One hundred and sixty-one years ago, in a forgotten farmer’s field, two elite, pioneering American special operations forces clashed: only one group would fully survive.

“You let the Yankees whip you? I’ll get hoop skirts for you! I’ll send you into the first Yankee regiment we come across!” Mosby had acidly remarked after the defeat Blazer had inflicted recently on Montjoy at the Vineyard. “The cutting words used by Mosby . . . still rang in their ears,” recalled Ranger James Williamson. The time was now ripe for vengeance.

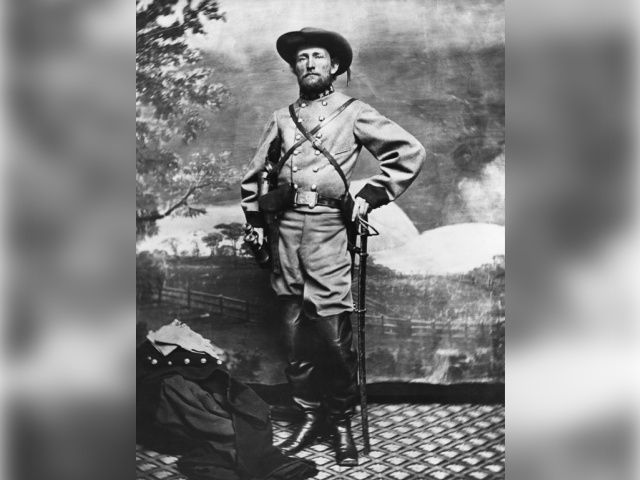

“Wipe Blazer out! Go through him!” snapped Mosby, as he issued orders to Dolly Richards from his lair at Brookside, a planation in Delaplane [which still stands], located in northern Fauquier Country. On November 16, about 300 men of Richards’ force, which included Companies A, B, and D, rode toward the West Virginia border in search of Blazer’s Independent Scouts, the U.S. Army’s first counterinsurgency unit during the Civil War. An element of the Jessie Scouts, who dressed in Confederate butternut, Blazer’s manhunters were armed with Spencer repeating rifles and had previously defeated two of Mosby’s companies of mounted guerrillas — one of the few Union units to truly stand toe to toe with the formattable Rangers.

On November 18, on the border of Virgina and West Virginia, the Rangers and Scouts hunted each other in “opposite directions of a circle.” Several companies of Mosby’s Rangers under the command of Dolly Richards soon stumbled upon Blazer’s empty camp seizing the initiative the Confederates planned to fight on the ground of their choosing.

Richards positioned his Ranger companies across a dirt road in a rolling farmer’s field skirted by woods with Company A in plain sight while Company B lay hidden at the bottom of the hill. Nearby the Shenandoah River flanked the farm in Meyerstown located near Charles Town, West Virginia. The trap was set. Richards’ carefully crafted plan unfolded as planned until a drunken Ranger dashed into the woods near the Scouts’ position, fired a shot, and galloped back to Lieutenant Hatcher, who angrily yelled at him. Blazer’s Scouts crossed the road and started to rip down two big rail fences. The Rangers coiled for their attack. Armed with their Spencer carbines and rifles, the Scouts hoped to kill from a distance. One of the Union Jessie Scouts scanned the field: “The rebs were in plain view . . . it was a desperately daring deed, and we hurried up the job, coming around into line like whip cracker.”

Charging into Blazer’s line would have been devastating, so Richards implemented a ruse to draw the Scouts into a trap. Richards ordered a few men to pull down a fence in their rear and prepare to feint a retreat moving his company off the field. Perhaps Blazer thought Company A was the entire Ranger force—in any event, taking the bait, he fatefully threw caution to the wind and ordered his men to charge.

Blazer’s men fired a volley from their Spencers. Releasing blood-curdling Rebel yells, Company B surged forward from behind the hill. “The rebs were right with us, shooting our boys down and hacking our ranks to pieces,” recalled Jessie Scout Henry Pancake. The Confederates then reversed course and charged at full speed into Blazer’s left flank. “Hand to hand combat ensued.” Time stood still for a “minute” that lasted for what seemed like an eternity, as both sides emptied “their revolvers into each other’s faces.” The Scouts “were of the true metal, however, and stood the surprise and the shock like true heroes,” recalled Ranger John Henry Alexander. Wearing Confederate butternut, Blazer’s Jessie Scouts knew that if captured, they would be considered spies and face immediate execution. Bodies hit the cold, muddy field.

