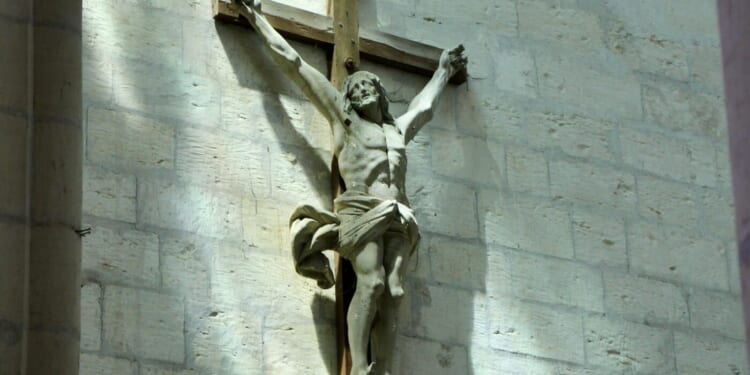

In an age where comfort is idolized and suffering is to be avoided at all costs, the Catholic crucifix remains a bold proclamation: We preach Christ crucified (1 Cor. 1:23). For many Catholics, the choice to display and venerate a crucifix—rather than a plain cross or a resurrected Christ figure—is not merely a matter of preference. It is a theological statement rooted in the heart of the Church’s liturgical and devotional life.

While the Church emphasizes the crucifix in her liturgy, it’s important to acknowledge that some people are drawn to crosses that depict the Risen Lord in glory. This image can serve as a beautiful reminder that the story does not end at Calvary. Even so, I believe there is a compelling case to be made for crucifixes that portray Christ crucified.

Do not empty the Cross of its power.

St. Paul powerfully exhorts the early Church in Corinth, “We preach Christ crucified…Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God” (1 Cor. 1:23–24). Earlier in the same chapter, he warns, “Do not allow the cross to be emptied of its power” (v. 17). These words stand in stark contrast to more sanitized or sentimentalized versions of Christian imagery. The crucifix, with the suffering body of Christ nailed to the wood, refuses to let us forget the cost of our redemption.

This central mystery of our Faith—the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus—is what the Church calls the Paschal Mystery. It is not simply a sequence of events, but one continuous, saving action. In fact, even in His glorified body, Christ retains the wounds of the crucifixion. Even the glorified, risen Lord carries the crucifixion with Him as He shows His pierced hands and side to Thomas and the other disciples (Jn. 20:27). His wounds are not erased; they are glorified.

What does the Church say?

The Church, in her liturgy, ensures that this truth is visually and spiritually represented. The General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM) states:

On or close to the altar, there is to be a cross with a figure of Christ crucified, a cross which calls to mind for the faithful the saving Passion of the Lord, and which remains near the altar even outside of liturgical celebrations. (GIRM 117)

This is no arbitrary decoration. It is a liturgical requirement. The presence of the crucifix is not meant to stir emotion alone, but to catechize and to draw all present into the mystery being celebrated on the altar: the re-presentation of Christ’s once-and-for-all sacrifice on Calvary.

The United States bishops echo this in their document Living Stones: A Guide to Building and Renovating Churches in the United States. They write:

The cross with the image of Christ crucified is a reminder of Christ’s paschal mystery. It draws us into the mystery of suffering and makes tangible our belief that our suffering, when united with the passion and death of Christ, leads to redemption. There should be a crucifix “positioned either on the altar or near it, and clearly visible to the people gathered there.” (Living Stones, §91)

This visibility matters. The crucifix is not merely a backdrop—it is a theological anchor. In beholding Christ crucified, the faithful are invited to unite their own trials, sufferings, and sacrifices with His. It reminds us that the Christian path is one of the Cross, and that resurrection only comes through Calvary.

What do the saints say?

The late Venerable Fulton J. Sheen, a powerful voice for Catholic evangelization in the 20th century, underscored the significance of this sacred image:

Keep your eyes fixed on the crucifix, for Jesus without the cross is a man without a mission, and the cross without Jesus is a burden without a reliever.

Sheen’s insight reveals a profound truth: it is precisely because the crucifix holds both the Cross and the Crucified that it is uniquely Christian.

Moreover, the crucifix is an invitation to participate. Jesus said, “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross daily and follow me” (Lk. 9:23). To gaze upon the crucifix is not to remain a spectator, but to be drawn into discipleship. It challenges us to embrace sacrificial love, to live not for ourselves but for others.

This is why Catholic crucifixes—especially in churches—ought to show Christ crucified rather than a glorified, resurrected figure hovering over the cross. The liturgy of the Mass is a participation in the sacrifice of Calvary, made present in a sacramental and unbloody manner. As such, the visual language of the sanctuary must reflect that sacred reality.

The crucifix, then, is not just art. It is not merely symbolic. It is a sacramental witness to the mystery we enter into at every Mass: the self-giving love of the Son of God poured out on the Cross, for you and for me.

In the words of Pope St. John Paul II:

The crucifix does not signify defeat or failure. It reveals to us the Love that overcomes evil and sin. It points to the One who has transformed suffering into love. (Angelus, Sept. 16, 2001)

May our churches, our homes, and our hearts be adorned with this holy image—not to glorify death, but to remember that through the Cross, love triumphed. Let us never empty the Cross of its power.

Photo by Serge Le Strat on Unsplash