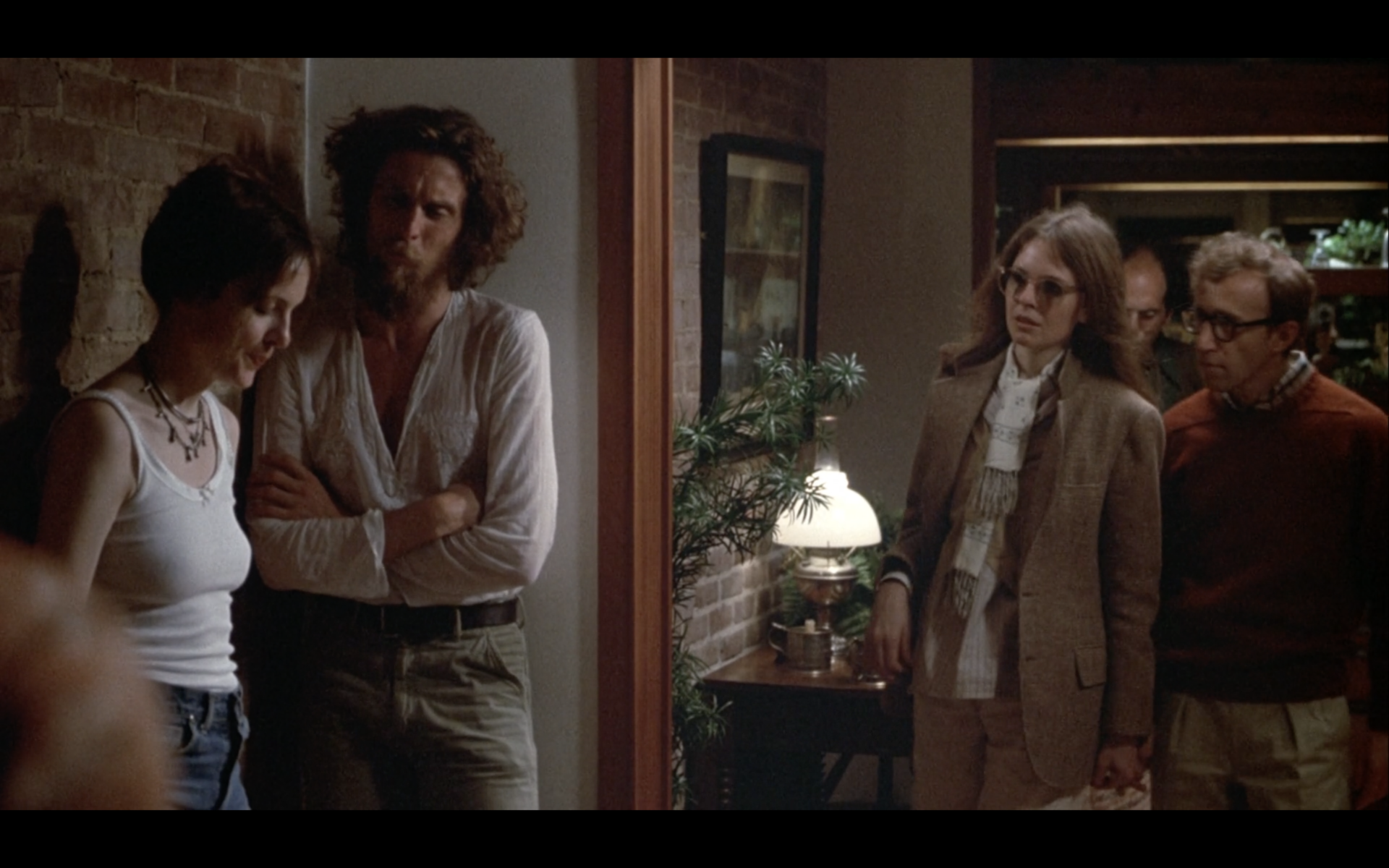

Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977) defined Diane Keaton, who died last week at 79, in the American moviegoer’s mind. The film similarly set the fashion tone for the rest of Keaton’s career — a legacy that mimics the days of Old Hollywood but that has been long gone, unfortunately.

