America’s colleges and universities have become some of the most ideologically lopsided institutions in public life. The ratio of liberal professors to conservatives rose from two-to-one in 1995 to more than six-to-one in 2019. Today, faculty are more likely to describe themselves as “far left” or “very liberal” than as being on the right.

Defenders of this status quo are either unbothered or see it as desirable. But political homogeneity threatens higher education’s primary responsibility: expanding and transmitting knowledge. If universities don’t take these imbalances seriously, they will fail the students they’re supposed to serve.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Liberal education requires a campus where students can argue with faculty and peers and dissent from prevailing orthodoxies. If students feel uncomfortable expressing themselves, or routinely self-censor, that can’t happen. The key question, then, is whether a politically homogeneous faculty effectively silences students.

Recent evidence from a small number of campuses suggests that the answer is “yes.” In a poll published in August, 88 percent of students at Northwestern University and the University of Michigan said they had “pretended to hold more progressive views” so that they could “succeed socially or academically.”

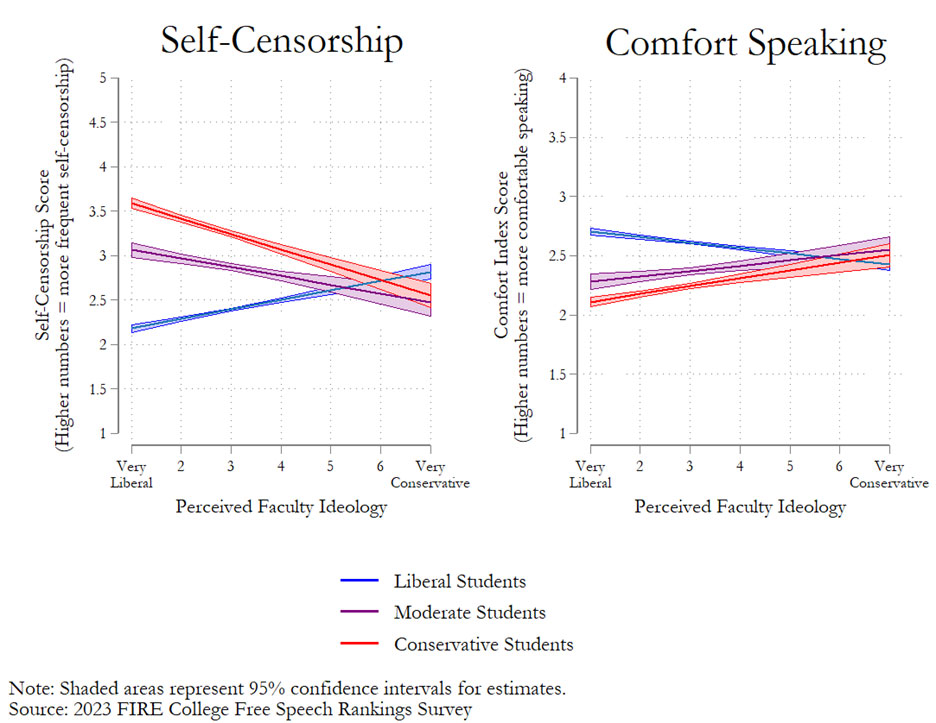

The negative impact of faculty ideological homogeneity is even clearer in data collected for the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression’s Campus Free Speech Rankings (CFSR) survey. The 2023 CFSR survey, sampling more than 43,000 students at 203 colleges and universities, asked students to rank “the political views of the average faculty member on campus” on a seven-point scale ranging from very liberal to very conservative.

Unsurprisingly, most students—69 percent of those surveyed—believe faculty members are on the left. In fact, there were only four schools in the 2023 CFSR where students considered faculty members “conservative” on average.

FIRE’s 2023 survey also included a series of questions that allow us to assess how these perceptions affect educational quality:

Self-censorship: “On your campus, how often have you felt that you could not express your opinion on a subject because of how students, a professor, or the administration would respond?”

Comfort speaking: “How comfortable would you feel doing the following on your campus? Publicly disagreeing with a professor about a controversial political topic; Expressing an unpopular political opinion to your fellow students on a social media account; Expressing your views on a controversial political topic during an in-class discussion; Expressing disagreement with one of your professors about a controversial political topic in a written assignment; Expressing your views on a controversial political topic to other students during a discussion in a common campus space.”

The figure above shows the results of regression models that predict responses to the self-censorship question and a combined index of responses to the “comfort speaking” questions. These models include controls for the individual university and for students’ demographics, socioeconomic status, and perceptions of peer ideology.

This analysis helps us determine whether students attending the same campus report systematically different experiences depending on how ideologically skewed they believe the faculty are. It also shows whether that effect is different for students who identify as liberal, moderate, or conservative.

As the graphs show, students who believe they are politically out of step with their campus’s faculty are far less comfortable expressing themselves and engage in far more self-censorship. This is not just true for conservatives but for moderates as well. When students perceive faculty as very liberal, both groups report substantially higher self-censorship than do left-leaning students. Even when faculty are seen (rarely) as “very conservative,” moderate and conservative students are about as likely as liberal students to feel comfortable.

This evidence should be a wake-up call for those who think improving ideological diversity amounts to “DEI for conservatives.” If we want campuses where students test ideas openly, we cannot treat the faculty ideological climate as irrelevant. The evidence suggests that students certainly don’t feel that way.

This is also why prospective students should weigh faculty ideological pluralism heavily when choosing a college. In the 2025 City Journal College Rankings, we included a measure of faculty political diversity. Our rankings—which combined FIRE’s 2023 CFSR survey, campaign-contribution data, and participation in Heterodox Academy and the Academic Freedom Alliance—measured the political balance of the faculty.

Using that standard, Claremont McKenna College, Pepperdine University, the University of Tulsa, the University of Notre Dame, and Washington and Lee ranked highest. Macalester College, Vassar College, Grinnell College, Haverford College, Wesleyan University, and Amherst College ranked lowest. Conservative and moderate students are more likely to experience a healthier climate for expression, disagreement, and overall learning at our highly ranked schools than at our lower ranked schools.

Those at the bottom of the list could learn a thing or two from those at the top. If they don’t, they risk alienating their students even more than they already have.

Photo by Bill Pugliano/Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link