Blazer tried to rally his men and stood his ground among the last of his desperate fighters. In the deadly melee, the Rangers drove the Union Scouts from the field. It was every man for himself as the Rangers hit the Scouts like an angry swarm of bees.

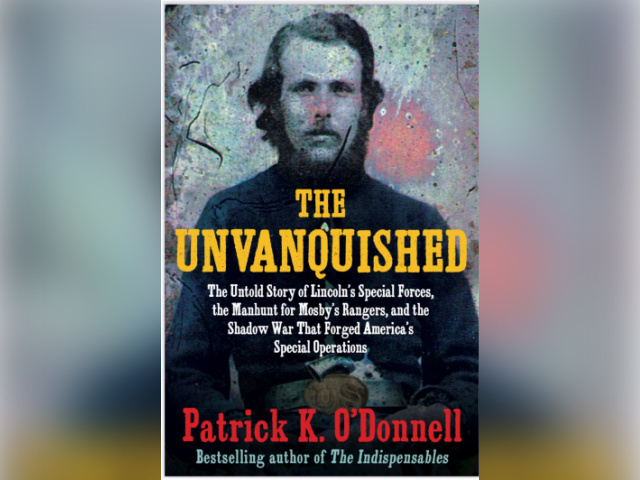

The remarkable story of this clash between Blazer’s Scouts and Mosby’s Rangers is told for the first time in its entirety in my bestselling book, The Unvanquished: The Untold Story of Lincoln’s Special Forces, the Manhunt for Mosby’s Rangers, and the Shadow War That Forged America’s Special Operations. The book reveals the drama of irregular guerrilla warfare that altered the course of the Civil War, including the story of Lincoln’s special forces who donned Confederate gray to hunt Mosby and his Confederate Rangers from 1863 to the war’s end at Appomattox—a previously untold story that inspired the creation of U.S. modern special operations in World War II.

Many of the Union troops fell in the field, but Blazer and several of his Scouts fled down the road past a blacksmith shop in Myerstown. Pancake’s uniform aided his escape, but the other Jessie Scouts rode for their lives. Then Lieutenant Coles broke from the main body of the “flying men to seek his own salvation” with Mosby’s Ranger John Puryear in hot pursuit. Earlier that morning Puryear had been captured by the Union Scouts and allegedly tortured by simulated hanging to force the Confederate to give up information on his fellow Rangers.

John Alexander caught up to Coles, who raised both hands and surrendered. Alexander leaned over to unbuckle the Union officer’s belt that contained his pistols, and as he bent over, he heard horses’ hooves behind him—it was Puryear. Rage and excitement marked the teen’s countenance. He pointed a cocked pistol at Coles’ head.

“Don’t shoot this man; he surrendered!”

“The rascal tried to hang me this morning!” retorted Puryear. Alexander asked Coles, who had been bleeding profusely from a chest wound caused by Puryear, if the statement was true. Silence. As Alexander moved, “[Coles] rolled his dying eyes toward me with a look I shall never forget, and I would gladly have tarried to give him such comfort as I could. But this was no time for sympathy, and I hurried back to the road.” Days later, Alexander found out Coles had stashed $1,800 in his clothing, and the Ranger wondered if Coles, through his stare, had attempted to give it to him for trying to save his life.

