Radical Dreamers: Race, Choice, and the Failure of American Education, by Joseph Viteritti (Oxford University Press, 288 pp., $29.95)

Publicly funded school-choice programs are growing rapidly across the country. More than 1.3 million students are participating in 75 state-funded school-choice programs across 35 states, 300,000 more than just a year ago. This growth has been championed by conservative elected officials, who have pushed Education Savings Account and Scholarship Tax Credit initiatives, and largely opposed by progressives, who eliminated a choice program in Illinois and opposed charter school growth in New York.

Finally, a reason to check your email.

Sign up for our free newsletter today.

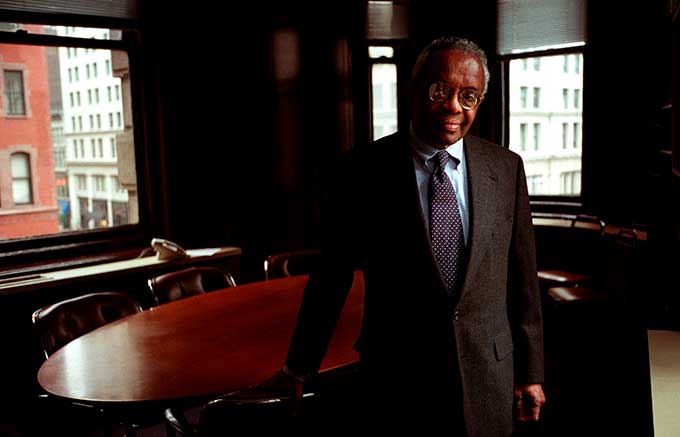

The movement for educational pluralism has not always been so polarized. As my former colleague and Hunter College political scientist Joseph Viteritti reminds us in his new book, Radical Dreamers, school choice’s early supporters included philanthropists and business leaders from the Right and black public officials and intellectuals from the far Left. This odd coalition, which seems impossible to reconstruct today, was built on compromise in pursuit of a common goal.

The progressive school-choice proponents featured in the book include Derrick Bell, considered the father of critical race theory, and Howard Fuller, founder of the short-lived Malcom X Liberation University. Fuller was an effective school reformer and practitioner in North Carolina and Wisconsin, where he found common ground with Polly Williams, a Democratic state legislator who fought successfully for the establishment of a voucher program in Milwaukee.

Bell, Fuller, and other progressives in the school-choice alliance were motivated by the civil rights movement’s failure to move beyond racial integration in schools to actual improvement in minority and low-income students’ educational outcomes. In Viteritti’s telling, civil rights organizations took their cues on education policy from “constituents”—influential individuals and organizations—rather than “clients”—families with children trapped in failing schools. The radical dreamers of the book’s title placed their faith in students and families rather than the experts.

Viteritti learned of the client-constituent dichotomy from the late Ronald Edmonds, an educator and scholar who argued that schools could overcome what many considered the social and economic impediments to low-income minority children’s educational attainment. He promoted his idea that “all children can learn” in the late 1970s as a deputy chancellor of the New York City Department of Education. Viteritti served on the chancellor’s staff; I worked on Viteritti’s team of analysts.

In the early 1980s, New York implemented school-improvement strategies based on five factors Edmonds identified as associated with effective schools: strong leadership, high expectations, an orderly atmosphere, shared priorities that placed pupil acquisition of basic skills above all else, and frequent and regular monitoring of pupil progress. These efforts achieved some success, but the city abandoned them due to budgetary constraints and leadership changes.

A similar story happened in Houston, as described in a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed by economist Roland Fryer. Fryer had studied successful charter schools in the early 2010s. The city applied his findings to its worst-performing schools, with considerable success: student math achievement quickly rose and erased racial achievement gaps, though reading improvement lagged. Unfortunately, a change in district leadership brought an end to the program after just two years.

While Fryer and Edmonds identified different criteria for effectiveness, both emphasized that schools should set high expectations of students and align their curriculum and practices accordingly. What Edmonds and Fryer both observed, decades apart, is that while educational improvement is possible, large traditional school systems have been unable or unwilling to adopt the practices that could sustain this improvement. School choice offers an escape hatch, allowing families to seek better options.

Viteritti himself is wary of universal school choice and would prefer to limit choice programs to the neediest communities. But lower-income families are not the only ones who have lost faith in traditional public schools. Middle- and upper-class families have been alienated by efforts to scale back access to advanced study in the guise of equity and attempts to impinge on parental prerogatives. Publicly funded school choice has proved to be the best strategy to align parental and school values while also closing achievement gaps across racial and economic groups, and it’s hard to imagine Republican-leaning states putting the genie back in the bottle. Defenders of traditional public schools, however, will continue to try to constrain and even repeal new choice programs. School-choice advocates will have to stay politically active to maintain their gains.

Radical Dreamers is a well-written and important history of the educational choice movement. It reminds us that improving schools is possible and that reasonable voices from both sides of the political divide can contribute to that effort—if they have the courage to do so.

Top Photo by H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).

Source link