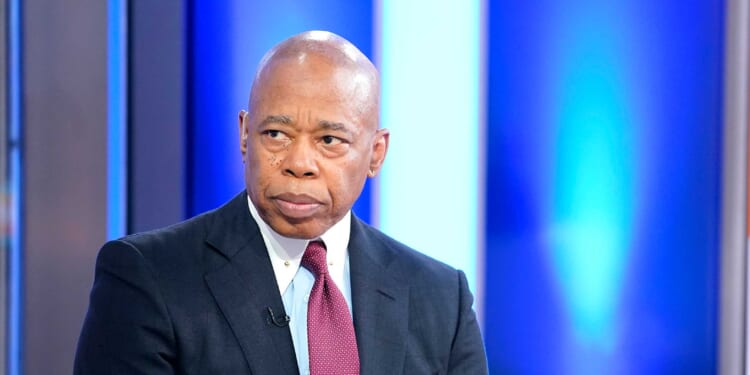

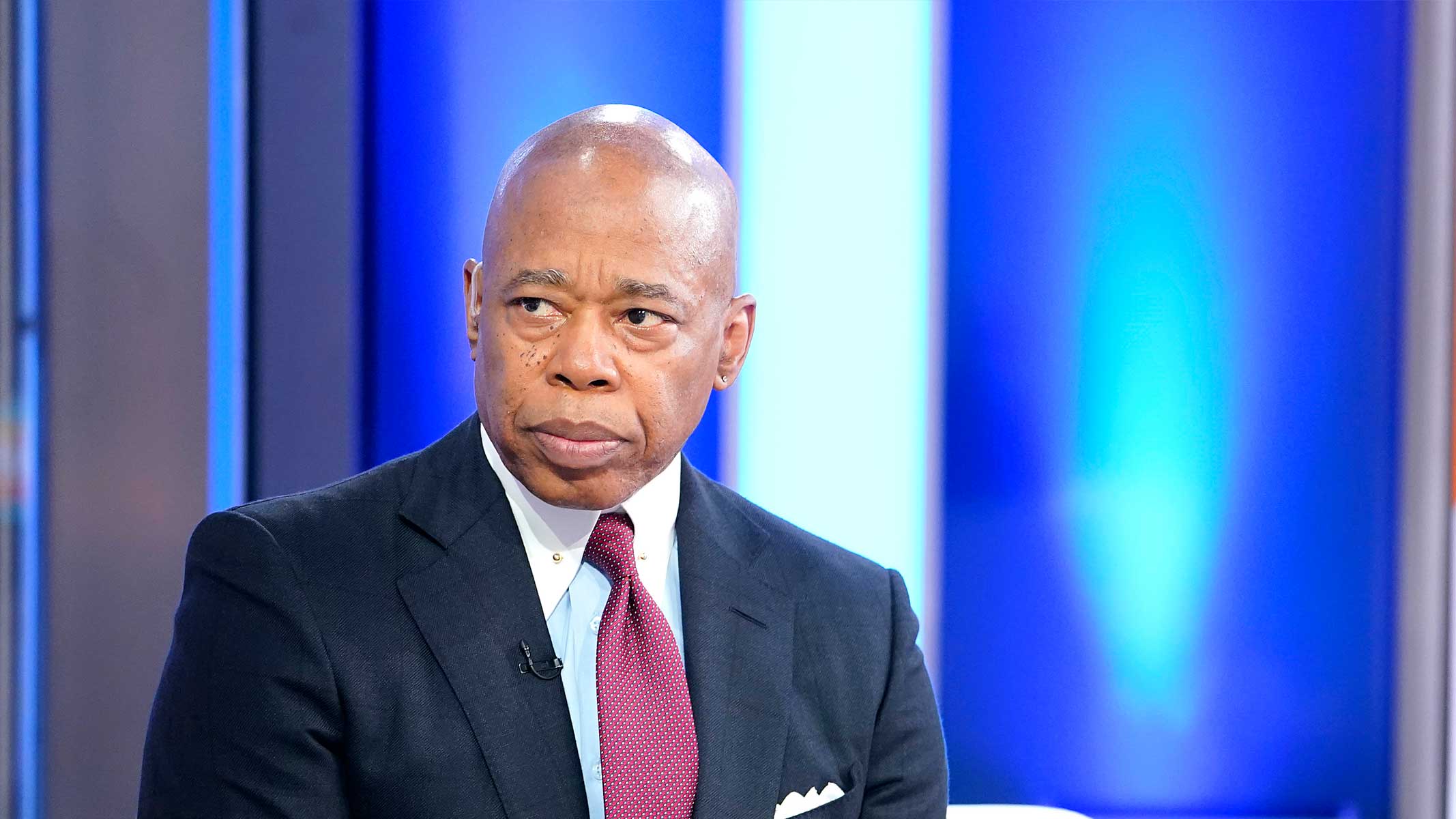

In a nine-minute midday Sunday speech, New York City mayor Eric L. Adams dropped his bid for a second term this November, saying that “I cannot continue my re-election campaign.” He’s right: his polling numbers languish in the single digits as voters remain frustrated by his erratic record and air of political corruption. But Adams’s dropout speech also oddly reminded New Yorkers of why they had voted for him in 2021, or, at least, had rooted for him after he won. Adams is authentic, likeable, and guided by a core set of admirable values and beliefs. But in governing, he could never get out of his own way, neither taking much outside advice on policy nor dropping his personal habits of petty corruption. Adams wasn’t a terrible mayor, but he could have been a genuinely good one—and his great fault is that he has opened the way for a worse successor.

