In a conversation with a friend this last Octave of Christmas, a story by Italian philosopher Marcello Veneziani came to mind, since the two of us have been reading his latest book. The episode is recounted by the philosopher as he considers Friedrich Nietzsche, together with Karl Marx, among the thinkers who have most decisively shaped the modern world.

Christmas, 1885. In the south of France, Nietzsche spends the holiday in solitude. Far from his family, he wears a necklace of hair woven by his mother—the last fragile bond to home. When a package arrives from his family, Nietzsche’s poor eyesight betrays him; the money enclosed slips from his hands and is lost. Writing to his sister, he asks forgiveness for his clumsiness and adds a strange hope—that some poor old woman may have found the money, and along the way discovered her “Little Jesus.” (M. Veneziani, Nietzsche e Marx)

It is a revealing scene. Nietzsche, the philosopher who proclaimed the death of God and announced the coming of the Übermensch, appears not as a figure of triumphant self-mastery, but of exposed vulnerability. As Veneziani suggests, behind the rhetoric of strength and self-creation, there emerges a deeper, unresolved tension: not autonomy, but abandonment; not emancipation, but longing.

Nietzsche’s declaration of God’s death must be read in this light. It is not mere atheism, but a revolt against a particular image of God—a moralized, weakened, and life-denying idol. What Nietzsche seeks to destroy is not transcendence itself, but a false god perceived as oppressive. In this sense, his critique belongs to a much longer philosophical lineage, i.e. that of Plato.

In Book VII of the Republic, Plato describes humanity as imprisoned in a cave, mistaking shadows for reality. Liberation requires ascent: a painful conversion of the gaze toward the light. Nietzsche radicalizes this drama. For him, Christianity as he perceived it had become part of the cave—a system of shadows sustained by weakness and resentment. To free humanity, the false god must die.

Yet Nietzsche stops where Christianity begins. He imagines liberation only as ascent—through will, strength, and self-assertion, much like we can see in Plotinus’ search for the One. He cannot conceive that Truth might descend and be received as a gift. The Übermensch replaces contemplation with domination.

Here the interpretation offered by French philosopher Jean-Luc Marion becomes decisive. When Nietzsche announces the death of God, Marion argues, it is not God who dies, but an idol—a conceptual god shaped by human projection. The collapse of such an idol is not a defeat of Faith, but a purification. The false god must die so that the true God may appear.

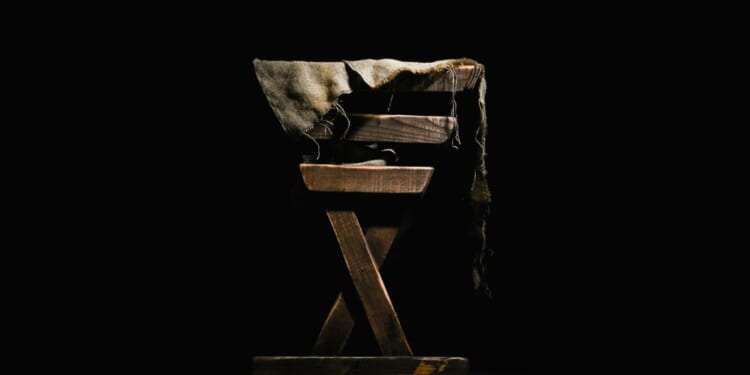

Christianity answers both Plato’s cave and Nietzsche’s revolt not by denying darkness, but by entering it. In traditional Nativity iconography, Christ is born not in an open stable, but in a cave. Humanity does not escape the cave by intellectual ascent or heroic will. The Light descends into the cave. This is where philosophy reaches its limit, and theology begins.

No one understood this more personally than St. Augustine of Hippo. In Book VII of the Confessions, St. Augustine explains that reading the Platonists freed him from materialism and taught him to seek God spiritually. Platonism, echoing the Prologue of St. John, showed him what God is like—immaterial, eternal, and luminous—but not how a sinner reaches God. It revealed the Light, yet offered no path of descent and return: no Incarnation, no grace to heal the will, and no humility by which pride could be overcome. St. Augustine could see the homeland, but he still lacked the road. Platonism taught St. Augustine where to look; only Christ taught him how a sinner is carried there. It is no wonder that St. Augustine would become the Doctor Gratiae, the “Doctor of Grace.”

The final step came only with the humility of the Incarnation. St. Augustine discovered that truth is not seized by ascent but received as a gift. The Word did not wait at the summit of intelligibility; He descended into history, into flesh, into poverty. Bethlehem completes what Athens began.

Christmas answers both philosophy’s longing and modernity’s rebellion not with argument, but with presence. Seen in this light, Nietzsche’s tragedy becomes clearer—and more human. As Veneziani suggests, Nietzsche rightly rejected a false god, but he could not accept a God who comes as a child. He could imagine the death of idols, but not the humility of grace. Yet, on that Christmas night in 1885, wearing his mother’s hair and invoking the “Little Jesus,” he stood closer to Bethlehem than his philosophy allowed.

Christmas is the moment when the cave is illuminated from within, not by the ascent of the superman but by the descent of God. The false god dies. The true God is born.

Photo by Greyson Joralemon on Unsplash