The United States ultimately canceled its bioweapons program for practical, rather than moral, reasons: bioweapons were too dangerous and too unpredictable to be weaponized responsibly.

During the peak of the Cold War, the United States briefly harbored a formal offensive biological weapons program. A manifestation of great power competition and the related anxieties, the US bioweapons program ran from World War II through the early 1970s, offering the US a string of weapons capable of inflicting mass casualties on a foreign opponent with relatively little material.

Today, the US is treaty-bound to avoid bioweapons pursuits. But declassified records confirm that the US has cultivated, tested, and stockpiled a wide array of lethal pathogens in toxins.

The US Military’s Seven Cold War Bioweapons

The program began in 1943 with the establishment of bioweapons facilities at Fort Detrick in Maryland. For two decades, researchers at Fort Detrick developed an arsenal of both lethal and incapacitating agents. By the 1960s, seven of those agents had been weaponized—most notably Bacillus anthracis, the bacterium that causes anthrax.

- Bacillus anthracis. Anthrax spores are renowned for their resilience—persisting in soil, or on equipment, for decades. As many Americans may recall from the anthrax scare of the post-9/11 era, anthrax inhalation can kill an adult quickly.

- Francisella tularensis.This bacterium is more commonly known as tularemia. Only a handful of the organisms are sufficient to cause disease.

- Brucella suis. The bacterium causes prolonged feverish illness. It spreads through aerosol dispersion.

- Coxiella burnetti. The bacterium causes Q fever. It spreads through aerosol dispersion and was believed to render troops incapable of fighting for extended periods, making it relatively straightforward for US troops to capture an irradiated area.

- Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. This virus causes severe fever and neurological symptoms.

- Botulinum toxin. More commonly known as Botox and used in microdoses in cosmetic surgery, the toxin is one of the deadliest known biological substances.

- Staphylococcal enterotoxin B. This toxin produces violent gastrointestinal illness and incapacitation.

How to Weaponize a Disease on a Battlefield

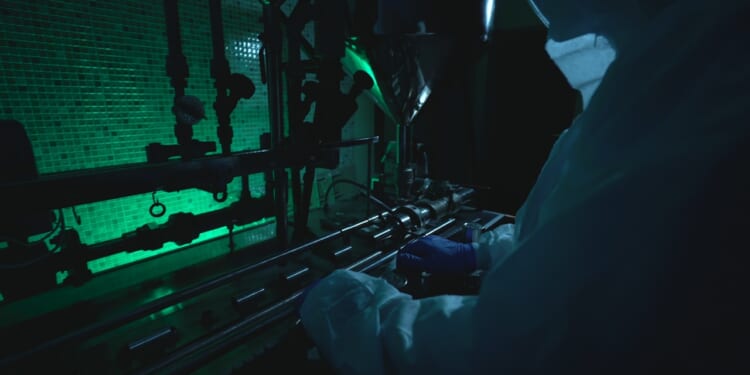

Delivery systems were developed in parallel. Military scientists engineered aerosol sprayers, closer bombs packed with bomblets filled with pathogens, and artillery shells designed to disseminate clouds of infectious material. War planners also plotted ways to contaminate food or water supplies, although this plot remained conceptual.

The emphasis for agent delivery was typically on wide-area dissemination—the ability to disperse a fine aerosol of microbes that could infest thousands of people over large distances. The military tested their delivery methods extensively. Sites like Dugway Proving Ground in Utah and Pine Bluff Arsenal in Arkansas were the central hubs for testing. Ships anchored offshore were also used as floating testbeds, where clouds of harmless bacterial stimulants were released to study dispersion patterns. But most infamously, the Army also conducted open-air trials in civilian areas—without informing the public. In one public and somewhat deranged test, Serratia marcescens, a bacterium believed to be benign, was sprayed over San Francisco to understand how effectively a city could be blanketed with microbes. One death and one infection were later linked to the test.

The bioweapons program was abruptly cut off in 1969, after President Richard Nixon announced that the US would unilaterally renounce the development and possession of bioweapons. The decision was cast as a moral and strategic imperative; bioweapons were indiscriminate, difficult to control, and raised the specter of reciprocity. Stockpiles were destroyed accordingly, and by 1973, the program had been terminated, leaving only defensive efforts.

Nixon framed the destruction as a humanitarian gesture. Yet the 37th president, an avid practitioner of realpolitik, understood that good intentions had little to do with the decision. The unilateral destruction of an entire class of deterrence weapons—at a time in US history when deterrence was most highly valued—reflected the recognition that bioweapons were simply too dangerous, and too unpredictable, to be weaponized responsibly.

About the Author: Harrison Kass

Harrison Kass is a senior defense and national security writer at The National Interest. Kass is an attorney and former political candidate who joined the US Air Force as a pilot trainee before being medically discharged. He focuses on military strategy, aerospace, and global security affairs. He holds a JD from the University of Oregon and a master’s in Global Journalism and International Relations from NYU.

Image: Shutterstock / SynthEx.