Francis I: The Knight-King, by Glenn Richardson (Reaktion Books): Beloved by the French but less well known outside of his kingdom, Francis I (1494–1547) was one of the four great Renaissance monarchs who redefined European politics, religion, and culture, shepherding in the early modern period. In his new biography of the knight-king, Glenn Richardson recounts the picaresque triumphs and reversals of Francis as he battled with his nemesis Charles V of Spain in the plains of Lombardy, jousted with Henry VIII of England in Picardy, and plotted with Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent in the Mediterranean. While Francis’s political and religious strategy was not always successful, his patronage of artists and scholars such as Jean Clouet, Leonardo, and Guillaume Budé, as well as extraordinary architectural commissions such as Chambord, secured his place in history. —AG

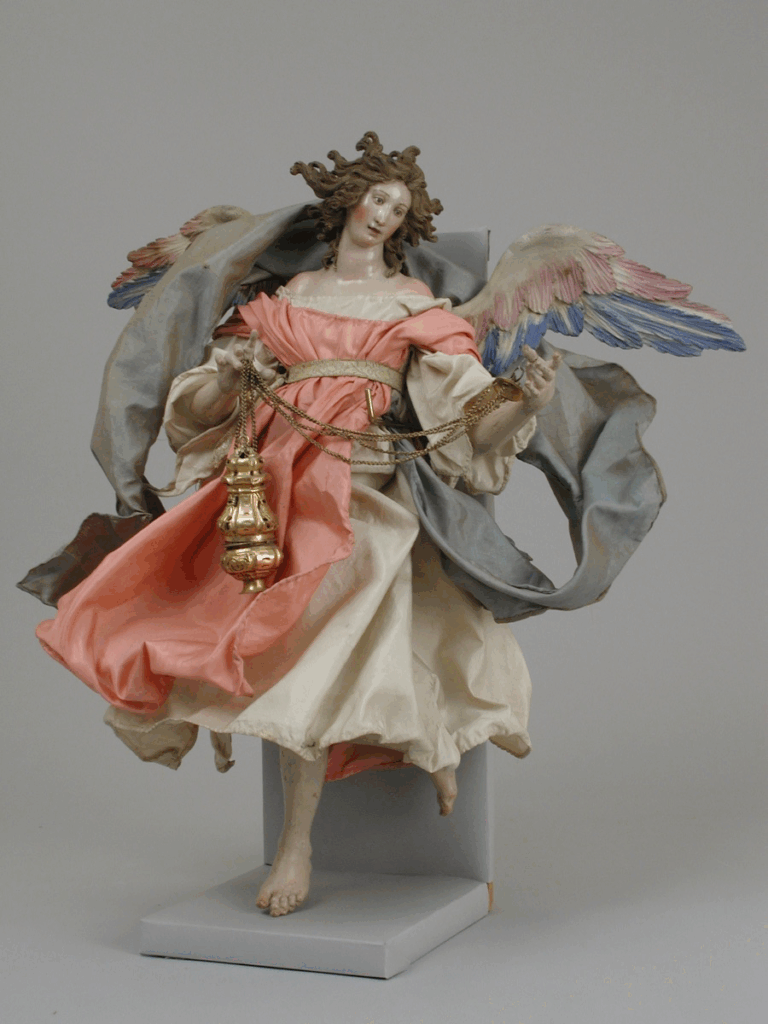

“Christmas Tree and Neapolitan Baroque Crèche,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (through January 6, 2026):Christmas may indeed come but once a year, but there is still time to see the Metropolitan Museum’s monumental yearly Christmas tree, which towers over an eighteenth-century Neapolitan nativity scene and fronts the permanent installation of the Cathedral of Valladolid’s choir screen. Stay in the spirit through January 6. —BR

