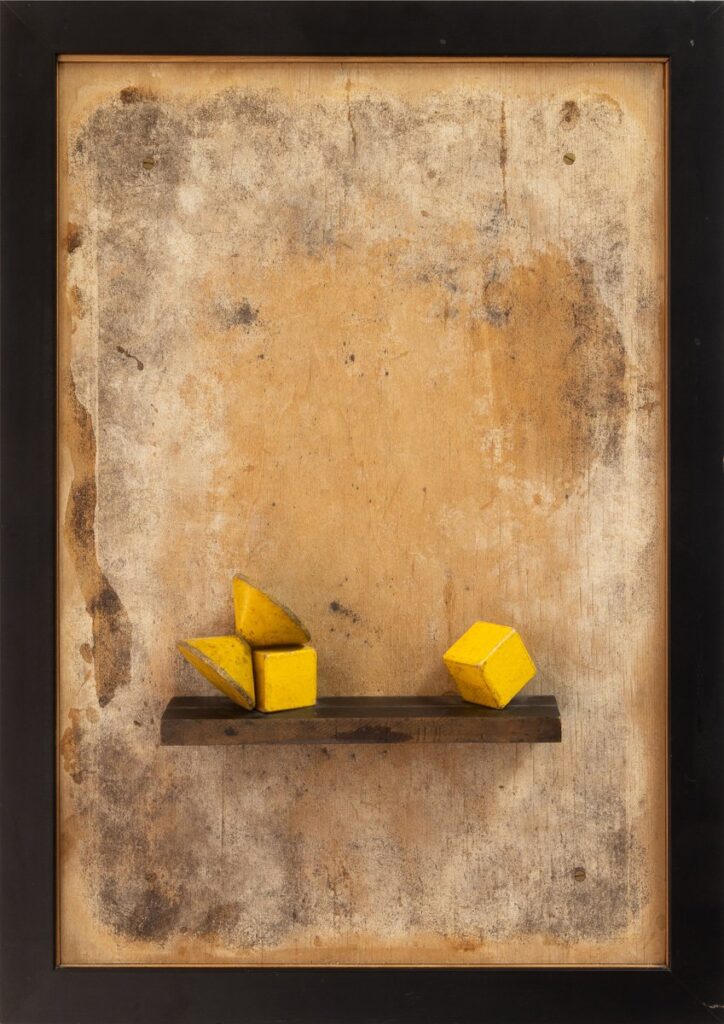

In Four Objects (2002), we see sculpture in a painting. The “background” is a complex mélange of abstract textures, which may have been found and used as is or helped along by the artist’s scraping and sanding here and there. Raising questions of balance and gravity, the four blocks do not touch each other or the support, not even the leaning twin cone. The strong parallelogram shadow of the shelf is prominent yet ethereal—it’s not always there, depending on the lighting. There are four screw heads precisely placed, one near each corner, providing a sotto voce exclamation point, or digestif, just when you think you are done looking at the artwork.

In R (2009), the usually hidden support of a canvas, its stretcher bars, is presented as assembled, wooden geometric forms. After a time, we notice that the wooden bars inserted on the lower right are shaped into an R. Or maybe we notice that first and then see how they are constructed, in forms echoed around the periphery and in the corner keys. An abstract swath of colors in the opposite corner turns out to be a moth, its icky body brightly tacked to the stretcher.

Finally, in Orpheus Descending (2009), also at Victoria Munroe, we have Orpheus—a favorite subject of Boghosian’s—as a tacky, sparkling black worm traveling through a sea of earth-colored, discarded paper shapes, its dark hue balanced by an inky abyss over the torn left edge.

Visual aspects of his work seem to be derived from Surrealism and Dada. Precedents can be found in artists like Man Ray, Max Ernst, Kurt Schwitters, and Joseph Cornell. One senses an analytic, devilish wit, something like Marcel Duchamp’s—but constructive rather than reductive. Just as important as the presence of intellect is the sensitivity to every quality of a material or object. A very subtle kind of humor emerges in a Boghosian work. The cleverness in the fine construction can bring a quiet laugh. Yet these light moments also heighten the presence of deeper concerns. Boghosian’s work often includes an underlying sadness, perhaps inherited from the Ottoman genocide of Armenians that led his parents to flee to the United States.

For much of his life, Boghosian maintained close friendships with admiring artists and writers. One of his closest friends was the poet Stanley Kunitz, who wrote a poem, “Chariot,” about his visit to his friend Varujan’s studio: “. . . the junk of lost mythologies . . . the litter spreads from wall to wall. . . . Here everything waits to be renewed.”

His art is a “wry, ambiguous, and lasting poetry,” wrote the critic John Russell in The New York Times in 1975. “Mr. Boghosian has an elegiac sense of life and brings it out to perfection in his constructions.”

About his method, intention, and attitude, the artist himself can be enlightening. He said, “I don’t make anything, I find everything,” and “I’m a junk collector. . . . I use all manner of artifacts, ancient and modern. I make constructions; I put them together.” Of his preferred media, he remarked, “I’m not a great painter. I do think I’ve added to the scheme of things with my constructions.” That is true enough, but complexity underlies deceivingly straightforward compositions whose great depth and subtlety, both visual and literary, is the result of highly refined craftsmanship. Once Varujan Boghosian meticulously selects his materials, defines their limits, and crafts them into a work, the transformed result keeps you entranced by its mystery, if you allow it to.