I first got to know Diane Keaton as a young boy utterly obsessed with fashion. She was, for me at least, the floppy hat lady, the power dresser who never gave up the boxy suits quintessential to a working woman’s wardrobe in the 1980s and early 1990s.

It wasn’t until 1991’s Father of the Bride that I’d even seen Keaton in a movie. My siblings had probably rented it from Blockbuster sometime in the latter half of the 1990s with my parents’ approval.

From then on, Keaton would pop up in films throughout my childhood and well into adulthood as I caught up on movies I’d wished I’d seen when they premiered. It’s the costumes, the wardrobes set against the set design that always pulls me in.

Keaton’s eclecticism of her wide-brim hats, suits, Oxford cotton shirts, turtlenecks, wide leather belts, pleated trousers, and pencil skirts isn’t just great because she’s famous and sincerely looks good; it’s great because she dared to push through her personal style in role after role in a time where actresses are often pushed into reinvention.

In the foreword of her book “Fashion First,” Ralph Lauren, Keaton’s decades-long collaborator, wrote, “I am often credited with dressing Diane in her Oscar-winning role as Annie Hall. Not so. Annie’s style was Diane’s style.”

It’s no surprise that Keaton would actually lend costume designers her personal wardrobe for movies, letting them raid her closet to pick out outfits for scenes. What other actress living today can say they do this?

In many ways, Keaton was a throwback to a bygone era of Hollywood where Audrey Hepburn and Hubert de Givenchy collaborated in film to create the most known wardrobes in cinema history.

The same could be said for collaborations between Catherine Deneuve and the late Yves Saint Laurent, whose work together on 1967’s Belle Du Jour remains a point of inspiration for popular culture.

And, of course, who could forget the work of Roy Halston for his dear friend Liza Minnelli, particularly that short little red number in 1972’s Liza with a Z.

L’actrice française Catherine Deneuve sur le tournage du film ‘Belle de Jour’ réalisé par Luis Bunuel le 10 novembre 1966, France. (REPORTERS ASSOCIES/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

L’actrice française Catherine Deneuve sur le tournage du film ‘Belle de Jour’ réalisé par Luis Bunuel le 23 octobre 1966, France. (REPORTERS ASSOCIES/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

LIZA WITH A ‘Z’ — Pictured: Liza Minnelli — (NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images)

LIZA WITH A ‘Z’ — Pictured: Liza Minnelli — (NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images via Getty Images)

In the cases of Hepburn, Denueve, and Minnelli, it was their fondness for the designers of their time that landed their own style in their films.

Hepburn, synonymous with elegance, could have easily worn her Little Black Dress from 1961’s Breakfast at Tiffany‘s, designed by Givenchy, to the following year’s Oscars. The same can be said of Deneuve’s seamless YSL frocks and Minnelli’s bold and plunging designs from Halston.

1961: Belgian-born actress Audrey Hepburn (1929 – 1993) in a black cocktail dress designed by French couturier Hubert de Givenchy in a promotional portrait for director Blake Edwards’s film, ‘Breakfast at Tiffany’s’. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

