As schoolchildren returned to classrooms this September, New York governor Kathy Hochul celebrated the extension of free school meals statewide. Middle-class students would now enjoy benefits previously reserved for the poor. But the kids quickly spotted a catch: the quality of food available in many schools has been greatly reduced.

The decline in food quality is just one of several unintended consequences. Others include worsening kids’ diets, increasing obesity, costing parents more time and money, and further burdening taxpayers. What began as targeted aid for the poor has morphed into a middle-class entitlement, entrenching a government-first model of social policy that prizes the appearance of equality over genuine improvements in child welfare.

In 2024, 90,000 schools received a total of $17 billion in federal aid from the National School Lunch Program (NSLP). The program provided up to $4.69 per meal for schools to deliver free and 40-cent lunches to 21 million of the nation’s 53 million schoolchildren. Schools can claim an additional $0.59 for feeding each of 8 million children who opt to purchase school-made lunches at uncapped prices.

Traditionally, eligibility for heavily subsidized meals was limited to children from households with incomes below 185 percent of the federal poverty level (currently $59,477 for a household of four) or those entitled to other federal welfare benefits. But the federal Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 created the Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), which allows schools to claim full federal subsidies for providing free lunches to wealthier students if their proportion of eligible low-income pupils qualifies.

CEP gives states an incentive to reduce the number of schoolchildren paying for lunch so that they can capture the full $4.69 per meal in federal subsidies. Eager to draw on expanded federal funding through the CEP, nine states now require schools to provide free meals to all students. The expanded access to subsidies eliminates any incentive for schools to spend more than the $4.69 per meal limit.

A press release issued by Governor Hochul boasts that the new policy “will reduce hunger among schoolchildren, spare parents both time and money, and simplify administration for schools.” It further claims that “academic performance increases and behavioral issues decrease when every child is assured of a nutritious meal.”

Left-leaning scholars have long argued that governments must make social services freely available to all residents to ensure that no one falls through the cracks of the system. Advocates point to bureaucratic hurdles that make it hard for kids to claim free lunches, note that many “food insecure” individuals have incomes above the traditional eligibility cut-off for free school meals, and suggest that welfare stigma may lead poor kids to go without school food to which they are entitled.

A recent review of research studies found moderate evidence that universal free meals boosted participation in school lunches and weaker evidence that it improved education attendance. The review also noted that little reporting existed on important outcomes relating to effects on diet and hunger. Some studies have linked expansions of CEP with measurable improvements in student discipline and educational outcomes. These results may owe to better nutrition; or perhaps access to free meals rewards good student behavior.

The benefit of expanding eligibility for free school lunches is largely limited to the nearly poor and could have been achieved by slightly broadening means tests. CEP funding was distributed to schools according to the proportion of their students eligible for federal welfare benefits, so it mostly served to bring universal meals to schools in poor communities. When free school meals were expanded to all during the pandemic, the reduction in “food insufficiency” was concentrated among the 14 percent of households with incomes between 185 percent and 250 percent of the federal poverty level; no significant reduction occurred among households with incomes above the median.

Universalizing free school meals is poorly targeted at filling nutrition gaps. It mostly serves to purchase lunch for those who can already afford it.

From 2014 to 2023, the proportion of schools providing free lunches to all students increased from 14 percent to 60 percent. Over that period, the share of American children in the lowest household income quartile who received free or reduced school lunches rose only from 92 percent to 94 percent, while the proportion in the highest income quartile getting free meals surged from 11 percent to 42 percent. The proportion of children who skipped meals remained unchanged at 0.8 percent, while the proportion of children “not eating enough” barely declined, from 4.2 percent to 4.1 percent.

As taxpayers pick up the tab for those previously willing to pay, school lunch budgets get squeezed. New York City’s budget office estimates that the federal subsidy covers only 73 percent of the cost of each free lunch. CEP’s growth eliminated private payments for lunches while increasing the volume of food consumed. Revenues per meal declined by 18 cents, leading schools to cut spending by 25 cents per meal. This has led to a drop in the quality of food made in schools, which had already suffered because of inflation and the rising cost of benefits for employees. (Food itself accounts for only 29 percent of the cost of the school lunch program; 54 percent goes to labor.)