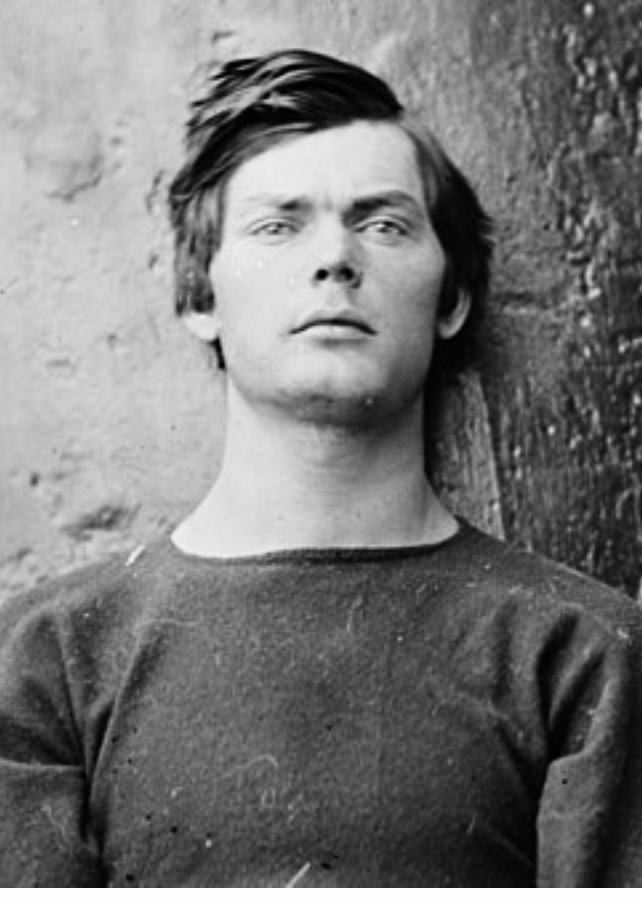

Henry Pancake galloped past Puryear as bullets from the Ranger’s pistols whizzed all around him; looking back, he saw the teen shoot the Union officer. “Only Captain Blazer and myself were left on the road, and there were 30 to 40 of Mosby’s men after us,” recalled Pancake. Within the throng, four men broke out to pursue Blazer and Pancake, “the best soldiers in Mosby’s command, Sam Alexander, Syd Ferguson, Cab Maddux, and Terrible [Lewis] Powell.” Ferguson rode a horse named Fashion, “one of the fastest and fleetest and hardiest animals in the battalion.”

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/61/JohnSMosby%26men.jpg

Blazer and Pancake sped north toward the tiny hamlet of Rippon, not far from the Berryville Pike, where Pancake gained on the Ohioan and finally caught up to him.

“Where’s the boys?” Blazer asked.

“All I know is just one behind, and I guess they’ve got him by this time,” replied Pancake. Blazer, willing to make one final sacrifice for his men, looked at Pancake and said, “I’m going to surrender.”

“I am going to get out of this,” stammered Pancake, knowing if captured he would be executed. From about thirty yards, the Rangers were peppering away at the group with their revolvers when Ferguson caught up with Blazer. Blazer’s surrender bought Pancake precious seconds to put more yards between him and his pursuers. The Jessie Scout made the ride of his life for two more miles; more men dropped out of the manhunt. “I had to beat in that horse race or die, and as there were 40 horses on the track after me.” The Rangers fired “a volley that whizzed all around me,” a last gasp as their horses wore out. Pancake looked back. Later he recalled, “I never felt so happy in my life.”

Blazer was captured by Ranger Ferguson and Lewis Powell. Nicknamed “Lewis the Terrible”, Powell was one of Mosby’s best and an operative for the Confederate Secret Service, who would take Blazer to Richmond and meet with his handlers. As a Secret Service operative, he would return north and participate with John Wilkes Booth in the Confederate Secret Service’s most daring operation to kidnap and later assassinate President Lincoln. The Unvanquished by furnishing groundbreaking evidence and links to the conspiracy.

Relieved, Pancake rode leisurely for a mile and saw a man leading a horse down the road. Of the sixteen Jessie Scouts who rode in Blazer’s Scouts, Pancake was one of the few survivors—the rest died in the fields and roads around Myerstown or were captured.

The following day, Pancake rode back to Meyerstown with a cavalry company. Twenty-two bodies were hastily buried in shallow graves1 near the blacksmith’s shop. The field where the men clashed remains an unmarked battlefield despite its significant importance to American special operations history and the hallowed ground is scheduled to house a solar panel farm.

Patrick K. O’Donnell is a bestselling, critically acclaimed military historian and an expert on elite units and special operations units. He is the author of fourteen books, including The Indispensables, Washington’s Immortals, and his latest bestselling book on Mosby’s Rangers and Lincoln’s special forces: The Unvanquished, recently published in trade paperback and featured on tables at Barnes & Noble nationwide for Christmas. He is a highly sought-after professional speaker on the American Revolution and numerous other historical topics. O’Donnell served as a combat historian in a Marine rifle platoon during the Battle of Fallujah. He has provided historical consulting for DreamWorks’ award-winning miniseries, Band of Brothers, as well as scores of documentaries and films produced by the BBC, the History Channel, and Discovery. PatrickODonnell.com @combathistorian

Epilogue: I have visited the graves of many of the men in a book:Roll of Honor, 15:234–236, details the men buried in Winchester Military Cemetery. Sixteen men from Blazer’s command who died on November 18, 1864, are buried in lot 20. Number 2001 is listed as “colored.” The body could also have been Blazer’s African American aide or a young boy who told the scouts about Mosby’s Rangers approach that morning. I have an original expense report signed by Blazer listing the aide. Lieutenant Thomas Coles was removed to Woodland Cemetery near Ironton, Ohio. Several other families brought their sons’ remains home.