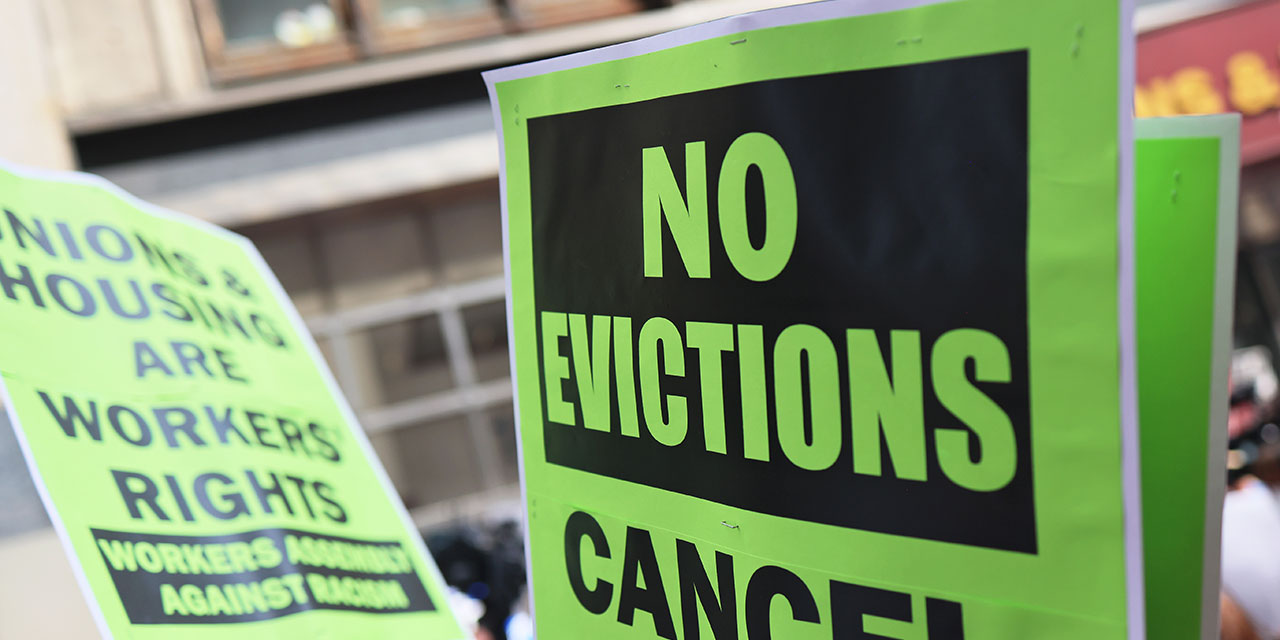

In recent years, states and cities have passed a slew of laws designed to protect renters. It is now harder than ever for landlords to pick the types of tenants they want and to remove them if they are causing trouble. Politicians have assumed such laws will keep families inside their homes while imposing minimal cost on others.

Yet a recent research paper shows that tenant-protection laws tend to drive up rents and likely hurt tenants far more than they help them. By increasing costs and risks for landlords renting in precarious urban markets, the laws end up hurting low-income renters most of all.

The study’s authors, Daniel Shoag and Issi Romem of the research firm Metrosight, examined cities with and without three kinds of tenant-protection laws: those that made evictions more difficult, those that restricted landlords from screening tenants for a criminal background or other issues, and those that required landlords to accept tenants with government housing vouchers. They compared places that had recently adopted such laws with those that had not and analyzed what happened to rents in each case.

The study finds that all types of tenant-protection laws led to higher rents. Laws that made it harder to evict tenants raised rents by an average of about $1,200 a year—roughly a 6 percent increase. Laws banning background screenings had a smaller but still notable effect, adding a few hundred dollars a year, or about 3 percent.

More striking were laws requiring landlords to accept government housing vouchers—known as Source of Income (SOI) discrimination laws. Though they receive less attention and directly affect fewer renters, SOI laws raised overall rents by about $1,000 a year, just over 5 percent.

These renter protections hit low-income households hardest. As expected, SOI laws had virtually no effect on high-earning renters, who don’t use vouchers. But they increased rents for the lowest-earning quarter of renters by nearly 6 percent. In practice, this meant that the vast majority of non-voucher tenants had to pay higher rents to offset the added costs landlords faced when renting to the small number of voucher holders, who often bring greater challenges and bureaucratic requirements. Anti-eviction laws showed a similarly disproportionate effect on low-income renters.

The report received funding from the National Apartment Association and the National Multifamily Housing Council, both of which represent landlords. Such funding should always raise eyebrows among readers. But it’s hard to dismiss the authors’ careful use of statistics or efforts to find alternative explanations for the rent increases besides the tenancy laws. No other explanation seems plausible, given the evidence.

The report also jibes with what we know from other research on tenant protections. A 2022 paper found that greater tenant protections tended to reduce eviction, as one would expect, but also led to higher rents and more homelessness. A paper last year found that right-to-counsel laws, which provide free legal assistance to tenants in eviction cases, raised listed rent prices by more than $300 per year in New York City. As I detailed in a report on SOI laws last year, the laws’ burdens on landlords have been substantial, while their benefits remain largely speculative.

More researchers are looking at tenant-protection laws because these measures are enjoying a sort of renaissance. In 2019, California imposed new, stringent “just cause” eviction standards, which meant certain landlords could evict tenants only for state-approved reasons. New York passed a similar law last year. During the pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention banned evictions nationwide under the specious pretext of public health; the Supreme Court eventually struck down the ban, but some cities and states kept eviction bans in place for years.

The tenant-protection campaign was never based on evidence, but instead on the vague suspicion that bad landlords were behind America’s urban ills. One hopes that with clearer proof of the costs of these laws, some proponents will have second thoughts.

Photo by Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images

City Journal is a publication of the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), a leading free-market think tank. Are you interested in supporting the magazine? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and City Journal are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).