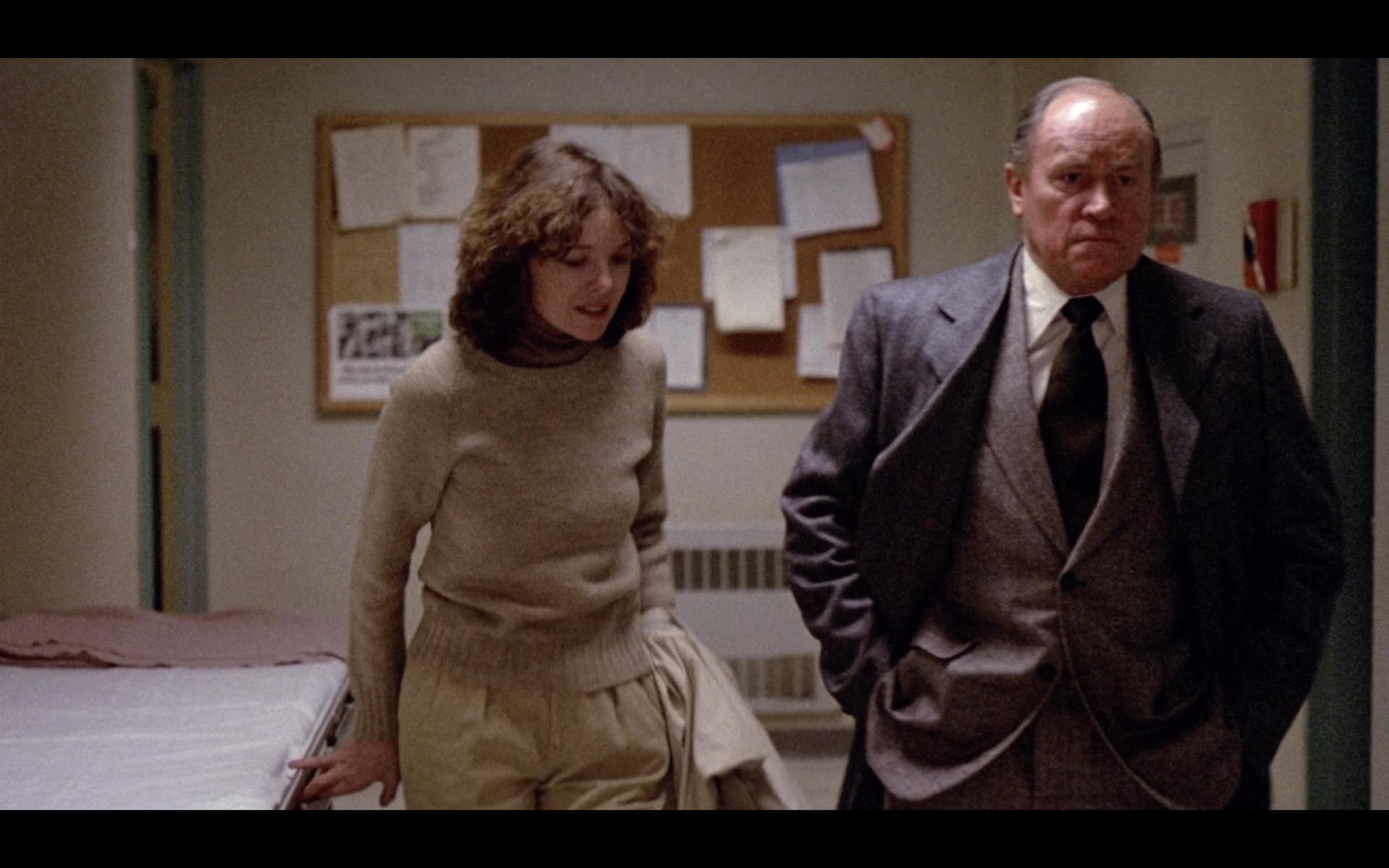

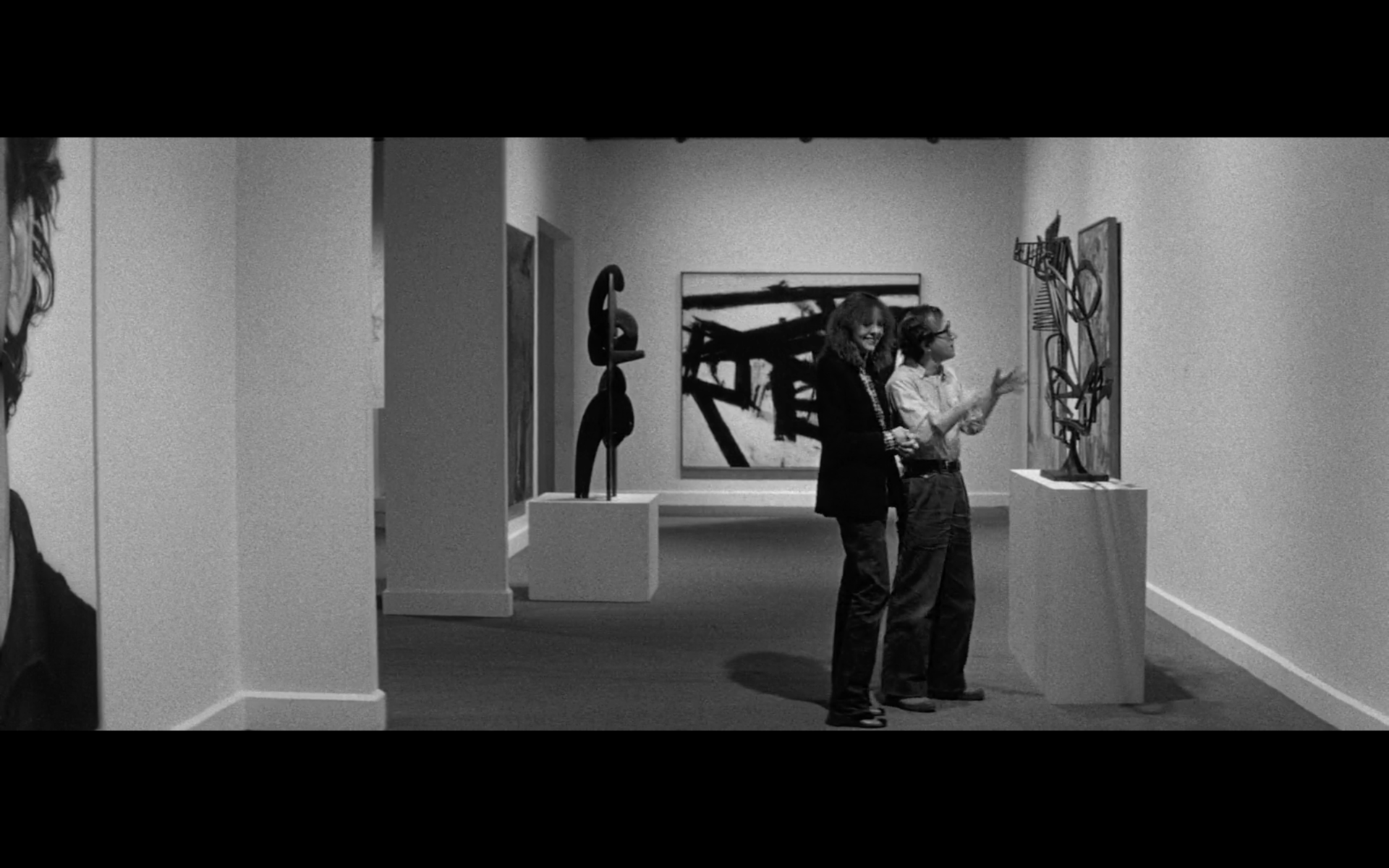

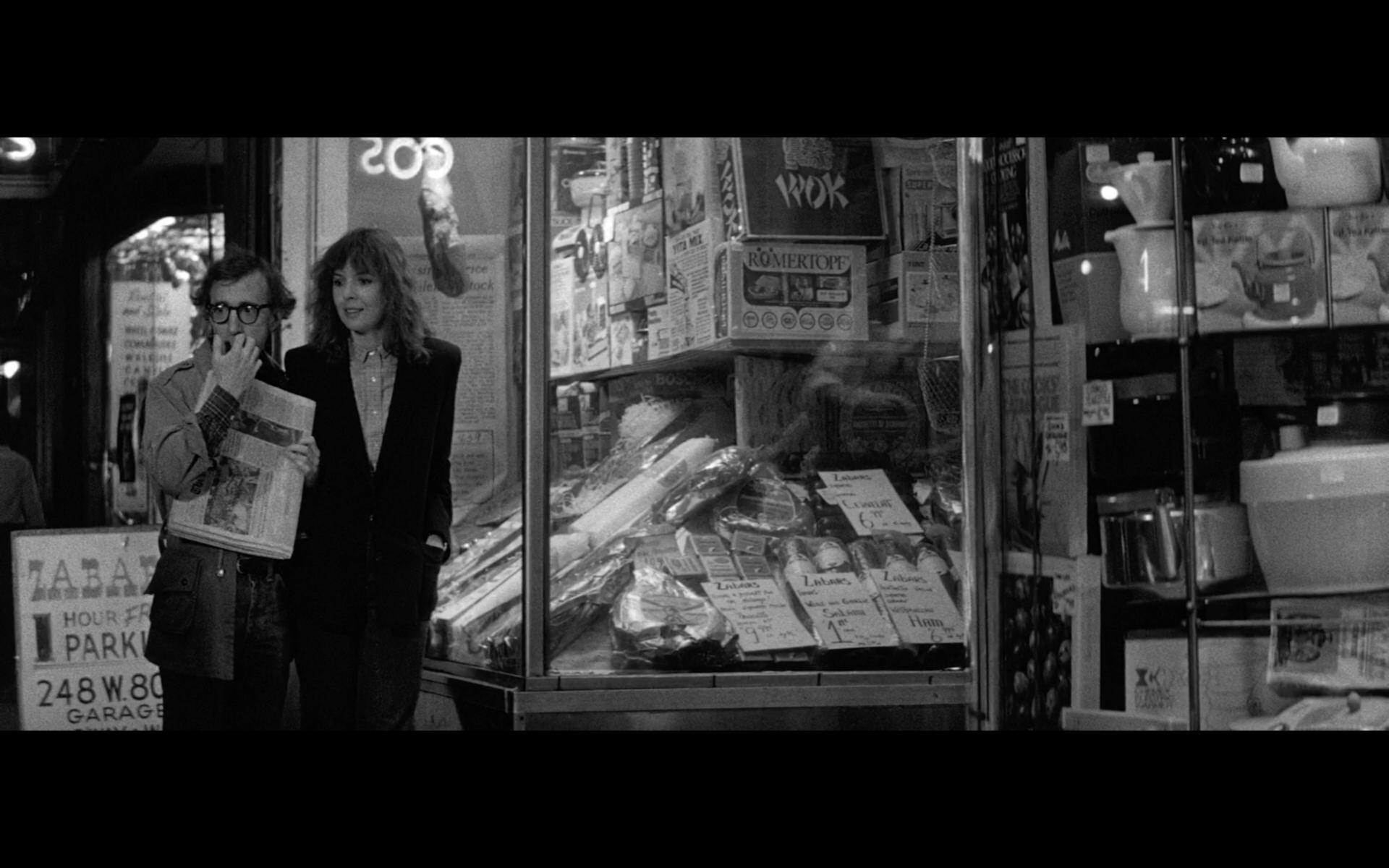

For Keaton, her style was respected by costume designers time and time again. In Woody Allen’s Interiors (1978), we see her in cozy knits and billowing pleated trousers, and later, in Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979), Keaton breaks through black and white in loads of menswear.

Just last evening, I watched 1987’s Baby Boom, a magnificent light-hearted story about a corporate yuppie who sheds the empty New York City grind for a quiet, fulfilling life with her adopted daughter in small-town Vermont.

Keaton’s New York City wardrobe is all you’d expect: Giant belts cinching skirt suits with the broadest of shoulders and long coats with even larger lapels. For her time in Vermont, Keaton gets comfier in sweaters and denim.

Perhaps Keaton’s most memorable look from her filmography, even more than Annie Hall, is the white skirt suit and matching pumps she wears to sing Lesley Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me” in 1996’s The First Wives Club.