In his video exiting the race, Adams showed himself to be what he’s always been: unapologetically weird. In perfectly shined black shoes and sharply tailored and creased suit pants, he descended the carpeted steps of Gracie Mansion, incongruously lugging a large object. He turned the object to face us, and we see the face of his deceased mother, Dorothy Mae Adams-Streeter. Adams set the life-sized photo portrait of her next to him as he sat at the foot of the stairs and began talking. There’s nothing wrong with honoring your mother—Adams’s died just before he won the 2021 primary—but a normal person would give this speech seated at a desk, surrounded by family photos, and, perhaps, supported by a living relative (Adams has an adult son). In this strange setting, Adams seemed furtively alone. He inhabits a mansion, presumably with multiple office desks, but preferred to make this crucial announcement on the stairs.

Adams’s enduring strangeness, though, has its appeal. In a political world that prizes authenticity and sincerity—Donald Trump is always himself, Kamala Harris and Hillary Clinton aren’t—Adams has never seemed like he was faking anything, either personally or on policy. In 2021, he won the Democratic primary and then the general election because he was the only candidate so obviously outraged by what the voters were outraged about: the city’s record increase in violent crime and disorder since the Covid-19 lockdowns of March 2020, marked most dramatically by a 53 percent increase in the murder rate. Adams’s rivals back then were too technocratic or consultant-tested, and they mostly focused on other issues. But Adams, a former police captain, was unequivocal and unfiltered, pledging that he wanted a city where “our kids could play without being hit by a stray bullet.” Voters knew that Adams had long brushed close to low-grade corruption, but he also came closest to addressing the declining public safety and quality of life that worried New Yorkers. So voters hoped for the best: that on the big stage, he would govern the city, and himself, against temptation.

He didn’t: he surrounded himself with deputy mayors and key commissioners who weren’t much interested in cultivating reputations for honesty. Last year, the Biden Justice Department indicted Adams himself on charges of taking gifts from state-controlled Turkish Airlines in exchange for doing favors for the Turkish government, a practice that had allegedly started when he held his previous office of Brooklyn borough president, and continued into his mayoralty.

Adams’s dwindling supporters along with all-purpose conspiracists allege that Biden’s appointees charged him with these crimes as retaliation. The mayor had angered Biden and his team by challenging the federal government on the open-border crisis that, starting in 2023, sent hundreds of thousands of illegal migrants seeking shelter and other aid to New York. Maybe the indictment was payback, maybe not. But Adams managed the migrant crisis poorly. He was far too slow to realize that New York’s longstanding “right-to-shelter” provision, under which the city has long agreed to provide anyone with a bed for the night, was untenable in the context of a wide-open national border. He failed to stop a top aide from allegedly using migrant-shelter contracts for self-enrichment. The city has spent $10 billion over three years on migrant costs, a sum that could have covered the entire next phase of the Second Avenue Subway.

Nor has Adams excelled on reducing crime and disorder. Yes, murders and shootings are down significantly over his tenure, with homicides in 2025 so far—at 238—running even with pre-2020 levels. But felony crime remains 28 percent above the 2019 rate. Just as seriously, Adams has never presented a long-term vision or strategy for the police department, whose ranks have dropped below 34,000, well short of record millennial levels of 40,000. Previous mayors such as Mayor David Dinkins and Mayor Rudolph Giuliani presided over big headcount increases in the NYPD. With manpower down, NYPD overtime has soared. It took Adams until his fourth police commissioner, Jessica Tisch, whom he appointed nearly a year ago, to find a competent, honest leader.

And yet: Adams’s withdrawal from the race also reminds us that we can do worse—and we very likely might. Adams, despite his flaws, believes in personal aspiration and family responsibility: “Who would have thought that a kid from south Jamaica [Queens] . . . one day could be mayor?” he said. “I cannot thank my mother enough.” He noted that “only in America can a story like this be told.” He also warned of radical ideas from extremes on the left and right: “That is not change. That is chaos,” he said.

He was clearly referring to the leading candidate to succeed him: Democratic nominee Zohran Mandani, whose proposals include moving critical police functions to social-services workers and promising an indefinite rent freeze, even as landlord costs keep rising. Mamdani wants to transfer much family and personal responsibility—extended-family care of infants, for example—to the state.

Adams has struggled to reduce overall crime in part because of the policies of Mamdani’s main rival, former governor Andrew Cuomo. Under Cuomo’s governorship, the state embraced criminal-justice leniency and continued to thwart police and prosecutors. New York City has endured three violent subway attacks in the past two weeks, including an unprovoked stabbing of a passenger in the throat, thankfully not fatal. All three were allegedly committed by people with recent violent records.

Adams’s dropping out reminds us, finally, of why he has been so exasperating. Mamdani had been running against three more moderate candidates—the mayor, Cuomo, and Republican nominee Curtis Sliwa. Adams’s departure winnows the field and makes it theoretically easier for a non-Mamdani candidate to win. But because Adams persisted in his quixotic campaign through late September, his name will remain on the November ballot, under a third party ballot line—and he may wind up garnering a few percentage points of votes in a race in which every vote could matter. Even when doing the right thing, Eric Adams still couldn’t quite manage to do it the right way.

Photo by John Lamparski/Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).