The Musée Marmottan-Monet, next to the luscious Garden of Ranelagh in Paris’s Sixteenth Arrondissement, invariably presents unusual exhibitions. “The Empire of Sleep,” its current offering, focuses on sleeping and dreaming in art. The selection is also typical of the museum in mixing famous artists including Rembrandt, Picasso, Rodin, and Monet with more obscure worthies such as Gabriel von Max (1840–1915) and Giuseppe Antonio Petrini (1677–1755/59), whose St. Peter Sleeping (1740) proves that in some corners Caravaggio’s style survived the seventeenth century. An unnamed master’s exquisite Young Girl Sleeping (ca. 1615–20) shows a sweet girl wearing a dark-green garment laced with pearls resting on a richly embroidered rug. It is the exhibition’s publicity cover.

Never before has a French museum chosen sleep as a theme. Considering how much time most people spend asleep or, in the case of insomniacs, struggling to sleep, that may seem a strange oversight. “The Empire of Sleep” has plenty of history painting, while Gustave Doré’s dreamy illustrations for the Divine Comedy (1861), Don Quixote (1863), and Paradise Lost (1866) and John Tenniel’s pictures for Alice in Wonderland (1865–1871) round out the exhibition’s chosen theme nicely.

Sleep, as well as dreaming, plays an important role in the Bible. Adam was sleeping when God took a rib from him to create Eve, and sleeplessness in the Psalms indicates torment in the soul. The unsettling aspect of sleep is also notoriously explored in the story of the drunkenness of Noah, present in the show via Giovanni Bellini’s picture of the subject (ca. 1515), painted when Bellini was in his eighties. The oil shows Noah’s sons covering their very aged father with a vibrant, Venetian-red cloak redolent of incipient Tuscan Mannerism.

Ingres, Antiope and Jupiter, 1851, Oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Rembrandt’s etching Antiope and Jupiter (1659) portrays the lusty old god disguised as a satyr as he prepares to pounce on the beautiful Antiope, who, caught in a deep sleep, lies completely exposed. Robert Graves’s Greek Myths informs us that Antiope was thought to be the daughter of the River Asopus in Boeotia, though some authorities believed her to be the offspring of the Theban king Nycteus. Whatever her parentage, her sons Amphion and Zethus, born from her encounter with Zeus, went on to play a key role in the Theban cycle of myth. Ingres’ colorful rendition of the same seduction scene from 1851 has a rich blue sky and dark, luscious vegetation surrounding the action. A youthful Jupiter, accompanied by Cupid, is decisive as he boldly pushes aside a branch to have his way with the voluptuous sleeping nymph, who is bathed in clear light.

Aside from Jupiter, there are other examples of the gods’ sleeping habits on display. Lorenzo Lotto’s Apollo Sleeping with Muses Dispersing and Fame Fleeing (1530–32) suggests that even the sun god can lose his women when he sleeps on the job. Venus Sleeping on Clouds, produced by the workshop of Simon Vouet after 1630, shows an incongruous tree branch among the clouds while the most beautiful of goddesses, draped in yellow, sits up with her eyes closed and holds her head in her hand in repose. As the warm color palette of the work attests, Baroque interpretations of the classical world often have the autumnal majesty of a Scarlatti sonata.

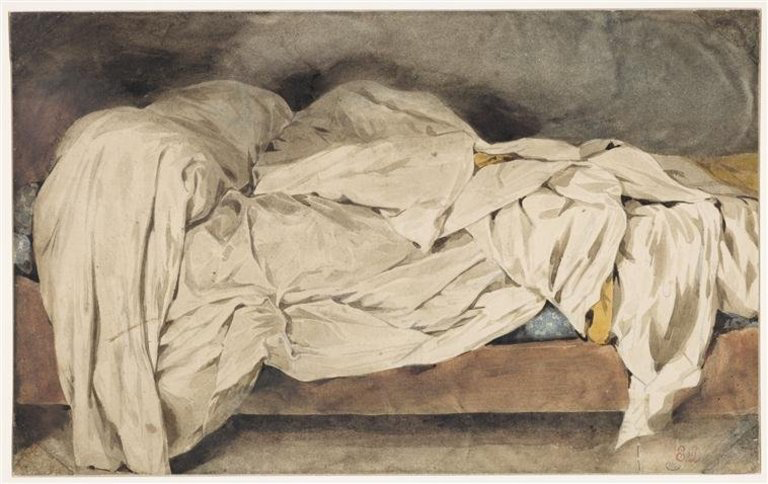

Delacroix, Unmade Bed, ca. 1824, graphite and watercolor, Louvre museum.

Ingres’ great rival, Delacroix, is present here through his graphite-and-watercolor picture titled Unmade Bed (ca. 1824), where the rumpled white sheets are somewhat plain in color, though no less turbulent than his better-known works full of color and blood. Other Romantics, such as Goya, Fuseli, and Blake, explored the darker aspects of sleep, with themes such as nightmares, murder, and madness, to push back against the eighteenth-century belief in reason. Goya’s The Dream (1790) depicts a bare-shouldered woman wearing only a gauze nightgown, her face covered in shadow and a large gold ball dangling from her shoulder. A painting by Fuseli of an incubus flying away from a waking woman (1780), from a private collection, seems almost psychological in its exploration of the delirium and torment that can characterize a night of bad sleep.

The Marmottan added Monet’s name to its title when the artist’s son Michel Monet donated the works executed by his father still in the family in 1966, and most of the museum’s exhibitions have at least one Monet. This one has two, one of Monet’s dozing ten-month-old (ca. 1860), and a strikingly sad oil (1879) of the painter’s first wife Camille laying on her deathbed, which resembles a snowstorm.

Claude Monet, Camille Monet on her Deathbed, 1879, Oil on canvas, Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

The second Monet appears in the exhibition’s middle section, which centers the twin brothers Hypnos (the Greek god of sleep) and Thanatos (the god Death). The now-unfairly neglected poet, storyteller, and anthologist Walter de la Mare disputed this genealogy in his valuable collection Behold, this Dreamer! (1939) remarking, “Death . . . far from being half-brother to Sleep, is not so much as a near relation. The two rapt countenances bear but a brief and cheating resemblance to one another.” Most people welcome sleep but dread death, all the more so as they grow older. In this respect, de la Mare quoted the seventeenth-century polymath, doctor, and master prosateur Sir Thomas Browne: “We term sleep a death, and yet it is waking that kills us, and destroys those spirits that are the house of life.”

The show’s closing wall text speaks of the changing understanding of the bed from the end of the Middle Ages, when the bedroom slowly started to become a private space, to the nineteenth century, when morality dictated a veil of modesty over any sensual associations of the bed. This original show makes for an interesting trip into the sometimes sweet, sometimes terrifying domain of the god whom the Iliad describes as “master of all the gods and mortal men.