If God knows all future events, which, given our human understanding of linear time, would indicate He must direct all actions, how is it possible for us to have free will?

This question lies at the heart of an important philosophical and theological question of God’s omniscience versus human free will. Exploring and addressing this paradox are essential for understanding moral responsibility and divine knowledge.

In this article, I argue that understanding the paradox of free will and divine omniscience is crucial for grasping core issues in philosophical theology, especially when they challenge our conception of moral responsibility and divine knowledge. In particular, I intend to analyze how divine omniscience and free will can be understood as compatible within various philosophical and theological frameworks.

To begin, the issue of God’s omniscience and human free will confronts two central claims of classical theism: first, that God is omniscient and therefore knows all truths, including future human actions, and second, that human beings are genuinely free and morally responsible. This problem is fundamental to philosophical theology because it raises the question of how divine foreknowledge can coexist with human freedom.

At first glance, these seem difficult to reconcile. If God infallibly knows how I will act tomorrow, it appears I cannot do otherwise—and if I cannot do otherwise, my freedom and responsibility seem an illusion (Fischer, 2006). However, abandoning either divine omniscience or human freedom would have far-reaching implications for theology, ethics, and religious practice.

Upon careful philosophical and theological analysis, I suggest that divine foreknowledge and human free will can be reconciled coherently and easily.

Philosophical accounts of free will are diverse, and some may even contradict each other, but a common starting point is Robert Kane’s libertarian conception. Kane (2002) defines free will, in its strongest sense, as the ability of agents to be the ultimate originators of their actions and to have genuine alternatives available to them. Thus, based on this libertarian view, for an action to be free, it must not be determined by prior causes in such a way that the agent could not have done otherwise. In this regard, libertarianism denies that determinism—understood as the view that prior states fix every event and that the laws of nature are fixed—is compatible with robust freedom.

Many philosophers have debated the nature of free will, and the diversity of theories proposed can seem overwhelming. For instance, hard determinists and incompatibilists such as Peter van Inwagen (1983) argue that if determinism is true, then no one can ever do otherwise; hence, no one is genuinely free. Van Inwagen’s “Consequence Argument” claims that our actions are ultimately beyond our control if these represent the necessary consequences of specific laws of nature and events prior to our birth. Although Immanuel Kant (1785/1997) offered a complex perspective, he linked moral responsibility to the idea that, as rational agents, we are capable of acting in accordance with self-imposed moral laws rather than being wholly determined by natural inclinations.

As discussed above, such diversity of theories on free will shows that, while its nature is contested, many philosophers agree that freedom is closely tied to moral responsibility.

Modern literature also helps us examine the gap between divine and human perspectives. For instance, in Liu Cixin’s (2014) The Three-Body Problem, the “turkey scientist” is a turkey who carefully observes the regularities of his environment and formulates laws of physics for the Turkey World. The turkey’s laws of physics hold—until the day the farmer comes to take it away for someone’s Thanksgiving meal. Hence, the turkey’s entire scientific framework was confined within a system it did not realize was designed and controlled by an outside intelligence (Liu, 2014). In many ways, we are in a similar position regarding God. We live within a created order, dependent on God’s bounty for our very existence. However, our understanding is wholly shaped by our finite, temporal standpoint that cannot fathom God’s infiniteness.

Furthermore, we naturally imagine God as a kind of superhuman observer within time, but classical theism insists that God’s mode of existence and knowing transcends our categories altogether. The Biblical book of Sirach affirms this epistemic gap: “For many things are shown to thee above the understanding of man” (Sir 3:25, NRSV). Therefore, our inability to fully grasp how God’s infinite, atemporal knowledge relates to our finite, temporal choices reflects our cognitive limits more than any absolute incoherence in the doctrine.

On the other side of the problem, involving God’s omniscience, theism has provided a noteworthy response. In particular, Thomas Aquinas summarized the classical Christian position by holding that God knows all things—past, present, and future—in one single, simple, eternal act of understanding (Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I.q14).