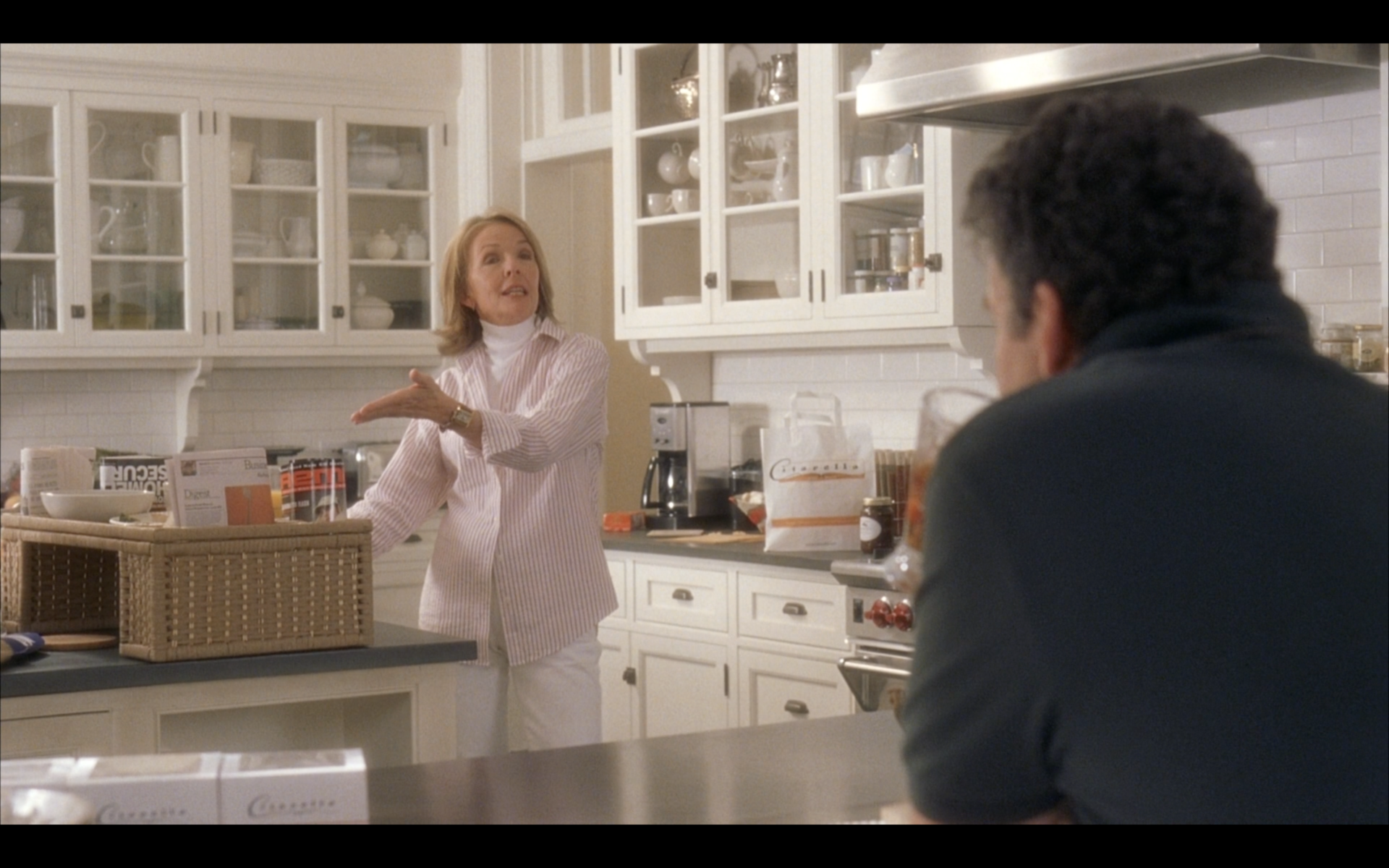

The heavy knits and jutting shoulders were ditched for Nancy Meyers’ Something’s Gotta Give (2003), where Keaton wears ivory cashmere and lightweight button-downs for this romantic comedy set in the East Coast dreaminess of the Hamptons.

In Book Club (2018) and Book Club: The Next Chapter (2023), Keaton resembled her style in recent years, a look that was almost adjacent to Gloria Steinem in the 1970s, with black and white ensembles featuring wide-leg trousers, knit blazers, and most notably, chunky belts.

The takeaway from Keaton’s decades in film and fashion, at least for me, is that she was an actress who forged an individual look in an industry of copies, fakes, and reinventors.

And not only did she forge such a path, but she made it acceptable for costume designers to let her look, well, like herself. Few can say they’ve made such a mark on cinematic fashion. Keaton did, and oh so splendidly.

When you’re as spectacular as Diane Keaton, why be a character when you can be yourself?

John Binder is a reporter for Breitbart News. Email him at jbinder@breitbart.com. Follow him on Twitter here.