My family and I were living in London, in the spring of 1973, when I had to make the trip personally to purchase tickets for Tom Stoppard’s play, Jumpers. It was the play’s first performance, with Diana Rigg in the lead. On the way over the next day with my wife, I couldn’t quite recall the path to the theater from the train. I told my wife that we would simply follow another couple from the train—an academic-looking pair, with gray flecks in their hair. Sure enough, they led us straight to the right place. When a play has audiences elbowing one another as they laugh at jokes about “logical positivism,” the kind of people drawn to such entertainment can be identified fairly easily on public transport.

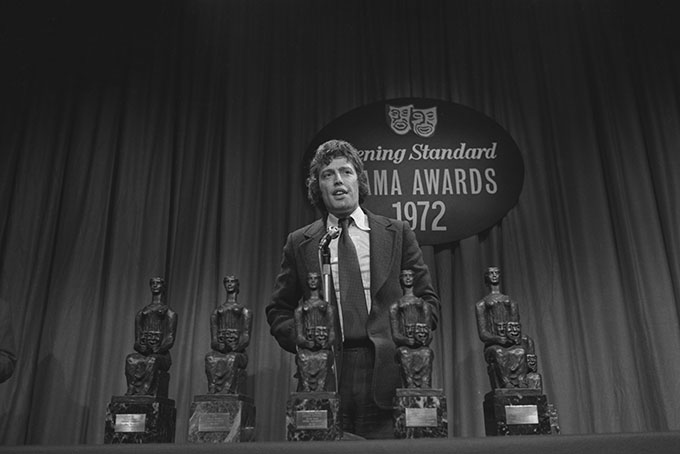

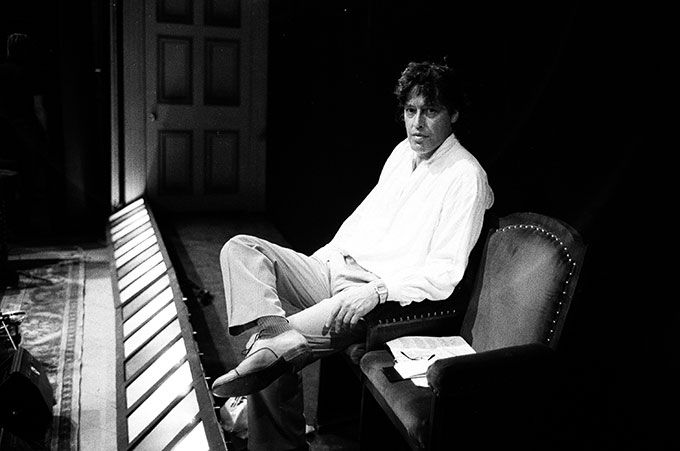

The loss of Tom Stoppard late last month at 88 is the loss of a truly unique talent—one combining serious moral insight with the most urbane wit and high comedy. He had never been, as they say, to University, but he read widely and acquired a sure command of the quarrels that flared within the academy over moral philosophy.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

Jumpers begins with the murder, in a curious setting, of a professor of philosophy. At a memorial service, his colleagues express the hope that Professor McFee will be there “in spirit”—“if only to make sure that the materialist argument is properly represented.” Over the course of the play, Stoppard also gives us an unmatchable portrait of a moral skeptic: a man reluctant to concede that the train for Bristol left Paddington Station unless he himself had been there to see it leave, for that report might be “a malicious fabrication or a collective trick of memory.” And even then, he would accept the claim only on the proviso that “all the observable phenomena associated with the train leaving Paddington could equally well be accounted for by Paddington leaving the train.”

Between 1973 and our own day, that fellow has moved from a caricature to the real thing. He walks among us, and he does such things as vote and raise children—even as he professes no sure grounds to guide his judgment on matters of right and wrong. In a country tuned to this temper, the moralist, as Stoppard says, is bound to sound like “a crank, haranguing the bus queue with the demented certitude of one blessed with privileged information.”

One of the principal characters in Jumpers is George Moore, a professor of moral philosophy, whose wife, Dottie, was once a famed actress and singer. A detective summoned to the scene to investigate McFee’s murder came in part with the hope of getting her autograph. The detective remarks to Moore that his wife, before she retired from the stage, was a “consummate artist.” But Moore replies that, regrettably, “she retired from consummation around the same time she retired from artistry.”

