When New Year’s Eve comes around, what do you want at the opera house? The Merry Widow? Die Fledermaus? The Metropolitan Opera staged a new production of I puritani, by Bellini. At least it has a happy ending.

It has been a good season at the Met for “the sweet Sicilian,” as Wagner called Bellini. The company had already staged La sonnambula. (For my review of the opening performance, go here.)

A review of a new production of I puritani might begin with the production—the stage direction, the set design, etc. Or it might begin with the cast, starting with the soprano portraying Elvira. But there is no element more important than the conductor. Indeed, he may be the most important element of all.

Do you know why bel canto operas such as I puritani often seem dull? Because they are dully conducted.

But not by Marco Armiliato, who was in the Met’s pit on New Year’s Eve. Year after year, decade after decade, he is reliably good. He may be taken for granted. But that would be an injustice.

The overture to I puritani is usually not a memorable affair. It would not likely appear on an orchestral program. But, under Armiliato’s baton, it was interesting, even arresting, in all its sections. It sounded like a precursor to Wagner’s Rienzi overture. Then it sounded like a Mendelssohnian scherzo. Armiliato lent the overture verve and solidity.

Every page of the opera was alive. Never did Armiliato let it sag. Never did it lose definition (not to mention momentum). This is not to be taken for granted.

Also, is there a more likable person in the music business? At the end of the evening, when Armiliato came onstage to bow and acknowledge the orchestra, he turned to the chorus behind him. The guys in the back waved at him and gave him thumbs-up.

I sensed, “They love him.”

The Elvira of the evening was Lisette Oropesa, the soprano from Louisiana. She is a star in Europe. Is she equally a star here, in her native country? I’m not sure, to be honest. In recent summers at the Salzburg Festival, she has sung the title roles of two Donizetti operas: Lucia di Lammermoor and Maria Stuarda.

In the Bellini opera, on New Year’s Eve, she displayed her worth. This “worth” includes her technical control. Her beautiful voice, which, in addition to beauty, has carrying power. Her agility. And her poise.

What is a stronger word than “poise”? Self-possession (or self-mastery). Vocal and operatic sovereignty. Many singers, you have to worry about, as you sit in your seat. This one, you don’t.

Elvira descends into madness, and this descent was compellingly brought off. In “Qui la voce,” Oropesa was liquid and heartbreaking.

Partnering her as Arturo was Lawrence Brownlee, the tenor from Youngstown, Ohio. Earlier this season at the Met, he was Tonio in The Daughter of the Regiment (Donizetti). He also substituted as Elvino in La sonnambula. Brownlee could be woken up at two in the morning to sing one of these high-flying bel canto roles and do it with ease.

Riccardo was a baritone from Poland, Artur Ruciński. He was smooth and suave—and maybe a little underpowered, in this cavernous house? (This was especially true when he was placed at the back.) In Act I, he held a concluding note for what seemed like a half-hour. This got a huge ovation.

The American bass-baritone Christian Van Horn was Giorgio—singing virilely and nobly, as is so often the case.

Not to be overlooked is the chorus, which has a significant part to play. The Met’s played it admirably. Outstanding in the orchestra were the principal French horn and the principal trumpet. They, too, have significant parts.

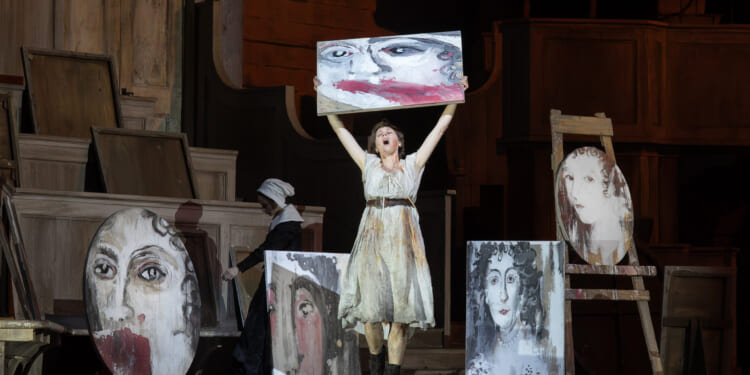

This new production is overseen by Charles Edwards, an Englishman, who is also responsible for the set design. Visually striking, this production is. It boasts a mighty fortress (to coin a phrase). Mr. Edwards clearly knows what he’s doing.

But I don’t. This production is heavy on symbolism. Pictures are drawn or painted—literally, I mean—and held aloft, and destroyed, and so on. Imaginary characters (are they?) come in and out.

What the symbols mean, the director knows, and the cast knows, and everyone else who is in the know knows. But if the audience doesn’t know . . .?

Anyway, this is an old plaint, at least from me.

Mozart died at thirty-five. Schubert, at thirty-one. Bizet: thirty-six. Bellini? Thirty-three. What if he, like these others, had had more time? In any case, he was a genius, that “sweet Sicilian” (who was also a rascal).