Henry Ford once declared, “History is Bunk.” Personal preferences aside, Ford’s blunt dismissal of the past reflects a still-dominant bias toward the future deeply rooted in America’s self-understanding as a nation of progress. A steep decline in the number of history majors among college undergraduates suggests that this bias remains alive and well among most educated Americans.

Ironically, recent years have also seen previously esoteric debates within the historical profession make their way to the center of today’s culture wars. In 2019, left-leaning academic historians partnered with the New York Times to produce the “1619 Project,” a work of revisionist public history that took the year of the first arrival of African slaves in Virginia as the defining moment of American history. Conservative politicians expressed outrage and, with the assistance of conservative historians, crafted an alternative, “patriotic” history, the “1776 Report.”

Is this of any concern to Catholics or the Church in America? To my knowledge, no Catholic pundit has chimed in with a strong position based on Church teaching. On the one hand, this avoids dragging the Church into the messy mud wrestling of contemporary politics. On the other hand, the silence suggests that Catholic tradition has nothing significant to say on the matter.

A distinct view of history

In this essay, I would like to argue that the Church actually does have a position in this debate. The Church has a very distinct view of history rooted in Jesus’s command to the Apostles: “Go into all the world and preach the gospel to the whole creation” (Mk 16:15). History encompasses every human activity, but the Church sees the spread of the Gospel as the highest human activity and judges historical epochs by the success or failure of fidelity to Jesus’s command.

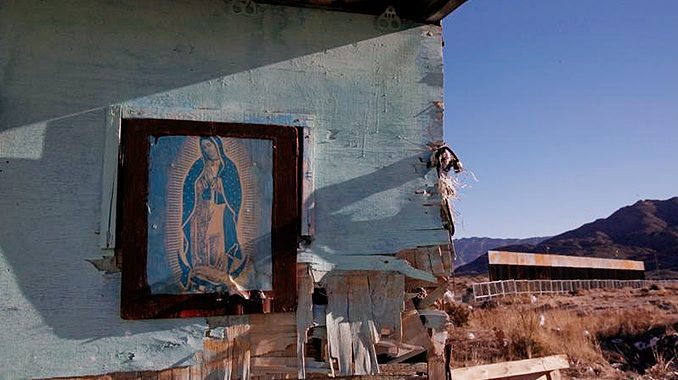

The events signified by “1619” and “1776” have a place in that history, but one subordinate to the primary story of spreading the Gospel. For a Catholic, this is not “religious history” or “Church history,” but simply history. The spread of the Gospel is itself historically contingent, finding different expressions in various places and times. For a historically appropriate intervention into current debates, I believe Catholics should look at American history through a different date: 1531, the year of the apparition of Our Lady of Guadalupe to the Indigenous peasant, Juan Diego.

The Guadalupe event does not appear in most mainstream American history textbooks. Until recently, devotion to Our Lady of Guadalupe did not figure much in the lives of non-Latino U.S. Catholics. I grew up in the 1970s. Despite the general decline in Marian devotion during that decade, my Catholic grammar school still passed on stories of Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima.

I did not learn about Our Lady of Guadalupe until high school. The priest who taught freshman Latin had been a missionary in Mexico and had a special devotion to Guadalupe; students who had not done their homework would often encourage him to tell the story of Guadalupe to escape discovery (and his pitiless wrath!). With some exceptions, Guadalupe remained a particular ethnic devotion throughout my youth and adult years. Increasing immigration from Latin America increased the visibility of Guadalupan devotion, and over the past few decades, many non-Latino U.S. Catholics have embraced Guadalupe as their own. In a surprising departure from their early efforts to downplay ethnicity in favor of a generic American Catholicism, the Knights of Columbus have in recent years promoted Guadalupe as a distinctly American devotion without minimizing its Mexican origins and traditions.

The Guadalupan event and devotion

The rise of Guadalupan devotion is a fact of American history. The Guadalupe event is a way to understand American history.

The context of this event carried with it historical and cultural dimensions distinct from all other Marian apparitions. Our Lady did not simply appear to a lowly peasant but spoke a message of love and mercy to an Indigenous convert whose people had recently experienced a catastrophic conquest by a superior Catholic power. Further, she left as evidence of her love the miraculous tilma, an image of herself with the dress and features of an Indigenous princess. As Jesus became man to suffer with us, so Mary became indigenous to suffer with a conquered people. After a decade of failed evangelization on the part of Spanish missionaries, Mary began to draw Indigenous people to the faith through an image of herself that they could recognize as one of them. Over time, despite the persistence of Spanish dominance, a distinctly New World civilization arose that blended Indigenous and Spanish elements into a new Catholic civilization.

Historians of Latin American culture call this process of mixing mestizaje. It is, in one sense, yet another example of the inculturation of the universal faith into particular cultures that has been going on since the small community of Jewish Christians in first-century Palestine brought the Gospel to the Greco-Roman civilization of the Mediterranean world. More recently, the philosopher Rocco Buttiglione has made a bolder claim: this mestizo civilization stands as a distinctly Catholic, “alternative modernity.” In contrast to cultural historians, who often fall into a romantic primitivism by privileging the pagan elements of this inculturation, Buttiglione insists that this achievement stands as distinctly Catholic and distinctly modern.

The discovery of the New World marked the beginning of modernity, shattering the geographic and cultural assumptions of a parochial and relatively unified European Christian world. Whereas some Spaniards refused to embrace the New World people, even to the point of denying their humanity (the better to exploit them through slavery), figures like Bartolomé de las Casas argued for their full humanity and the moral and spiritual necessity of integrating them into the Gospel life.