Still, Dottie has absorbed, with a touch of contempt, the agonies of moral philosophy that have consumed her husband and academic philosophy more broadly. In that world, as she puts it, “things can be green or square or Japanese, loud or fatal or waterproof or vanilla-flavored; and the same is true of actions, which may be disapproved of, comical, unexpected, saddening, or good television—depending on who frowns, laughs, jumps, weeps, or wouldn’t have missed it for the world. Things and actions, you understand, can have any number of real and verifiable properties. But good and bad, better and worse, these are not real properties of things; they are just expressions of our feelings about them.”

What lies at the core of the play, then, is the question of truth—truth in matters of the gravest moral judgment, and truth about the God who would be the First Cause of all things, including the moral world. All contingent things must have a beginning in something not contingent but fixed. And since material things decompose, we must be dealing with a nonmaterial, uncaused Cause of the material world. But Professor Moore, in Jumpers, notes that mathematicians are quick to point out that many series have no first term, as with the proper fractions between zero and one. “What,” they ask, “is the first, that is, the smallest, of these fractions? A billionth? A trillionth? . . . There is no beginning.”

And yet it was this notion of an infinite series that Zeno exploited in the sixth century B.C. with his famous paradox: an arrow shot toward a target must first traverse half the distance, then half of what remains, and then half again, with the result that the arrow is always approaching its target but never quite arriving. And so Saint Sebastian—the Roman centurion who converted to Christianity and converted others—was condemned by the Emperor Diocletian to be tied to a post and pierced with arrows. But if the arrows never quite reached their target, Moore surmised, Sebastian must have died mainly of fright. Yes: even contingent things have beginnings and endings.

Stoppard’s comic genius would find a rich field in exposing the vacuities offered up by intellectuals bedazzled by theories. That state of mind would come with a cold willingness to accept the vast, bloody costs of reshaping human nature to a new order of things.

This theme recurred across Stoppard’s work, finding its fullest expression in the 2002 trilogy The Coast of Utopia, a sweeping engagement with nineteenth-century political history and the ideas that planted the seeds of revolution. In the earlier drama Professional Foul (1977), Stoppard took as his backdrop the moral emptiness of the totalitarian Communist regime that ruled for most of his life in his native Czechoslovakia.

In his last performed work, 2020’s Leopoldstadt, Stoppard followed a family of Viennese Jews from the turn of the last century through two world wars and the death camps. The family sees stripped away the illusion that it had become securely settled as patriotic Austrian citizens, no longer Jews and thus no longer alien. The play was apparently stirred by a recognition—curiously late—that Stoppard’s own parents had been Jewish, one of those facts it had once been useful to conceal in a time of grave danger. It ended with a crashing finality, quite unlike the stylish cleverness that closed many of his earlier works.

In the late 1980s, I was asked to review a twelve-part series on “Ethics in America” produced by the Public Broadcasting System. Among the participants were journalists, professors, and judges—including Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who could make any program more interesting. Yet for all the lively hypotheticals, the producers arrived at little more than the conclusion that their task had been to raise questions and to remind viewers that moral judgment could indeed be a difficult business.

In striking contrast, Stoppard accomplished far more in Professional Foul, bringing out the tension between morality and mere convention. Written for television, the play had a running time of no more than 90 minutes and still had to make room for “production values.” Yet in a work meant chiefly for entertainment, with no didactic format and no pretension to instruct, Stoppard developed philosophical issues in a way far more recognizable to professional philosophers. He also managed, powerfully, to discredit the view that reduces morality to a system of etiquette or manners, to mere linguistic convention, or to the “rules of the game.”

Stoppard had his character, Professor Anderson, speak of an understanding of rightness or wrongness that “precedes utterance” and the conventions of language—“an idea of justice which is, for want of a better word, natural.” Anderson delivered these observations:

If we decline to define rights as fictions, . . . there are only two senses in which humans could be said to have rights. Firstly, humans might be said to have certain rights if they had collectively and mutually agreed to give each other these rights. This would merely mean that humanity is a rather large club with club rules, but it is not what is generally meant by human rights. It is not what Locke meant and it is not what the American Founding Fathers meant . . . when they held certain rights to be unalienable.

And yet Anderson was never fully persuaded of the existence of “natural rights” or objective moral truths. He was more inclined to the view of ethics as manners. For “ethics and manners,” he said, were “interestingly related. The history of human calumny is largely a series of breaches of good manners.” He did not find it quite “intelligible, for example, to say that a man has certain inherent individual rights.” It was, he thought, far “easier to understand how a community of individuals might decide to grant one another certain rights—rights that might or might not include, for example, the right to publish something.”