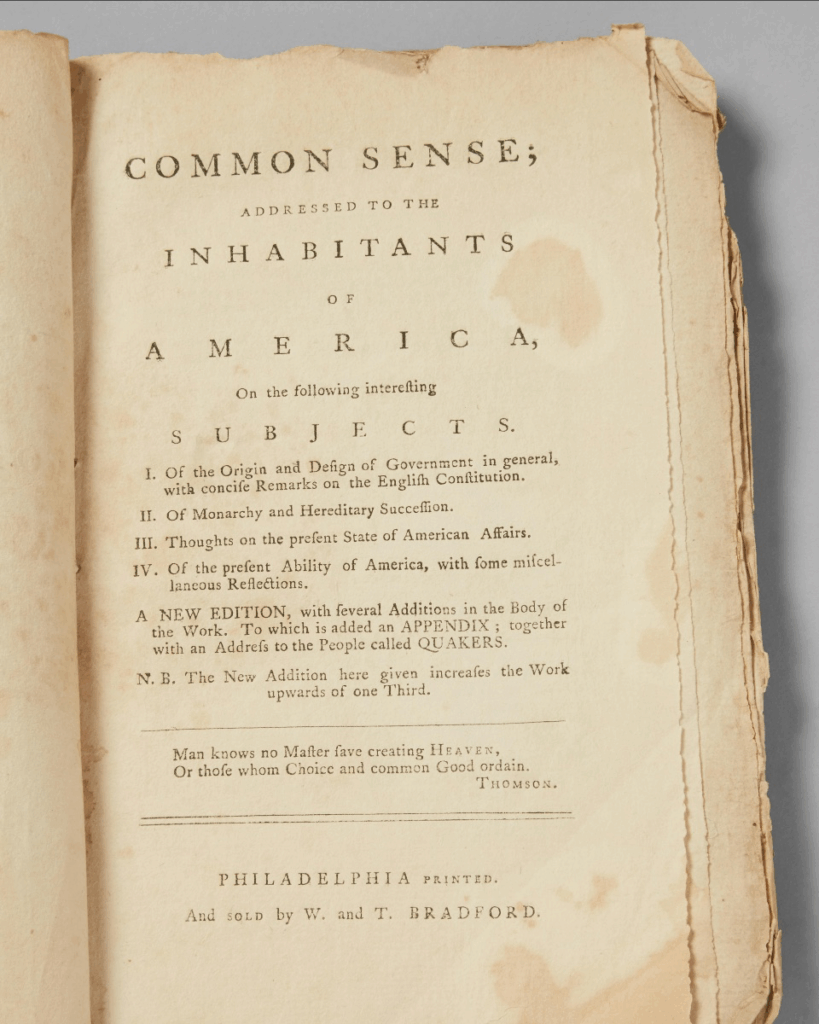

“Declaring the Revolution: America’s Printed Path to Independence,” at the New York Historical Society (through April 12, 2026): Can the written word change history? Just look to “Declaring the Revolution: America’s Printed Path to Independence,” the heart-stopping exhibition now on view at the New York Historical Society. Drawing on the extraordinary collection of the philanthropist David M. Rubenstein, the show, curated by Mazy Boroujerdi, tells the story of American independence through the documents that forged national resolve. At the center of the display are two versions of the Declaration of Independence: its first newspaper appearance in The Pennsylvania Evening Post of July 6, 1776, and the rare 1823 State Department engraving of the original engrossed copy now in the National Archives Museum in Washington, D.C. With copies of the Magna Carta and the English Bill of Rights positioned in line with the Declaration, the exhibition makes the case for American independence as a continuation of English rights and liberty.—JP

“Gil Shaham Plays Mozart,” at Lincoln Center (January 2–3, 2026): Mozart’s fame as a keyboard virtuoso has overshadowed the fact that he also diligently played the violin. His first serious job was as a violinist, and his five violin concerti, written around the age of nineteen, combine a lyrical expressiveness with instrumental facility, an early hint of the greatness to come in Don Giovanni and Figaro. Yet he soon set the instrument aside—perhaps, we can surmise, to step out of the shadow of his father, a violinist who had long prodded Mozart to practice the instrument. Gil Shaham will perform a selection of Mozart’s music for violin and orchestra on January 2 and 3 at David Geffen Hall with the New York Philharmonic, conducting at the same time, as Mozart would have done in his day. —IS

Dispatch:

“Lilies of the lagoon,” by Anatoly Grablevsky. On “Monet and Venice,” at the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

By the Editors:

“Why New Yorkers from all walks of life can put a gun on their holiday wish list”

James Panero, New York Post

From the Archives:

“The Sphinx of Athens,” by Donald Lyons (March 1995). On a new Loeb edition of Sophocles, edited & translated by Hugh Lloyd-Jones.