This achievement has for too long been either forgotten or taken for granted. The New World was new and troubling, but the Church embraced its newness, drawing people into the universal truth of the Church while retaining those aspects of indigenous culture compatible with the Gospel.

A different constellation of values

U.S. Catholics who find this story inspiring may wonder what it has to do with current debates about American history. I would answer: everything. In Buttiglione’s account, the modernity to which Guadalupe stands as an alternative is North America, or more pointedly, Anglo-Protestant modernity. The United States never developed anything close to a mestizo civilization with respect to its indigenous populations, opting instead for confinement of its conquered people to reservations.

Until very recently, this refusal to allow for cultural mixing also shaped, in a similar fashion, the official modern Protestant response to other pre-modern cultures that threatened its purity: namely, the culture of the immigrants who flooded into America from the 1840s to the 1920s. A significant portion of those immigrants were Catholic, who were told that to become good Americans, they had to abandon their traditional language and culture, and, ultimately, their religion. In the North American context, Catholics were the equivalent of the Indigenous peoples of Latin America: if not technically a conquered people, they were absolutely a subordinate one.

Our Lady did not bless Catholic immigrants with a miraculous apparition. Still, the spirit of Guadalupe lived on as these Catholics refused to submit to Protestant modernity and crafted their own “alternative modernity” that managed to synthesize traditional beliefs and cultural practices with something radically new: the utterly alien civilization of modern, urban industrial capitalism. This synthesis was contentious. Many Irish American clergy who heroically defended the Catholic faith would have been happy to see Italian and Polish cultural traditions pass away. Still, up until the middle of the twentieth century, Catholics maintained enough of their traditions to stand as a people apart within America—or, to use Buttiglione’s term, an “alternative modernity” within America.

This story, the extended narrative of 1531, falls far below the radar of those who debate the significance of 1619 and 1776. It draws its life from a different constellation of values, centered not on “freedom” but on community and solidarity. Sadly, this is a story little known by most American Catholics. As a scholar, I encountered the academic study of American Catholicism only after many years of laboring in “mainstream” American cultural history. It was a revelation that has inspired much of my subsequent work. The tremendous body of academic writing on American Catholic history has largely remained inaccessible to a non-academic audience. In my American Pilgrimage (Ignatius Press, 2022), I tried to synthesize this material and present it in a reader-friendly narrative format.

The Church’s greatest contribution to America

Writing a one-volume narrative history presented challenges beyond accessibility. Forsaking academic analysis for narrative raises the question: which narrative?

In this, I found myself at odds with the entire tradition of American Catholic historical writing. As I reflected in an earlier essay on history and nationalism, most historians in this tradition have narrated the story of the Church in America as the story of Catholics becoming fully American. Always kept in check by the endurance of ethnic subcultures, this Americanism finally triumphed in the 1960s. For all the divisions that have wracked the Church since the 1960s, Americanism (despite its liberal and conservative variations) is perhaps the one thing that all American Catholic can agree. For all the current talk of Catholic “identity,” Catholics have largely lost the cultural distinctiveness that once set them apart from other Americans. Whatever remains of authentic Catholic faith, it exists apart from authentic peoplehood.

What does it mean to be a people? We cannot turn back the clock, but the past provides models that can inspire future cultural renewal. There are, of course, many “pasts” from which to choose. In my study of American Catholic history, I have drawn my greatest inspiration from stories rooted in an urban, ethnic Catholic parish as it developed from the middle of the nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth. The social and cultural achievements of these communities stand as the greatest achievement of the Church in America.

In a very distinct way, it is the Church’s greatest contribution to America—not because it contributes to some larger, greater thing that is America, but because it provides America a witness to Catholic truth expressed through the endurance of traditional faith and communal culture in a modern secular world.

For much of its history, this world apart was indeed the target of anti-Catholic prejudice. Still, as that actual urban Catholic world was passing away, it gained increasing attention from the non-Catholic world. In the 1970s, Americans who had no interest in the doctrinal debates of the post-Vatican II era nonetheless flocked to movie theaters to get a glimpse of a separate urban Catholic world, usually of the Italian-gangster variation. Even as that world recedes ever further, popular artists continue to mine the cultural gold of that world. It is hard to imagine a compelling film made about post-ethnic Catholic life in America.

The interminable battles over doctrine will do nothing to address the problem of culture. In a sad variation on Berthold Brecht’s dictum, “first bread, then morality,” some contemporary Catholic activists seem to insist, “first doctrine, then culture.” Looking historically, I tend to think these people have it backward. Proper catechesis is necessary, of course, but hardly sufficient. In “Requiem for a Parish,” her classic essay on the changes in Catholic life since Vatican II, Emily Stimpson observed: “Culture, not catechesis, was the framework that held the immigrant American Catholic Church together.”

For all the current talk of Catholic culture and identity in America, I find very little engagement with actual examples of those Catholic cultures most proximate to contemporary American Catholic life. Such cultural engagement requires an engagement with history, one that flows not from 1619 or from 1776, but from 1531.

If you value the news and views Catholic World Report provides, please consider donating to support our efforts. Your contribution will help us continue to make CWR available to all readers worldwide for free, without a subscription. Thank you for your generosity!

Click here for more information on donating to CWR. Click here to sign up for our newsletter.