This brings us to the classic paradox: If God now infallibly knows that I will perform some action A tomorrow, then it seems logically impossible for me not to do A; otherwise, God’s belief would be false, thus contradicting divine omniscience.

Let us take, for example, a doctor making a diagnosis. An expert doctor with a near-perfect diagnostic record examines a patient and confidently states, “You will have a severe migraine tomorrow evening.” Because his diagnoses have never been wrong, it seems impossible for the patient not to have a migraine the following evening. However, if the patient did not have a migraine as the doctor predicted, the doctor’s diagnosis would likely be incorrect, contradicting the notion that he provides accurate primary diagnoses. Thus, even though the migraine has not yet occurred, the doctor’s infallible knowledge appears to make it unavoidable. This scenario illustrates the contradiction between free will and foreknowledge.

Craig and Sinclair (2009) present the above as a logical problem: If the proposition “I will do A” is already valid and known by an infallible knower, then my future seems closed. Meanwhile, Roderick Chisholm (1964) emphasizes the theological side: If God’s knowledge is so comprehensive that no one can ever act otherwise, then moral responsibility appears to be undermined. John Martin Fischer (2006), however, points out a crucial distinction between foreknowledge and predetermination, arguing that to know that an event will occur is not the same as causing it to occur. For example, our knowledge of a future eclipse, based on astronomy, does not cause the eclipse. Nonetheless, as divine knowledge is taken to be infallible and eternal, not merely predictive, the problem runs deeper than ordinary cases of foreseeing.

In response to this problem, some philosophers explored the link between omniscience and freedom. This influential family of responses emphasizes that divine foreknowledge does not cause human actions. On the “timelessness” view, influenced by Boethius and developed by thinkers like Hartshorne and Reese (1953), God is not literally situated at an earlier point in time “looking ahead.” Instead, God exists outside time altogether, viewing the entire sweep of history—past, present, and future—from an eternal “now” (Aquinas, n.d.; Augustine, 1940–1949). From our standpoint, we speak of God “foreknowing” future events, but from God’s atemporal perspective, all events are known as the “present.” God’s knowledge is logically prior to our actions. On this model, our choices are free, and precisely because they are free, God eternally knows them as such.

As humans, we understand time such that the past and present are determinate, and our future actions are possibilities rather than certainties. By contrast, God’s omniscience consists in knowing all of these realities as they are. This notion vigorously protects libertarian freedom.

In conclusion, the tension between divine omniscience and human free will reveals more about the limits of human cognition than about any genuine incoherence in classical theism. By distinguishing knowledge from causation and adopting a timeless conception of God’s awareness, we can affirm that God eternally knows our choices without rendering them necessary or predetermined.

Furthermore, libertarian accounts of agency, combined with an atemporal model of divine knowledge, allow us to preserve both robust moral responsibility and a strong doctrine of omniscience. Therefore, I argue that, rather than forcing a choice between God’s foreknowledge and human freedom, philosophical theology can help us see how a richer understanding of God’s relation to time and creation makes their compatibility not only possible but theologically and philosophically plausible.

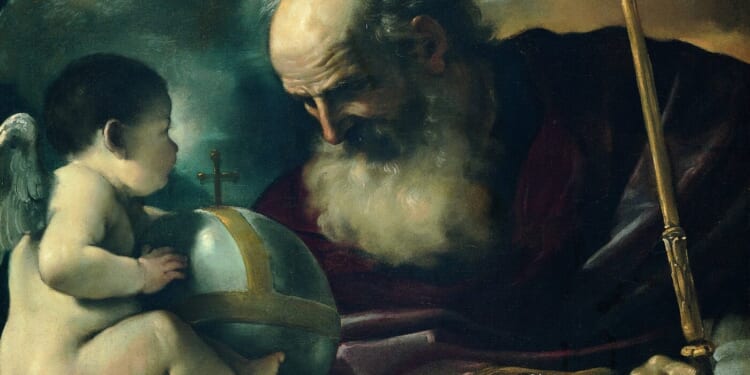

Image from Wikimedia Commons