The aphorism that “you can’t please all of the people all of the time” expresses a truism that echoes through the ages. Indeed, it is especially apt for today’s tech titans.

Consider: most people appear pleased with modern digital technologies, at least if measured by behavior. Over 90 percent of U.S. adults own a smartphone and voluntarily spend $300 billion a year to use various online platforms.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Not everyone is pleased, however, with what it takes to make those platforms possible in the first place. Many people may have thought that it was all somehow “virtual,” but they now know all those platforms require massive physical infrastructure involving thousands of data centers. And now, with AI boosting the usefulness and types of platforms, there’s a rush to deploy hundreds of billions of dollars to build even more and bigger data centers. Thus, as a recent Wired headline put it, “The Data Center Resistance Has Arrived.”

It was inevitable. Data centers are no different than other infrastructures invented in the past: when they become consequential, they also become political.

Americans have fully embraced the conveniences of online shopping, learning, banking (over 80 percent of Americans use financial apps), health care, and the whole universe of productivity tools, making clear that platforms are used for many consequential tasks—not just for social media, doom-scrolling, or entertainment. Thus comes the politicization because, as with all technologies, nothing is perfect and everything entails trade-offs.

So now, as one research firm that tracks data-center opposition notes, “about 55 percent of Republicans and 45 percent of Democrats in districts with large data center projects have taken public positions against the developments.” In just one among numerous similar examples, data-center opposition recently helped Democrats flip a long-held Republican seat on the Georgia Public Service Commission. Late last year, one GOP pollster asserted that Republicans could turn a forecast 2026 loss of their House majority into a resounding gain by embracing some form of AI regulation.

Senator Bernie Sanders has enthusiastically jumped on the data-center moratorium bandwagon, intoning—in a video address carried, in no small irony, on the massive YouTube platform—that the boom is all about “the very wealthiest people on Earth” who are “pushing these technologies” because “they want more wealth, and even more power.”

Fueling the resistance movement’s theme of resentment, a featured Washington Post analysis of big tech spending observed that the money deployed on data centers “could pay for about four years’ worth of . . . the federal government program that distributes more than $90 billion in yearly food assistance to 42 million Americans.” Moreover, the paper pointed out, Nvidia’s spending alone was equivalent to the amount spent “on police, firefighters, courts, public schools and hospitals, social services, parks and more for 8.5 million people.”

Right on cue, December 2025 saw some 230 environmental groups jointly petition Congress to ban all data-center construction. Why? Because, for that constituency, the sin of data centers lies in the astonishing quantities of energy needed. (It bears noting that all of society’s useful infrastructures consume enormous amounts of energy.) Data centers are, as Fortune magazine put it, “turning local elections into fights over the future of energy.” A recent Los Angeles Times headline observed that “Gen Z can’t save the planet while doomscrolling it dry.”

A single modestly sized data center consumes more electricity than ten football stadiums. Even the low-end forecasts for the national buildout estimate that additional demand by 2032 will total more than five times the power New York City requires. Thus, data centers are being blamed for a rising electricity affordability crisis, at least according to Bloomberg News. (Many dispute this claim, including a scholar at the National Center for Energy Analytics, the think tank I lead, not least because most of the data centers haven’t even been built yet.)

The contentious issues surrounding the scale of data centers—energy, land and water usage, and aesthetics—are mixed into a witch’s brew of other well-publicized harms arising from misuses of digital technology. Hence, the politics. But while backlash is inevitable, it can’t be ignored. Today’s tech titans might take a lesson from their predecessors in the last Gilded Age on how to use their tremendous wealth for the public interest at a time of great technological disruption.

The simple, obvious fact is that even when people are pleased with a new technology’s benefits, those benefits don’t obviate concerns over associated harms, or disruptions to the status quo. History offers plenty of examples of such discontent.

Consider how many viewed (and still view) construction of highways and parking lots required for the cars everyone wants to own. Or noisy airports for aircraft, big chemical factories for life-saving pharmaceuticals, big transmission lines for remote power plants—the list goes on.

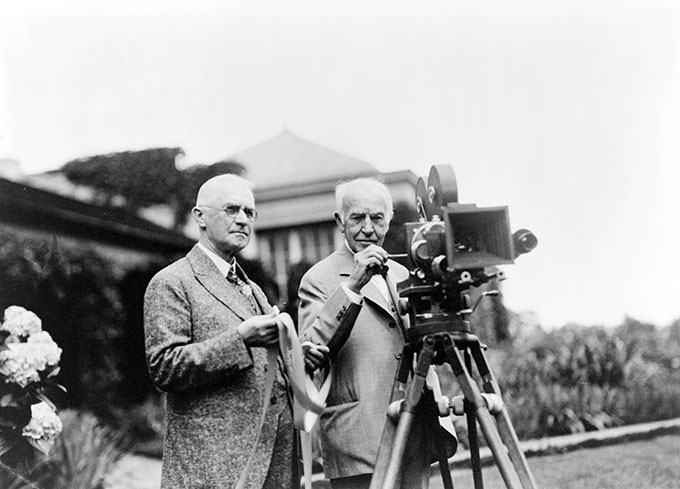

Nor is this the first time that new technologies ignited collateral anxieties over disruptions beyond aesthetics or safety. Thomas Edison’s invention of the movie camera led directly to the invention of Hollywood—but also to that era’s alarm over the destruction of vaudeville jobs, especially in New York City. The earlier invention of photography incited worries about impacts on “the arts,” the admissibility of photography as legal evidence, and what constituted property ownership, leading to seminal legal decisions regarding the nature of privacy. Given human nature, it’s difficult today to appreciate the intense emotions many of our ancestors felt upon the arrival and effects of radical new technologies.