But then he suffered a jolt. He saw at close range how the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia withheld the protections of law and shabbily treated his former student, Pavel Hollar. He responded with his own crashing breach of manners: he would rewrite the paper he had prepared for an academic conference on ethics in Prague—without clearing the text with the managers of the conference.

His revised paper carried an evident critique of the Communist regime—enough to prompt the managers to feign a fire alarm and bring the professor’s lecture to an abrupt end. But Stoppard’s genius requires a closer look. Even in those revised remarks, Anderson did not actually abandon his skepticism about natural rights or objective moral truths. And yet the breach of manners was itself a performative act, speaking with a meaning of its own. Drawing on Wittgenstein, Anderson observed in another awkward moment that “language is not the only level of human communication. Whereof we cannot speak, thereof we are by no means silent.”

Stoppard was drawing his readers back to those truths that “precede utterance.” And in doing that, he was drawing us to what the great eighteenth-century philosopher Thomas Reid called the “natural language” that precedes all conventional language—for example, the outstretched hands that beckon people to come forth or hold back, or the teacher of a new language pointing to that thing in her hand and saying “book.”

In Stoppard’s play, Professor Anderson visits his former student, now condemned to cleaning lavatories in Communist Czechoslovakia. Afterward, Anderson is drawn into an odd exchange with the authorities. A cab driver has complained that Anderson asked him to wait and then failed to return and pay. Anderson does not deny what happened, but protests the charge: “How could I have told him that? I don’t speak Czech.” The detective replies, “You showed him the five on your watch, and you did all the things people do when they talk to each other without language.”

This idea of a natural language that precedes all conventional language made a deep impression on James Wilson among the American Founders, and Daniel Webster would later draw on it in recalling the case of travelers stranded by shipwreck on a deserted island. To save themselves, they made agreements about where to search, how to signal one another, and where to meet. Courts later upheld such agreements when the passengers finally reached land again. For even in the absence of lawyers and formal instruments, there was a natural sense of “contract”: people made promises to one another and staked their lives on the expectation that those promises would be honored.

In Jumpers, Stoppard had his Professor Moore musing on “the Propensity to confuse language with meaning and to conjure up a God who may have any number of predicates, including omniscience, perfection, and four-wheel drive but not, as it happens, existence.” And in The Invention of Love, Stoppard had the 19-year-old A. E. Housman, at Oxford, doing a riff for his sister on God’s words to Abraham as he showed him the Promised Land that Moses would not live to enter. And he has God telling Moses that He would give his people:

All the land of Gilead, unto Dan, and all Naphtali, and the land of Ephraim, and Manasseh, and all the land of Judah to the utmost sea, but not including Wales, which I give to the Methodists.

Stoppard’s breakthrough had come with his first, uncommonly clever play, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966), sprung from those two ill-starred characters in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. When a friend asked him, “what’s the play about?” he remarked that it was “about” to make him a lot of money.

That enduring concern would surface in Stoppard’s other plays as well, finding a resonant expression in 1974’s Travesties, set in Zurich in 1917. Stoppard plays on the historical oddity that James Joyce, the Dadaist poet Tristan Tzara, and Vladimir Lenin were all living there during the war. He weaves these strands together with echoes of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. When the British consul in Zurich, Henry Carr, is told by his butler that there has been a revolution in Russia, he asks, “What kind of revolution?” When told it is a “social revolution,” he wonders whether that means “unaccompanied women smoking at the opera, that sort of thing.” No, he is told more precisely, it is a “revolution of the classes”—of “masters and servants,” along with “scenes of violence.” To which Carr replies, with a ring of foresight later confirmed:

Well, I’m not in the least surprised. . . . I don’t wish to appear wise after the event, but anyone with half an acquaintance with Russian society could see that the day was not far off before the exploited class, disillusioned by the neglect of its interests, alarmed by the falling value of the rouble, and above all goaded beyond endurance by the insolent rapacity of its servants, should turn upon those butlers, footmen, cooks, valets.

Ah, the Hidden Injuries of the Upper Class. And why should it not have warranted the wit of our most ingenious playwright to bring it through to us?

Top Photo: Tom Stoppard in 2017 (Justin Tallis – WPA Pool /Getty Images)

Source link