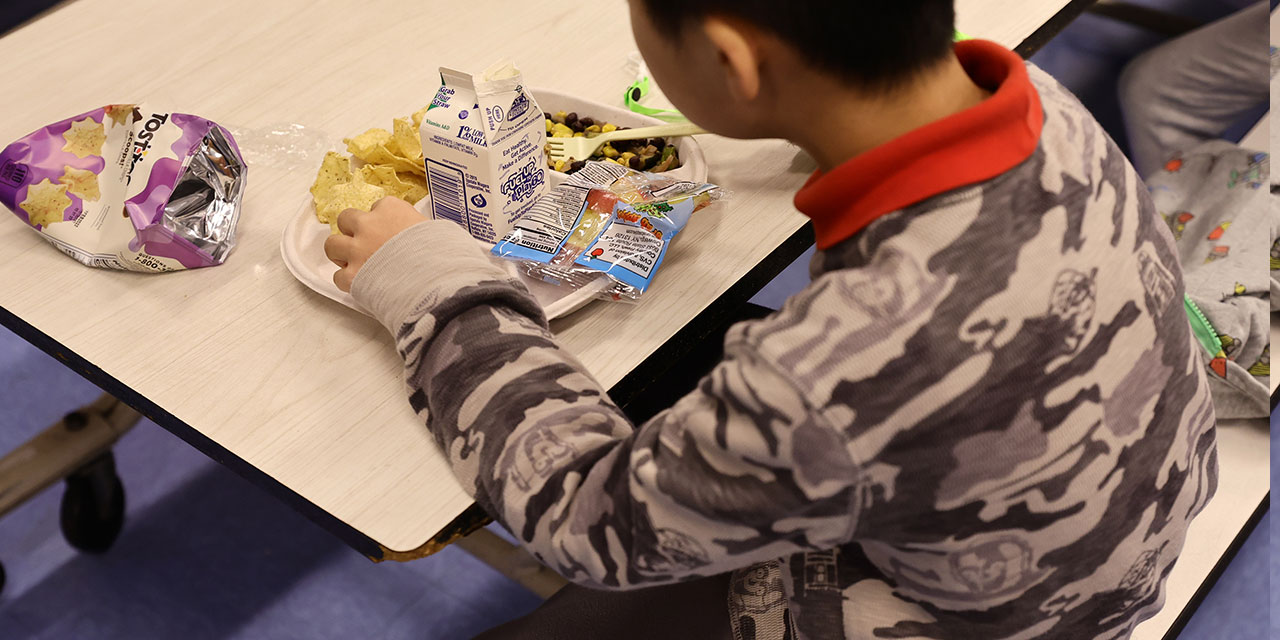

New York schools that switched to universal free meals this year have eliminated options for students, cut fresh items from the menu, and switched to frozen or packaged foods with artificial preservatives. Schools already highly dependent on public funds have long been familiar with such arrangements. In 2023, only 17 percent of schools nationwide offered food made from scratch every day, while only 3 percent exclusively served freshly made food.

When the quality of school food deteriorates, more parents switch their kids to bagged lunches, which costs them time and money. The proportion of students bringing lunch from home has risen over recent decades, despite rising maternal labor force participation and the vast expansion of free, school-made meals.

According to a recent Deloitte survey, 42 percent of parents make and pack lunch—though it costs them more than twice as much as school-made food. Seven out of ten parents said lunch brought from home provided better nutrition, 63 percent that it offered better value for money, and 52 percent that it provided more variety. Sixty-eight percent said their kids were more likely to eat, and less likely to waste, food brought from home.

Modern America’s main nutrition problem is not hunger but the quality of diets—something the expansion of free school lunches has done little to improve. A Department of Agriculture study comparing NSLP participants with similar nonparticipants found little difference in the proportion of each group eating excessive saturated fat or not enough key vitamins and fruits and vegetables. Though school meals improve the quality of diets consumed by children from low-income households, they worsen nutrition among kids from households above the median—the bulk of those made eligible by the universalization of free school lunch.

When kids can choose between home-prepared and free school food, they often opt for the less healthy option—and in many cases eat both, according to a study of the CEP. The study found increased obesity rates and a reduced probability of children having a healthy weight. From 2010 to 2018, the share of American children consuming vegetables on a given day declined slightly, from 92 percent to 90 percent; the child obesity rate rose from 17 percent to 22 percent between 2014 and 2023.

Contrary to the hopes of advocates, universal free meals will also likely worsen the stigma of consuming school-made food, as deteriorating quality causes middle-class parents increasingly to send in homemade or externally prepared food. Some kids bringing sushi from Whole Foods while others eat soggy cafeteria breadsticks would make lunch arrangements an even more visible signal of poverty in peer groups.

The push for universal free school meals does not exist in isolation. Like Medicare For All, it is part of a broader attempt to make the government the sole purchaser of goods for all social classes rather than just a source of assistance to those who can’t provide for themselves. In theory, such universal benefits make society more equal. In practice, the approach needlessly stretches scarce public funds, crowds out private resources, and degrades quality for everyone.

Photo by Michael Loccisano/Getty Images