To counter these concerns—legitimate or not—businesses today hire advisors, consultants, and lobbyists to help with education, partnerships, public relations, and old-fashioned politicking. Many of the individuals who have gained great wealth from the digital revolution also engage in forms of philanthropy, some of it as good deeds, and some of it as part of an amelioration strategy. But it’s not easy to blunt criticisms animated by resentment directed at the 0.1 percent—those whom Senator Sanders enjoys mislabeling as oligarchs.

History may offer another useful lesson here—at least regarding the kind of philanthropy commensurate with the nature of technological disruption underway.

Our era is often analogized with the Gilded Age’s asymmetric wealth creation that came from similarly deep technological transformations. In both eras, the absolute number of billionaires ballooned, and the growth rate of wealth for the top 0.1 percent exceeded the growth rate for everyone else, including the top 1 percent.

A notable feature of philanthropic behaviors by the uber-wealthy in the Gilded Age—one yet to be repeated in our time—was the many truly magnificent public gifts that were apolitical, not self-serving, and of broad, enduring value to the nation. Consider the grand philanthropic gestures of John D. Rockefeller—whose wealth at its peak was comparable to that of Elon Musk today—including his donation of hundreds of thousands of acres to create or expand America’s national parks. Rockefeller also created, with a pledge of roughly $200 million (in today’s dollars), an eponymous university in New York City to focus on biomedical research.

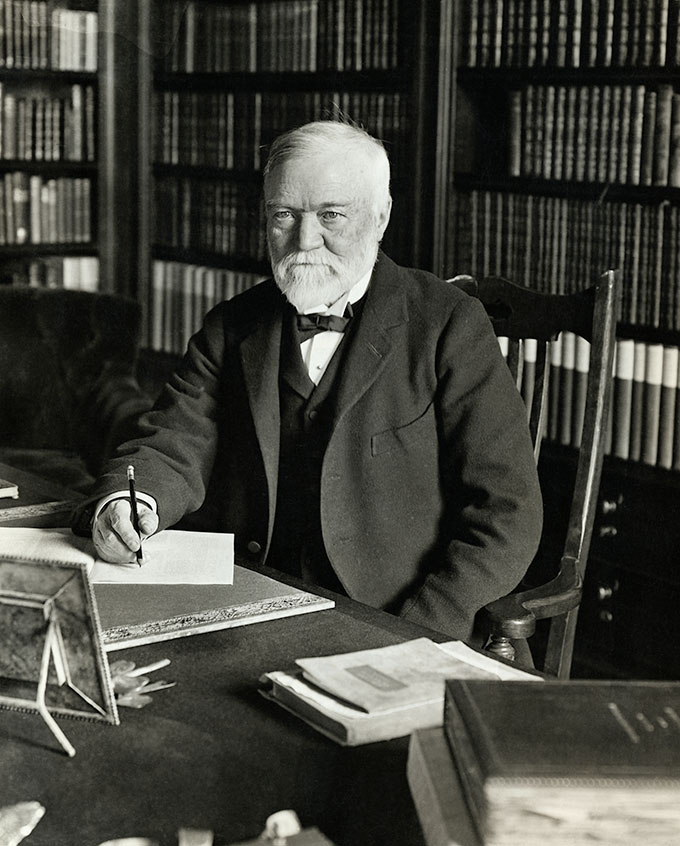

Or consider Leland Stanford’s slightly earlier multibillion-dollar gift (inflation-adjusted) establishing the university named after him, using a fortune he made on the Gold Rush and railroads. One could name many others: Andrew Carnegie, whose wealth rivaled Rockefeller’s, also founded a university. So did Ezra Cornell, using a tech fortune from his invention and production of insulators for telegraph lines and his co-founding of the telecom giant Western Union.

Carnegie, as many know, also funded another kind of educational infrastructure for the ages: more than 2,500 libraries, creating the public information superhighway of that era. Surely today’s centi-billionaires could create the modern-day equivalents of those libraries.

The “big tech” companies of the early twentieth century also had well-funded, curiosity-centric, basic research departments—focused not just on product or consumer research. Dozens of researchers at those companies earned Nobel prizes, including at Bell Labs, IBM, GE, DuPont, RCA, Xerox PARC, Ford, and Exxon. Thus far, just one Nobel has emerged from a tech firm—at Google. As I wrote ten years ago, “The mantra of Silicon Valley is to disrupt. It’s time for tech’s titans to put their money where their mantra is.”

Grand philanthropic gestures don’t guarantee a “get-out-of-jail-free” card for the social and political sins of the 0.1 percent. But they might help ameliorate some of the political anxieties of our time. That’s especially true if the gifts hold fast to the two key features of Gilded Era philanthropy: that they apolitically benefit everyone, and that they be of lasting value.

In his seminal book The Anatomy of Revolution, Harvard historian Clarence Crane Brinton wrote that history shows how political revolutions are typically not fomented by the poorest citizens; they don’t have the time or resources. Instead, political revolutions start when a significant fraction of the middle class becomes displeased—when, per Brinton, “they have less than they believe they deserve.”

Whether they like it or not, the tech titans and businesses at the center of the great data center and AI expansion are increasingly the locus of that displeasure.

Top Photo by: Jim West/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Source link