The Fall of Rome had a profound effect on learning and knowledge. After the fifth century A.D., philosophers scrambled to keep track of the great books of the Greco-Roman past. Most of the philosophers and scientists of the several centuries after the Fall of Rome were commentators, especially on Aristotle, and encyclopedists, preserving the information of the past.

While relying heavily on their Greek and Latin predecessors, the Early Medieval philosophers, including scientists and theologians, advanced the understanding of the Greek Logos, the Trivium and the Quadrivium, and Aristotelian thought. A few of these thinkers stand out for their advancements, especially Boethius, John Scotus Eriugena, and Isidore of Seville. These, like their forebears (such as Philo Judaeus), approached their scientific and philosophic labors by looking into God’s creation with piety.

Boethius

Boethius was a Greek philosopher living in the Latin West who was heavily influenced by Christian thinkers such as Augustine and pagan thinkers such as Aristotle. Like most ancient thinkers, Boethius believed that there is an ultimate supernatural cause for all things, which follow an inherent law: nothing is random. He therefore agreed with the Platonic and Aristotelian conception of an ultimate being or logos. He was especially influenced by the thinking of St. Augustine in his understanding of divine foreknowledge and free will, arguing that God is the creator of time, is beyond time, and therefore exists in the singular moment, able to see all events—past, present, and future—simultaneously. Before he was falsely executed for treason by the Gothic king Theodoric, Boethius wrote The Consolation of Philosophy, and planned an extensive commentary on Aristotle, of which he completed part. He studied physics, astronomy, and mathematics.

John Scotus Eriugena

John Scotus Eriugena was a philosopher, scientist, and theologian who was active in the ninth-century Carolingian Empire. Expressed in On the Division of Nature, he believed that faith in God is insufficient without reason and that Christ the Logos wholly fulfilled ancient philosophy and science. The Logos is the Creative Word through which all things come to be, and they can be understood only through faith informed through philosophy and science. Eriugena argued that the Creation is divided into five components: “a nature which creates but is not created; …a nature which creates and is created; …a nature which is created and does not create; …a nature which neither creates nor is created. …The fifth and last division is that of man into masculine and feminine. In him, namely in man, all visible and invisible creatures were constituted.” He believed in the Chain of Being—that God is the origin of all things—a truth which never changes, and that humans, as body-soul composites, are midway between the spiritual and corporeal realms, and therefore represent all things as a microcosm of the universe.

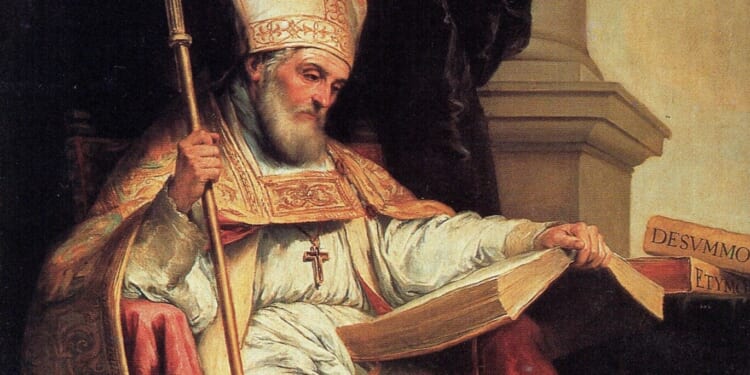

Isidore of Seville

St. Isidore, the early seventh-century (Orthodox) Bishop of Seville, was a Christian philosopher-scientist who declared that “philosophy is the knowledge of things human and divine.” Isidore put together a massive collection of writing, titled Etymologies, arguing that “a knowledge of etymology is often necessary in interpretation, for, when you see whence a name has come, you grasp its force more quickly. For every consideration of a thing is clearer when its etymology is known.” Believing that proper nomenclature is the basis for identifying and understanding all things, he set forth to acquire as much knowledge as he could. He was an encyclopedist at heart, a collector, and a commentator, especially fueled by Aristotle as well as other encyclopedic minds such as the first-century Anno Domini Roman scientist Pliny the Elder and first-century Ante Christos Roman compiler Marcus Terentius Varro.

The Trivium and Quadrivium

The work of the polymath Isidore had a lasting impact on human history, because he helped create and promote the Trivium and Quadrivium of the ancient and medieval liberal arts. The Trivium—Grammar, Rhetoric, and Logic—and the Quadrivium—Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, and Astronomy—were the bases of ancient and medieval thought, science, and education, and they continue to be the building blocks of modern educational practice even today.

Grammar to Isidore was the study of language—Greek, Latin, and Hebrew—because from it the scientist gains a working knowledge on how to proceed with analysis. Rhetoric is the expression of such knowledge so to impart it to others. Logic, or philosophy, focused on Aristotle’s dialectical methods. “Dialectic,” Isidore wrote, “is the discipline elaborated with a view of ascertaining the causes of things.” He proclaimed that “natural philosophy is the name given when the nature of each and every thing is discussed, since nothing arises contrary to nature in life, but each thing is assigned to those uses for which it was purposed by the Creator.”

Arithmetic, Isidore believed, “is the science of numbers,” and that to name and count a thing or things is the beginning of knowledge of said things. Geometry relies upon numbers to provide units of measurement in spatial relationships, especially regarding distances on Earth. Music as a philosophy and science, according to Isidore, derived from the work of the Greek philosopher Pythagoras as understood by Plato, that a harmonic “proportion exists in the universe, being constituted by the revolving circles” of the heavenly bodies. The harmonies of “the microcosm” in life and nature have “such great power than man does not exist without harmony.”

Astronomy was Isidore’s catch-all phrase for physical science, the understanding of which relies on Logic, Arithmetic, Geometry, and Music. Astronomy encompassed his geocentric understanding of the motions of the planets (the “wanderers” in Greek) in perfect spherical orbits; the science of geodesy, the shape and divisions of the earth—regions of heat and coolness; and astrology, of which Isidore was suspicious, not because it seemed an imperfect science, rather because he believed it was associated with demonology.

Medicine

Isidore was also a commentator on medicine, especially the work of the Greek Hippocrates and the Roman Galen, believing fully in the four humours—phlegm, blood, black bile, yellow bile—and how disease and illness result from the humours being out of balance. He connected the four humours with the four elements of the Greeks—earth, air, fire, and water: “each humor imitates its element: blood, air; bile, fire; black bile, earth; phlegm, water.” He also argued in Etymologies that the human “body is made up of the four elements. For earth is in the flesh; air in the breath; moisture in the blood; fire in the vital heat.” Physicians, he concluded, must be trained in the Trivium and Quadrivium to practice their art well.

Bridging Ancient and Modern Philosophy

Early Medieval European philosophy as exemplified by Boethius, Eriugena, and Isidore was an important transitional period, a bridge between the great scientific and philosophic discoveries of the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Hebrews and the Early Modern Age when the Scientific Revolution occurred. (Another transitional figure was Thomas Aquinas, who relied heavily on Early Medieval philosophers because of their focus on the Logos, Aristotle, and the Trivium and Quadrivium.) When we examine the work of Isidore, we realize that much of what he wrote was absurd; yet, in its overall scope, by the combination of ancient philosophy and science with Christian theology and his realization that scientific practice and thought are pious activities, we see how his work was essential for the future realization that understanding Nature without understanding its Creator is similarly absurd.

Editor’s Note: Read the previous installments of The Pious Scientist series here!

Image from Wikimedia Commons